Text by Candace Kanes

Images from Maine Historical Society and Baldwin Historical Society

At first glance, Hannah Pierce (1788-1873) of Baldwin seems rather unremarkable – and not very happy.

While in her 20s, she taught school, one of the few occupations open to women in the early decades of the nineteenth century. After a few years, she returned to her parents' home, where she remained for the most of the rest of her life. As a single woman, she often helped care for sick relatives or those who needed help in various ways. In her later years, she repeatedly writes in letters that she is lonely and isolated.

Yet, Hannah Pierce, the eldest of 10 children of Josiah and Phebe Thompson Pierce of West Baldwin, was more remarkable than the brief description of her life suggests – and was far from the stereotype of an unhappy, bitter "old maid" (as she sometimes called herself).

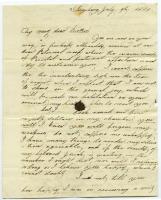

Hannah's letters, written between 1814 and 1866, mostly to her siblings, offer insight into how one single, independent woman in rural Maine negotiated family, intellectual pursuits, and finances.

Never particularly enamored of teaching, Hannah at 26, teaching in Fryeburg, wrote to her brother Josiah in 1814 that she had "upwards of forty Schollars, some of whom are wise, and some are otherwise even to an extreme." She could not understand the students' lack of academic ambition. She sometimes discussed books with Josiah or her other siblings in their correspondences and her letters suggest her interest in ideas and current events.

Hannah had benefited from her father's attitude that education was important for his daughters as well as his sons. Their education, like that of many youths of the time, came both at home and at academies, which they attended sporadically. Josiah "Squire" Pierce, among the first residents of Flintstown (later Baldwin), owned considerable property and was involved in mills, canals, lumbering and other pursuits. He sent two of his three sons on to study at Bowdoin College.

By 1817, Hannah wrote to her brother Josiah, "I am sick of school keeping and think if I can ever obtain any other employment by which to support myself I shall never engage in it again though I should not earn so much." That probably was the last year she taught.

Hannah went back to West Baldwin, traveling some to visit and assist various siblings and caring for her aging parents.

Before Josiah Pierce died in 1830, he wrote, "When my dear Wife & Hannah have done wanting this farm & these buildings – and a final settlement of my estate shall take place – it is my desire that one of my sons should own this farm & its buildings -- & keep the same if he shall be able."

However, he also wrote, in the same document, that he wanted Phebe and Hannah to stay on the farm "during their lives – unless my daughter Hannah should have a house of her own."

Hannah and her mother did remain together at the homestead until Phebe Pierce's death in 1839. By then, Josiah Pierce, the eldest son, owned a house in Gorham where he lived with his wife and seven children. The second son, Daniel, was not well settled, moving from job to job. He and his wife and family soon moved to Michigan. The youngest son, George, died in 1835. None of the sons was in a position to take over the house and farm and keep them operating.

When the estate was settled in April 1844, the land was divided equally among the siblings, even though their father had written, "It is my wish that this place may be kept together." Apparently, because Hannah was single and still living in the house, her share included the house.

Even then, Hannah was not alone. Daniel, who owned the strip of farmland immediately to the south of Hannah's land, and his family also occupied the house for a few years. A young neighbor, Lydia Jane Bachelder, moved in sometime before 1860 to help with household and farm chores (another neighborhood girl probably had lived with Hannah before that).

In addition, Hannah's niece, Phebe Elizabeth Sanborn and her young daughter, Nancy, also moved in sometime before 1860. Sanborn was a widow and lived with her aunt until Hannah Pierce's death in 1873.

While it was not common for property to pass to daughters when a family had sons to inherit, Josiah Pierce wanted his eldest child to have a home of her own and wanted all of his children to inherit equally,

In a substantial collection of letters between Hannah Pierce and her siblings, especially her brother Josiah of Gorham (1792-1866), Hannah writes about her finances, her increasing isolation as she ages, her health issues, concerns and problems in running the farm and finding people to farm the fields, and her "little family" – Lydia Jane, (Phebe) Elizabeth, and Nancy. Hannah had investments in real estate, banks, factories and other concerns. She often asked Josiah for advice and their relationship remained close.

She often refers to herself in a somewhat lighthearted manner as an "old maid." When she writes about being lonely, it is often winter when bad weather or illness has kept family and friends from visiting her and her from getting out to visit. Especially in her younger years, her letters exhibit good humor and enjoyment of life. Even in winter, she writes about being "happy and contented."

Hannah sought her brother's advice on hiring farmers and other questions related to her property, yet made many decisions herself – and often did some of the farm labor herself. In 1855, when she was 66, she planned to do the dairying herself. The next winter, she sold her pigs and sent her cows to a neighbor's. She and the "girls" had plenty of wood and water, but, she said, "I fear the great snows and long winter." She planned to spend part of the winter with Josiah and his family, while the "girls" went to Limerick where Elizabeth's father lived.

In January 1858, she wrote to Josiah about prospects for leasing the farm and noted, " I should indeed be very glad, of some money, as for the first time in my life, I am intirely destitute, of that article." By then, Josiah, a successful lawyer and judge, also was in financial straits.

But Hannah survived financially and outlived all but one of her siblings, Ruth Pierce Crocker (1794-1875). She continued to live on the farm until her death in 1873, earning money by leasing fields or taking a share of the farm profits from live-in farmers, by selling apples and hay, and by managing her investments.

She left various of her possessions – money, furniture, linens, clothing – to specific nieces, nephews, siblings, and the neighbor girl who had lived with her for so long. She left "all the remainder & residue of my property real & personal to the children of my brothers Josiah & Daniel T. Pierce & of my sisters Nancy P. Freeman & Sarah R. P. Gooch." The real property apparently included the house and land Hannah had lived on her whole life.

In a family in which many of the men achieved notice in politics, business and civic engagement, Hannah Pierce's life centered on family and homestead, but also stands out as a model of how a single woman could achieve independence, financial and business acuity, and engagement with others.

Many single women lived with siblings or other relatives as dependents in their households. Lonely and isolated as she aged, she strove to remember the blessings of her home, her health, and her independence.