Keywords: Forge

- Historical Items (77)

- Tax Records (2)

- Architecture & Landscape (0)

- Online Exhibits (3)

- Site Pages (9)

- My Maine Stories (0)

- Lesson Plans (29)

Lesson Plans

Your results include these lesson plans. Your results include these lesson plans.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: Longfellow Meets German Radical Poet Ferdinand Freiligrath

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

During Longfellow's 1842 travels in Germany he made the acquaintance of the politically radical Ferdinand Freiligrath, one of the influential voices calling for social revolution in his country. It is suggested that this association with Freiligrath along with his return visit with Charles Dickens influenced Longfellow's slavery poems. This essay traces Longfellow's interest in the German poet, Freiligrath's development as a radical poetic voice, and Longfellow's subsequent visit with Charles Dickens. Samples of verse and prose are provided to illustrate each writer's social conscience.

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: Social Studies, Visual & Performing Arts

When European settlers began coming to the wilderness of North America, they did not have a vision that included changing their lifestyle. The plan was to set up self-contained communities where their version of European life could be lived. In the introduction to The Crucible, Arthur Miller even goes as far as saying that the Puritans believed the American forest to be the last stronghold of Satan on this Earth. When Roger Chillingworth shows up in The Scarlet Letter's second chapter, he is welcomed away from life with "the heathen folk" and into "a land where iniquity is searched out, and punished in the sight of rulers and people." In fact, as history's proven, they believed that the continent could be changed to accommodate their interests. Whether their plans were enacted in the name of God, the King, or commerce and economics, the changes always included and still do to this day - the taming of the geographic, human, and animal environments that were here beforehand.

It seems that this has always been an issue that polarizes people. Some believe that the landscape should be left intact as much as possible while others believe that the world will inevitably move on in the name of progress for the benefit of mankind. In F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby a book which many feel is one of the best portrayals of our American reality - the narrator, Nick Carraway, looks upon this progress with cynicism when he ends his narrative by pondering the transformation of "the fresh green breast of a new world" that the initial settlers found on the shores of the continent into a modern society that unsettlingly reminds him of something out of a "night scene by El Greco."

Philosophically, the notions of progress, civilization, and scientific advancement are not only entirely subjective, but also rest upon the belief that things are not acceptable as they are. Europeans came here hoping for a better life, and it doesn't seem like we've stopped looking. Again, to quote Fitzgerald, it's the elusive green light and the "orgiastic future" that we've always hoped to find. Our problem has always been our stoic belief system. We cannot seem to find peace in the world either as we've found it or as someone else may have envisioned it. As an example, in Miller's The Crucible, his Judge Danforth says that: "You're either for this court or against this court." He will not allow for alternative perspectives. George W. Bush, in 2002, said that: "You're either for us or against us. There is no middle ground in the war on terror." The frontier -- be it a wilderness of physical, religious, or political nature -- has always frightened Americans.

As it's portrayed in the following bits of literature and artwork, the frontier is a doomed place waiting for white, cultured, Europeans to "fix" it. Anything outside of their society is not just different, but unacceptable. The lesson plan included will introduce a few examples of 19th century portrayal of the American forest as a wilderness that people feel needs to be hesitantly looked upon. Fortunately, though, the forest seems to turn no one away. Nature likes all of its creatures, whether or not the favor is returned.

While I am not providing actual activities and daily plans, the following information can serve as a rather detailed explanation of things which can combine in any fashion you'd like as a group of lessons.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: Integration of Longfellow's Poetry into American Studies

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

We explored Longfellow's ability to express universality of human emotions/experiences while also looking at the patterns he articulated in history that are applicable well beyond his era. We attempted to link a number of Longfellow's poems with different eras in U.S. History and accompanying literature, so that the poems complemented the various units. With each poem, we want to explore the question: What is American identity?

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: Longfellow and Dickens - The Story of a Trans-Atlantic Friendship

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

What if you don't teach American Studies but you want to connect to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in meaningful ways? One important connection is Henry's friendship with Charles Dickens. There are many great resources about Dickens and if you teach his novels, you probably already know his biography and the chronology of his works. No listing for his association with Henry appears on most websites and few references will be found in texts. However, journals and diary entries and especially letters reveal a friendship that allowed their mutual respect to influence Henry's work.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: An American Studies Approach to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was truly a man of his time and of his nation; this native of Portland, Maine and graduate of Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine became an American icon. Lines from his poems intersperse our daily speech and the characters of his long narrative poems have become part of American myth. Longfellow's fame was international; scholars, politicians, heads-of-state and everyday people read and memorized his poems. Our goal is to show that just as Longfellow reacted to and participated in his times, so his poetry participated in shaping and defining American culture and literature.

The following unit plan introduces and demonstrates an American Studies approach to the life and work of Longfellow. Because the collaborative work that forms the basis for this unit was partially responsible for leading the two of us to complete the American & New England Studies Masters program at University of Southern Maine, we returned there for a working definition of "American Studies approach" as it applies to the grade level classroom. Joe Conforti, who was director at the time we both went through the program, offered some useful clarifying comments and explanation. He reminded us that such a focus provides a holistic approach to the life and work of an author. It sets a work of literature in a broad cultural and historical context as well as in the context of the poet's life. The aim of an American Studies approach is to "broaden the context of a work to illuminate the American past" (Conforti) for your students.

We have found this approach to have multiple benefits at the classroom and research level. It brings the poems and the poet alive for students and connects with other curricular work, especially social studies. When linked with a Maine history unit, it helps to place Portland and Maine in an historical and cultural context. It also provides an inviting atmosphere for the in-depth study of the mechanics of Longfellow's poetry.

What follows is a set of lesson plans that form a unit of study. The biographical "anchor" that we have used for this unit is an out-of-print biography An American Bard: The story of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, by Ruth Langland Holberg, Thomas Y. Crowell & Company, c1963. Permission has been requested to make this work available as a downloadable file off this web page, but in the meantime, used copies are readily and cheaply available from various vendors. The poem we have chosen to demonstrate our approach is "Paul Revere's Ride." The worksheets were developed by Judy Donahue, the explanatory essays researched and written by the two of us, and our sources are cited below. We have also included a list of helpful links. When possible we have included helpful material in text format, or have supplied site links. Our complete unit includes other Longfellow poems with the same approach, but in the interest of time and space, they are not included. Please feel free to contact us with questions and comments.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: Longfellow and the American Sonnet

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Traditionally the Petrarchan sonnet as used by Francesco Petrarch was a 14 line lyric poem using a pattern of hendecasyllables and a strict end-line rhyme scheme; the first twelve lines followed one pattern and the last two lines another. The last two lines were the "volta" or "turn" in the poem. When the sonnet came to the United States sometime after 1775, through the work of Colonel David Humphreys, Longfellow was one of the first to write widely in this form which he adapted to suit his tone. Since 1900 poets have modified and experimented with the traditional traits of the sonnet form.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow & Harriet Beecher Stowe

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: Social Studies

As a graduate of Bowdoin College and a longtime resident of Brunswick, I have a distinct interest in Longfellow. Yet the history of Brunswick includes other famous writers as well, including Harriet Beecher Stowe. Although they did not reside in Brunswick contemporaneously, and Longfellow was already world-renowned before Stowe began her literary career, did these two notables have any interaction? More particularly, did Longfellow have any opinion of Stowe's work? If so, what was it?

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: "The Jewish Cemetery at Newport"

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Longfellow's poem "The Jewish Cemetery at Newport" opens up the issue of the earliest history of the Jews in America, and the significant roles they played as businessmen and later benefactors to the greater community. The history of the building itself is notable in terms of early American architecture, its having been designed, apparently gratis, by the most noted architect of the day. Furthermore, the poem traces the history of Newport as kind of a microcosm of New England commercial cities before the industrialization boom. For almost any age student the poem could be used to open up interest in local cemeteries, which are almost always a wealth of curiousities and history. Longfellow and his friends enjoyed exploring cemeteries, and today our little local cemeteries can be used to teach little local histories and parts of the big picture as well.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow visited the Jewish cemetery in Newport, RI on July 9, 1852. His popular poem about the site, published two years later, was certainly a sympathetic portrayal of the place and its people. In addition to Victorian romantic musings about the "Hebrews in their graves," Longfellow includes in this poem references to the historic persecution of the Jews, as well as very specific references to their religious practices.

Since the cemetery and the nearby synagogue were restored and protected with an infusion of funding just a couple years after Longfellow's visit, and later a congregation again assembled, his gloomy predictions about the place proved false (never mind the conclusion of the poem, "And the dead nations never rise again!"). Nevertheless, it is a fascinating poem, and an interesting window into the history of the nation's oldest extant synagogue.

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 3-5, 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: Social Studies, Visual & Performing Arts

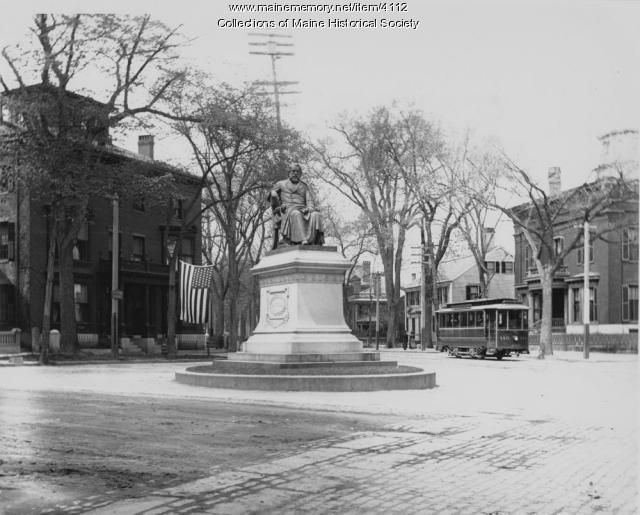

"In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?" Englishman Sydney Smith's 1820 sneer irked Americans, especially writers such as Irving, Cooper, Hawthorne, and Maine's John Neal, until Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's resounding popularity successfully rebuffed the question. The Bowdoin educated Portland native became the America's first superstar poet, paradoxically loved especially in Britain, even memorialized at Westminster Abbey. He achieved international celebrity with about forty books or translations to his credit between 1830 and 1884, and, like superstars today, his public craved pictures of him. His publishers consequently commissioned Longfellow's portrait more often than his family, and he sat for dozens of original paintings, drawings, and photos during his lifetime, as well as sculptures. Engravers and lithographers printed replicas of the originals as book frontispiece, as illustrations for magazine or newspaper articles, and as post cards or "cabinet" cards handed out to admirers, often autographed. After the poet's death, illustrators continued commercial production of his image for new editions of his writings and coloring books or games such as "Authors," and sculptors commemorated him with busts in Longfellow Schools or full-length figures in town squares. On the simple basis of quantity, the number of reproductions of the Maine native's image arguably marks him as the country's best-known nineteenth century writer. TEACHERS can use this presentation to discuss these themes in art, history, English, or humanities classes, or to lead into the following LESSON PLANS. The plans aim for any 9-12 high school studio art class, but they can also be used in any humanities course, such as literature or history. They can be adapted readily for grades 3-8 as well by modifying instructional language, evaluation rubrics, and targeted Maine Learning Results and by selecting materials for appropriate age level.

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Most if not all of us have or will need to work in the American marketplace for at least six decades of our lives. There's a saying that I remember a superintendent telling a group of graduating high-school seniors: remember, when you are on your deathbed, you will not be saying that you wish you had spent more time "at the office." But Americans do spend a lot more time working each year than nearly any other people on the planet. By the end of our careers, many of us will have spent more time with our co-workers than with our families.

Already in the 21st century, much has been written about the "Wal-Martization" of the American workplace, about how, despite rocketing profits, corporations such as Wal-Mart overwork and underpay their employees, how workers' wages have remained stagnant since the 1970s, while the costs of college education and health insurance have risen out of reach for many citizens. It's become a cliché to say that the gap between the "haves" and the "have nots" is widening to an alarming degree. In his book Wealth and Democracy, Kevin Phillips says we are dangerously close to becoming a plutocracy in which one dollar equals one vote.

Such clashes between employers and employees, and between our rhetoric of equality of opportunity and the reality of our working lives, are not new in America. With the onset of the industrial revolution in the first half of the nineteenth century, many workers were displaced from their traditional means of employment, as the country shifted from a farm-based, agrarian economy toward an urban, manufacturing-centered one. In cities such as New York, groups of "workingmen" (early manifestations of unions) protested, sometimes violently, unsatisfactory labor conditions. Labor unions remain a controversial political presence in America today.

Longfellow and Whitman both wrote with sympathy about the American worker, although their respective portraits are strikingly different, and worth juxtaposing. Longfellow's poem "The Village Blacksmith" is one of his most famous and beloved visions: in this poem, one blacksmith epitomizes characteristics and values which many of Longfellow's readers, then and now, revere as "American" traits. Whitman's canto (a section of a long poem) 15 from "Song of Myself," however, presents many different "identities" of the American worker, representing the entire social spectrum, from the crew of a fish smack to the president (I must add that Whitman's entire "Song of Myself" is actually 52 cantos in length).

I do not pretend to offer these single texts as all-encompassing of the respective poets' ideas about workers, but these poems offer a starting place for comparison and contrast. We know that Longfellow was the most popular American poet of the nineteenth century, just as we know that Whitman came to be one of the most controversial. Read more widely in the work of both poets and decide for yourselves which poet speaks to you more meaningfully and why.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: The Acadian Diaspora - Reading "Evangeline" as a Feminist and Metaphoric Text

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Evangeline, Longfellow's heroine, has long been read as a search for Evangeline's long-lost love, Gabrielle--separated by the British in 1755 at the time of the Grand Derangement, the Acadian Diaspora. The couple comes to find each other late in life and the story ends. Or does it?

Why does Longfellow choose to tell the story of this cultural group with a woman as the protagonist who is a member of a minority culture the Acadians? Does this say something about Longfellow's ability for understanding the misfortunes of others?

Who is Evangeline searching for? Is it Gabriel, or her long-lost land of Acadia? Does the couple represent that which is lost to them, the land of their birth and rebirth? These are some of the thoughts and ideas which permeate Longfellow's text, Evangeline, beyond the tale of two lovers lost to one another. As the documentary, Evangeline's Quest (see below) states: "The Acadians, the only people to celebrate their defeat." They, as a cultural group, are found in the poem and their story is told.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow's Ripple Effect: Journaling With the Poet - "The Song of Hiawatha"

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

This lesson is part of a series of six lesson plans that will give students the opportunity to become familiar with the works of Longfellow while reflecting upon how his works speak to their own experiences.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow's Ripple Effect: Journaling With the Poet - "My Lost Youth"

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12, Postsecondary

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

This lesson is part of a series of six lesson plans that will give students the opportunity to become familiar with the works of Longfellow while reflecting upon how his works speak to their own experiences.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow's Ripple Effect: Journaling With the Poet - "The Fire of Drift-Wood"

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12, Postsecondary

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

This lesson is part of a series of six lesson plans that will give students the opportunity to become familiar with the works of Longfellow while reflecting upon how his works speak to their own experiences.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow's Ripple Effect: Journaling With the Poet - "The Bridge"

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12, Postsecondary

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

This lesson is part of a series of six lesson plans that will give students the opportunity to become familiar with the works of Longfellow while reflecting upon how his works speak to their own experiences.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow's Ripple Effect: Journaling With the Poet - "Footsteps of Angels"

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12, Postsecondary

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

This lesson is part of a series of six lesson plans that will give students the opportunity to become familiar with the works of Longfellow while reflecting upon how his works speak to their own experiences.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow's Ripple Effect: Journaling With the Poet - "Psalm of Life"

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12, Postsecondary

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

This lesson is part of a series of six lesson plans that will give students the opportunity to become familiar with the works of Longfellow while reflecting upon how his works speak to their own experiences.

Lesson Plan

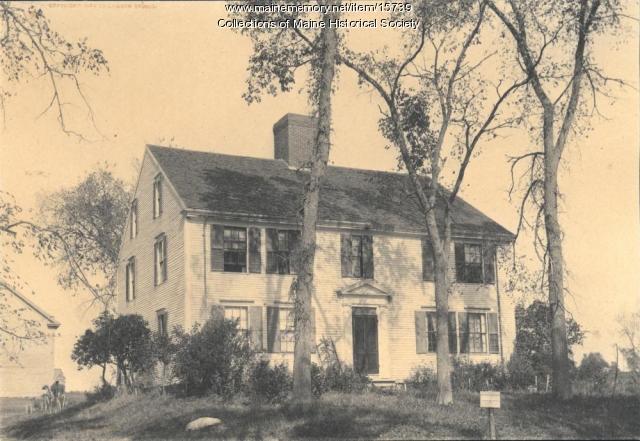

Longfellow Studies: The Elms - Stephen Longfellow's Gorham Farm

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

On April 3, 1761 Stephen Longfellow II signed the deed for the first 100 acre purchase of land that he would own in Gorham, Maine. His son Stephen III (Judge Longfellow) would build a home on that property which still stands to this day. Judge Longfellow would become one of the most prominent citizens in Gorhams history and one of the earliest influences on his grandson Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's work as a poet.

This exhibit examines why the Longfellows arrived in Gorham, Judge Longfellow's role in the history of the town, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's vacations in the country which may have influenced his greatest work, and the remains of the Longfellow estate still standing in Gorham today.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: "Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie"--Selected Lines and Illustrations

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: Social Studies, Visual & Performing Arts

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Maine's native son, is the epitome of Victorian Romanticism. Aroostook County is well acquainted with Longfellow's epic poem, Evangeline, because it is the story of the plight of the Acadians, who were deported from Acadie between 1755 and 1760. The descendants of these hard-working people inhabit much of Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

The students enjoy hearing the story and seeing the ink drawings. The illustrations are my interpretations. The collection took approximately two months to complete. The illustrations are presented in a Victorian-style folio, reminiscent of the family gathered in the parlor for a Sunday afternoon reading of Evangeline, which was published in 1847.

Preparation Required/Preliminary Discussion:

Have students read "Evangeline A Tale of Acadie". Give a background of the Acadia Diaspora.

Suggested Follow-up Activities:

Students could illustrate their own poems, as well as other Longfellow poems, such as: "Paul Revere's Ride," "The Village Blacksmith," or "The Children's Hour."

"Tales of the Wayside Inn" is a colonial Canterbury Tales. The guest of the inn each tell stories. Student could write or illustrate their own characters or stories.

Appropriate calligraphy assignments could include short poems and captions for their illustrations. Inks, pastels, watercolors, and colored pencils would be other appropriate illustrative media that could be applicable to other illustrated poems and stories. Each illustration in this exhibit was made in India ink on file folder paper. The dimensions, including the burgundy-colors mat, are 9" x 12". A friend made the calligraphy.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: The Exile of the People of Longfellow's "Evangeline"

Grade Level: 6-8

Content Area: Social Studies

Other materials needed:

- Copy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "Evangeline"

- Print media and Internet access for research

- Deportation Orders (may use primary document with a secondary source interpretation)

Throughout the course of history there have been many events in which great suffering was inflicted upon innocent people. The story of the Acadian expulsion is one such event. Britain and France, the two most powerful nations of Europe, were at war off and on throughout the 18th century. North America became a coveted prize for both warring nations. The French Acadians of present day Nova Scotia fell victim to great suffering. Even under an oath of allegiance to England, the Acadians were advised that their families were to be deported and their lands confiscated by the English. This event was immortalized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's epic poem "Evangeline", which was published in 1847.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: The Village Blacksmith - The Reality of a Poem

Grade Level: 6-8, 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

"The Village Blacksmith" was a much celebrated poem. Written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the poem appeared to celebrate the work ethic and mannerisms of a working man, the icon of every rural community, the Blacksmith. However, what was the poem really saying?

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: The Writer's Hour - "Footprints on the Sands of Time"

Grade Level: 3-5

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

These lessons will introduce the world-famous American writer and a selection of his work with a compelling historical fiction theme. Students take up the quest: Who was HWL and did his poetry leave footprints on the sands of time? They will "tour" his Cambridge home through young eyes, listen, and discuss poems from a writers viewpoint, and create their own poems inspired by Longfellow's works. The interdisciplinary approach utilizes critical thinking skills, living history, technology integration, maps, photos, books, and peer collaboration.

The mission is to get students keenly interested in what makes a great writer by using Longfellow as a historic role model. The lessons are designed for students at varying reading levels. Slow learners engage in living history with Alices fascinating search through the historic Craigie house, while gifted and talented students may dramatize the virtual tour as a monologue. Constant discovery and exciting presentations keep the magic in lessons. Remember that, "the youthful mind must be interested in order to be instructed." Students will build strong writing skills encouraging them to leave their own "footprints on the sands of time."

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: The Birth of An American Hero in "Paul Revere's Ride"

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

The period of American history just prior to the Civil War required a mythology that would celebrate the strength of the individual, while fostering a sense of Nationalism. Longfellow saw Nationalism as a driving force, particularly important during this period and set out in his poem, "Paul Revere's Ride" to arm the people with the necessary ideology to face the oncoming hardships. "Paul Revere's Ride" was perfectly suited for such an age and is responsible for embedding in the American consciousness a sense of the cultural identity that was born during this defining period in American History.

It is Longfellow's interpretation and not the actual event that became what Dana Gioia terms "a timeless emblem of American courage and independence."

Gioia credits the poem's perseverance to the ease of the poem's presentation and subject matter. "Paul Revere's Ride" takes a complicated historical incident embedded in the politics of Revolutionary America and retells it with narrative clarity, emotional power, and masterful pacing,"(2).

Although there have been several movements to debunk "Paul Revere's Ride," due to its lack of historical accuracy, the poem has remained very much alive in our national consciousness. Warren Harding, president during the fashionable reign of debunk criticism, perhaps said it best when he remarked, "An iconoclastic American said there never was a ride by Paul Revere. Somebody made the ride, and stirred the minutemen in the colonies to fight the battle of Lexington, which was the beginning of independence in the new Republic of America. I love the story of Paul Revere, whether he rode or not" (Fischer 337). Thus, "despite every well-intentioned effort to correct it historically, Revere's story is for all practical purposes the one Longfellow created for him," (Calhoun 261). It was what Paul Revere's Ride came to symbolize that was important, not the actual details of the ride itself.

Lesson Plan

Longfellow Studies: Longfellow Amongst His Contemporaries - The Ship of State DBQ

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Preparation Required/Preliminary Discussion:

Lesson plans should be done in the context of a course of study on American literature and/or history from the Revolution to the Civil War.

The ship of state is an ancient metaphor in the western world, especially among seafaring people, but this figure of speech assumed a more widespread and literal significance in the English colonies of the New World. From the middle of the 17th century, after all, until revolution broke out in 1775, the dominant system of governance in the colonies was the Navigation Acts. The primary responsibility of colonial governors, according to both Parliament and the Crown, was the enforcement of the laws of trade, and the governors themselves appointed naval officers to ensure that the various provisions and regulations of the Navigation Acts were executed. England, in other words, governed her American colonies as if they were merchant ships.

This metaphorical conception of the colonies as a naval enterprise not only survived the Revolution but also took on a deeper relevance following the construction of the Union. The United States of America had now become the ship of state, launched on July 4th 1776 and dedicated to the radical proposition that all men are created equal and endowed with certain unalienable rights. This proposition is examined and tested in any number of ways during the decades between the Revolution and the Civil War. Novelists and poets, as well as politicians and statesmen, questioned its viability: Whither goes the ship of state? Is there a safe harbor somewhere up ahead or is the vessel doomed to ruin and wreckage? Is she well built and sturdy or is there some essential flaw in her structural frame?