Keywords: New York City

Item 35969

William Curtis Pierce, New York, ca. 1925

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: circa 1925 Location: New York; West Baldwin Media: Photographic print

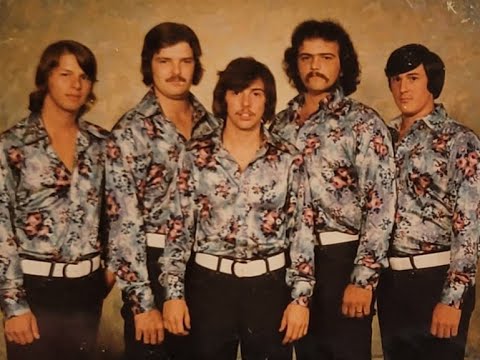

Item 70171

Royal Lace Paper workers, Brooklyn, New York, ca. 1951

Contributed by: Maine Folklife Center, Univ. of Maine Date: circa 1951 Location: Brooklyn Media: Photographic print

Item 87300

Assessor's Record, 30-38 York Street, Portland, 1924

Owner in 1924: New England Cold Storage Company Use: Storage

Item 37293

121-125 Commercial Street, Portland, 1924

Owner in 1924: John J Devine Use: Store & Storage

Item 151838

Butler Capital Corporation office, New York, New York, 1988

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1988 Location: New York Clients: Gilbert Butler; Butler Capital Corporation Architect: Patrick Chasse; Landscape Design Associates

Item 151858

Leon Levy Foundation, New York, New York, 2006

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 2006 Location: New York Clients: Leon Levy; Leon Levy Foundation Architect: Patrick Chasse; Landscape Design Associates

Exhibit

A City Awakes: Arts and Artisans of Early 19th Century Portland

Portland's growth from 1786 to 1860 spawned a unique social and cultural environment and fostered artistic opportunity and creative expression in a broad range of the arts, which flowered with the increasing wealth and opportunity in the city.

Exhibit

Immigration is one of the most debated topics in Maine. Controversy aside, immigration is also America's oldest tradition, and along with religious tolerance, what our nation was built upon. Since the first people--the Wabanaki--permitted Europeans to settle in the land now known as Maine, we have been a state of immigrants.

Site Page

View collections, facts, and contact information for this Contributing Partner.

Site Page

View collections, facts, and contact information for this Contributing Partner.

Story

Don Bisson - Living his convictions

by Biddeford Cultural & Heritage Center Voices of Biddeford project

Returning after a career in New York City, Don has dedicated his life to addressing food insecurity.

Story

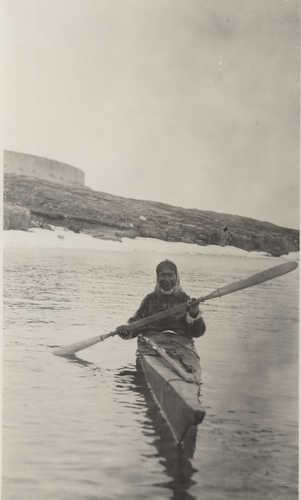

Minik Wallace 1891-1918

by Genevieve LeMoine, The Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum

The life of Minik, an Inuit person from Greenland who grew up in New York City.

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Most if not all of us have or will need to work in the American marketplace for at least six decades of our lives. There's a saying that I remember a superintendent telling a group of graduating high-school seniors: remember, when you are on your deathbed, you will not be saying that you wish you had spent more time "at the office." But Americans do spend a lot more time working each year than nearly any other people on the planet. By the end of our careers, many of us will have spent more time with our co-workers than with our families.

Already in the 21st century, much has been written about the "Wal-Martization" of the American workplace, about how, despite rocketing profits, corporations such as Wal-Mart overwork and underpay their employees, how workers' wages have remained stagnant since the 1970s, while the costs of college education and health insurance have risen out of reach for many citizens. It's become a cliché to say that the gap between the "haves" and the "have nots" is widening to an alarming degree. In his book Wealth and Democracy, Kevin Phillips says we are dangerously close to becoming a plutocracy in which one dollar equals one vote.

Such clashes between employers and employees, and between our rhetoric of equality of opportunity and the reality of our working lives, are not new in America. With the onset of the industrial revolution in the first half of the nineteenth century, many workers were displaced from their traditional means of employment, as the country shifted from a farm-based, agrarian economy toward an urban, manufacturing-centered one. In cities such as New York, groups of "workingmen" (early manifestations of unions) protested, sometimes violently, unsatisfactory labor conditions. Labor unions remain a controversial political presence in America today.

Longfellow and Whitman both wrote with sympathy about the American worker, although their respective portraits are strikingly different, and worth juxtaposing. Longfellow's poem "The Village Blacksmith" is one of his most famous and beloved visions: in this poem, one blacksmith epitomizes characteristics and values which many of Longfellow's readers, then and now, revere as "American" traits. Whitman's canto (a section of a long poem) 15 from "Song of Myself," however, presents many different "identities" of the American worker, representing the entire social spectrum, from the crew of a fish smack to the president (I must add that Whitman's entire "Song of Myself" is actually 52 cantos in length).

I do not pretend to offer these single texts as all-encompassing of the respective poets' ideas about workers, but these poems offer a starting place for comparison and contrast. We know that Longfellow was the most popular American poet of the nineteenth century, just as we know that Whitman came to be one of the most controversial. Read more widely in the work of both poets and decide for yourselves which poet speaks to you more meaningfully and why.