Keywords: New Years

Item 20342

Swedish Baptist Church of New Sweden, ca. 1938

Contributed by: New Sweden Historical Society Date: circa 1938 Location: New Sweden Media: Photographic print

Item 20347

New Sweden Gustaf Adolph Lutheran Church, ca. 1938

Contributed by: New Sweden Historical Society Date: circa 1938 Location: New Sweden Media: Photographic print

Item 151334

Poland Springs House, Poland, 1891

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1891 Location: Poland Client: unknown Architect: John Calvin Stevens

Item 151603

Church of the New Jerusalem, Portland, 1908-1945

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1908–1945 Location: Portland; Portland Client: unknown Architect: John Calvin Stevens and John Howard Stevens Architects

Exhibit

Toy Len Goon: Mother of the Year

Toy Len Goon of Portland, an immigrant from China, was a widow with six children when she was selected in 1952 as America's Mother of the Year.

Exhibit

Immigration is one of the most debated topics in Maine. Controversy aside, immigration is also America's oldest tradition, and along with religious tolerance, what our nation was built upon. Since the first people--the Wabanaki--permitted Europeans to settle in the land now known as Maine, we have been a state of immigrants.

Site Page

New Portland: Bridging the Past to the Future - East New Portland Village Schools

"East New Portland Central High School X The original Central High School was built in 1921, as the product of over a year's worth of town vote…"

Site Page

New Portland: Bridging the Past to the Future - New Portland: Bridging the Past to the Future

"Two churches were also built in 1838; the Free Will Baptist Church and the Universalist Church. North New Portland saw the creation of the…"

Story

30 years of business in Maine

by Raj & Bina Sharma

30 years of business, raising a family, & showcasing our culture in Maine

Story

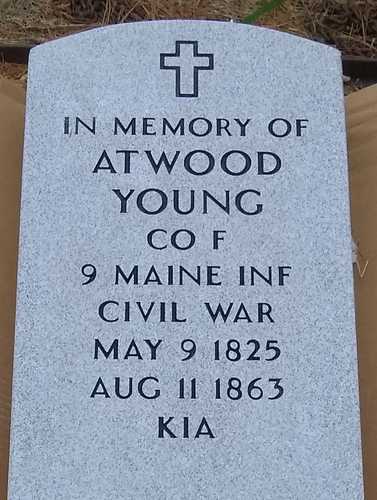

Civil War Soldier comes home after 158 years

by Jamison McAlister

Civil War Soldier comes home after 158 years

Lesson Plan

Becoming Maine: The District of Maine's Coastal Economy

Grade Level: 3-5

Content Area: Social Studies

This lesson plan will introduce students to the maritime economy of Maine prior to statehood and to the Coasting Law that impacted the separation debate. Students will examine primary documents, take part in an activity that will put the Coasting Law in the context of late 18th century – early 19th century New England, and learn about how the Embargo Act of 1807 affected Maine in the decades leading to statehood.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: "The Jewish Cemetery at Newport"

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Longfellow's poem "The Jewish Cemetery at Newport" opens up the issue of the earliest history of the Jews in America, and the significant roles they played as businessmen and later benefactors to the greater community. The history of the building itself is notable in terms of early American architecture, its having been designed, apparently gratis, by the most noted architect of the day. Furthermore, the poem traces the history of Newport as kind of a microcosm of New England commercial cities before the industrialization boom. For almost any age student the poem could be used to open up interest in local cemeteries, which are almost always a wealth of curiousities and history. Longfellow and his friends enjoyed exploring cemeteries, and today our little local cemeteries can be used to teach little local histories and parts of the big picture as well.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow visited the Jewish cemetery in Newport, RI on July 9, 1852. His popular poem about the site, published two years later, was certainly a sympathetic portrayal of the place and its people. In addition to Victorian romantic musings about the "Hebrews in their graves," Longfellow includes in this poem references to the historic persecution of the Jews, as well as very specific references to their religious practices.

Since the cemetery and the nearby synagogue were restored and protected with an infusion of funding just a couple years after Longfellow's visit, and later a congregation again assembled, his gloomy predictions about the place proved false (never mind the conclusion of the poem, "And the dead nations never rise again!"). Nevertheless, it is a fascinating poem, and an interesting window into the history of the nation's oldest extant synagogue.