Keywords: artist

Item 12373

Mary Lane McMillan, Rome, 1933

Contributed by: Hollingsworth Fine Arts Date: circa 1933 Location: Rome; Belgrade Lakes Media: Printed black and white photo in original brochure

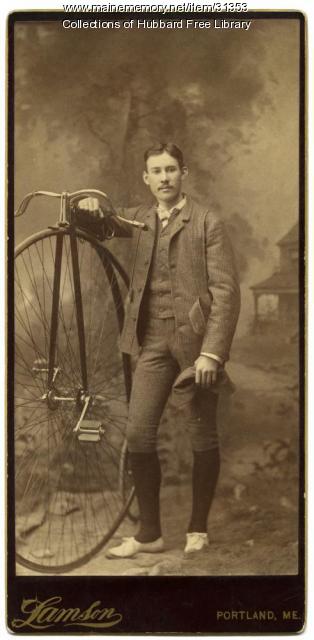

Item 31353

Alger V. Currier, artist, Hallowell, ca. 1890

Contributed by: Hubbard Free Library Date: circa 1890 Location: Hallowell Media: Photographic print

Item 151388

Moulton residence, Falmouth, 2008-2009

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 2008–2009 Location: Falmouth Client: Bessie Moulton Architect: Carol A. Wilson; Carol A. Wilson Architect

Item 151474

Patterson studio, Cape Elizabeth, 1925

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1925 Location: Cape Elizabeth Client: C. R. Patterson Architect: John Calvin Stevens and John Howard Stevens Architects

Exhibit

Capturing Arts and Artists in the 1930s

Emmie Bailey Whitney of the Lewiston Journal Saturday Magazine and her husband, noted amateur photographer G. Herbert Whitney, captured in words and photographs the richness of Maine's arts scene during the Great Depression.

Exhibit

A City Awakes: Arts and Artisans of Early 19th Century Portland

Portland's growth from 1786 to 1860 spawned a unique social and cultural environment and fostered artistic opportunity and creative expression in a broad range of the arts, which flowered with the increasing wealth and opportunity in the city.

Site Page

Biddeford History & Heritage Project - Artists and Inventors of Biddeford

"Artists and Inventors of Biddeford Creativity has flourished throughout Biddeford's history. Particularly in the arts and technology, the folks in…"

Site Page

Mount Desert Island: Shaped by Nature - …next came the artists and rusticators.

"…next came the artists and rusticators. Thomas Cole’s View across Frenchman’s Bay from Mount Desert Island after a Squall, 1845. Oil on canvas."

Story

Scientist Turned Artist Making Art Out of Trash

by Ian Trask

Bowdoin College alum returns to midcoast Maine to make environmentally conscious artwork

Story

One View

by Karen Jelenfy

My life as an artist in Maine.

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: Social Studies, Visual & Performing Arts

When European settlers began coming to the wilderness of North America, they did not have a vision that included changing their lifestyle. The plan was to set up self-contained communities where their version of European life could be lived. In the introduction to The Crucible, Arthur Miller even goes as far as saying that the Puritans believed the American forest to be the last stronghold of Satan on this Earth. When Roger Chillingworth shows up in The Scarlet Letter's second chapter, he is welcomed away from life with "the heathen folk" and into "a land where iniquity is searched out, and punished in the sight of rulers and people." In fact, as history's proven, they believed that the continent could be changed to accommodate their interests. Whether their plans were enacted in the name of God, the King, or commerce and economics, the changes always included and still do to this day - the taming of the geographic, human, and animal environments that were here beforehand.

It seems that this has always been an issue that polarizes people. Some believe that the landscape should be left intact as much as possible while others believe that the world will inevitably move on in the name of progress for the benefit of mankind. In F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby a book which many feel is one of the best portrayals of our American reality - the narrator, Nick Carraway, looks upon this progress with cynicism when he ends his narrative by pondering the transformation of "the fresh green breast of a new world" that the initial settlers found on the shores of the continent into a modern society that unsettlingly reminds him of something out of a "night scene by El Greco."

Philosophically, the notions of progress, civilization, and scientific advancement are not only entirely subjective, but also rest upon the belief that things are not acceptable as they are. Europeans came here hoping for a better life, and it doesn't seem like we've stopped looking. Again, to quote Fitzgerald, it's the elusive green light and the "orgiastic future" that we've always hoped to find. Our problem has always been our stoic belief system. We cannot seem to find peace in the world either as we've found it or as someone else may have envisioned it. As an example, in Miller's The Crucible, his Judge Danforth says that: "You're either for this court or against this court." He will not allow for alternative perspectives. George W. Bush, in 2002, said that: "You're either for us or against us. There is no middle ground in the war on terror." The frontier -- be it a wilderness of physical, religious, or political nature -- has always frightened Americans.

As it's portrayed in the following bits of literature and artwork, the frontier is a doomed place waiting for white, cultured, Europeans to "fix" it. Anything outside of their society is not just different, but unacceptable. The lesson plan included will introduce a few examples of 19th century portrayal of the American forest as a wilderness that people feel needs to be hesitantly looked upon. Fortunately, though, the forest seems to turn no one away. Nature likes all of its creatures, whether or not the favor is returned.

While I am not providing actual activities and daily plans, the following information can serve as a rather detailed explanation of things which can combine in any fashion you'd like as a group of lessons.

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 3-5, 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: Social Studies, Visual & Performing Arts

"In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?" Englishman Sydney Smith's 1820 sneer irked Americans, especially writers such as Irving, Cooper, Hawthorne, and Maine's John Neal, until Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's resounding popularity successfully rebuffed the question. The Bowdoin educated Portland native became the America's first superstar poet, paradoxically loved especially in Britain, even memorialized at Westminster Abbey. He achieved international celebrity with about forty books or translations to his credit between 1830 and 1884, and, like superstars today, his public craved pictures of him. His publishers consequently commissioned Longfellow's portrait more often than his family, and he sat for dozens of original paintings, drawings, and photos during his lifetime, as well as sculptures. Engravers and lithographers printed replicas of the originals as book frontispiece, as illustrations for magazine or newspaper articles, and as post cards or "cabinet" cards handed out to admirers, often autographed. After the poet's death, illustrators continued commercial production of his image for new editions of his writings and coloring books or games such as "Authors," and sculptors commemorated him with busts in Longfellow Schools or full-length figures in town squares. On the simple basis of quantity, the number of reproductions of the Maine native's image arguably marks him as the country's best-known nineteenth century writer. TEACHERS can use this presentation to discuss these themes in art, history, English, or humanities classes, or to lead into the following LESSON PLANS. The plans aim for any 9-12 high school studio art class, but they can also be used in any humanities course, such as literature or history. They can be adapted readily for grades 3-8 as well by modifying instructional language, evaluation rubrics, and targeted Maine Learning Results and by selecting materials for appropriate age level.