Keywords: city office

Item 7395

Old City Building, Lewiston, ca. 1885

Contributed by: Lewiston Public Library Date: circa 1885 Location: Lewiston Media: Phototransparency

Item 7029

Contributed by: Lewiston Public Library Date: circa 1872 Location: Lewiston Media: Phototransparency

Item 86129

Office, Browns Wharf Office Building, Portland, 1924

Owner in 1924: F E Irwin Lumber Company Use: Office

Item 86858

Office, Portland Pier, Portland, 1924

Owner in 1924: Proprietors of Portland Pier Use: Office

Item 151190

Waterville Federal Building and Post Office, Waterville, 1974-1975

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1974–1975 Location: Waterville Client: City of Waterville Architect: Eaton W. Tarbell

Item 150402

Cemetery Office Building for the City of Bath, 1919

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1919 Location: Bath Client: City of Bath Architect: Harry S. Coombs

Exhibit

Post office clerks began collecting strong red, white, and blue string, rolling it onto a ball and passing it on to the next post office to express their support for the Union effort in the Civil War. Accompanying the ball was this paper scroll on which the clerks wrote messages and sometimes drew images.

Exhibit

Hermann Kotzschmar: Portland's Musical Genius

During the second half of the 19th century, "Hermann Kotzschmar" was a familiar household name in Portland. He spent 59 years in his adopted city as a teacher, choral conductor, concert artist, and church organist.

Site Page

"Josh Shaw "What if the post office never existed?" The postal service refers to the post offices and mailing."

Site Page

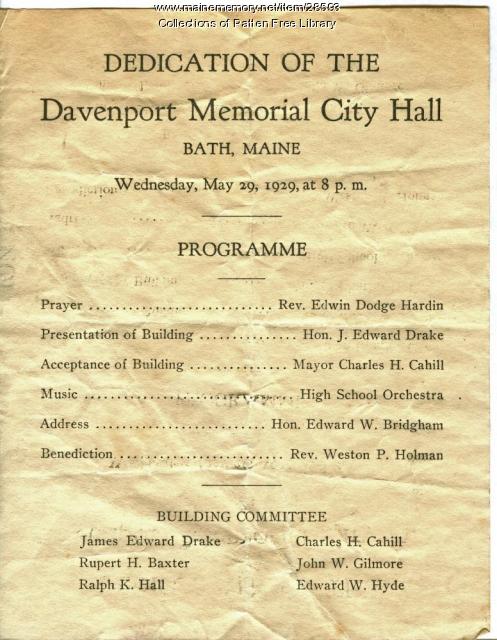

Bath's Historic Downtown - Davenport Memorial and City Hall

"It housed the offices of the city clerk, the treasurer, the mayor, and the police department. City Hall had a courtroom, a marshal's office, a…"

Story

Mike Remillard shares his in-depth knowledge of our community

by Biddeford Cultural & Heritage Center

You will learn a lot from Mike's fascination with many topics from church organs to submarines.

Story

Monument Square 1967

by C. Michael Lewis

The background story and research behind a commissioned painting of Monument Square.

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Most if not all of us have or will need to work in the American marketplace for at least six decades of our lives. There's a saying that I remember a superintendent telling a group of graduating high-school seniors: remember, when you are on your deathbed, you will not be saying that you wish you had spent more time "at the office." But Americans do spend a lot more time working each year than nearly any other people on the planet. By the end of our careers, many of us will have spent more time with our co-workers than with our families.

Already in the 21st century, much has been written about the "Wal-Martization" of the American workplace, about how, despite rocketing profits, corporations such as Wal-Mart overwork and underpay their employees, how workers' wages have remained stagnant since the 1970s, while the costs of college education and health insurance have risen out of reach for many citizens. It's become a cliché to say that the gap between the "haves" and the "have nots" is widening to an alarming degree. In his book Wealth and Democracy, Kevin Phillips says we are dangerously close to becoming a plutocracy in which one dollar equals one vote.

Such clashes between employers and employees, and between our rhetoric of equality of opportunity and the reality of our working lives, are not new in America. With the onset of the industrial revolution in the first half of the nineteenth century, many workers were displaced from their traditional means of employment, as the country shifted from a farm-based, agrarian economy toward an urban, manufacturing-centered one. In cities such as New York, groups of "workingmen" (early manifestations of unions) protested, sometimes violently, unsatisfactory labor conditions. Labor unions remain a controversial political presence in America today.

Longfellow and Whitman both wrote with sympathy about the American worker, although their respective portraits are strikingly different, and worth juxtaposing. Longfellow's poem "The Village Blacksmith" is one of his most famous and beloved visions: in this poem, one blacksmith epitomizes characteristics and values which many of Longfellow's readers, then and now, revere as "American" traits. Whitman's canto (a section of a long poem) 15 from "Song of Myself," however, presents many different "identities" of the American worker, representing the entire social spectrum, from the crew of a fish smack to the president (I must add that Whitman's entire "Song of Myself" is actually 52 cantos in length).

I do not pretend to offer these single texts as all-encompassing of the respective poets' ideas about workers, but these poems offer a starting place for comparison and contrast. We know that Longfellow was the most popular American poet of the nineteenth century, just as we know that Whitman came to be one of the most controversial. Read more widely in the work of both poets and decide for yourselves which poet speaks to you more meaningfully and why.