Text by Steve Bromage, Executive Director of Maine Historical Society.

Images from Ambajejus Boom House Museum, Greater Rumford Area Historical Society, Lincoln Historical Society, Maine’s Paper and Heritage Museum, the Muskie Archives at Bates College, Norcross Heritage Trust, Penobscot Marine Museum, Tate House Museum, and Westport Island History Committee.

When Hugh Chisolm opened the Otis Falls Pulp Company in Jay in 1888, it was a watershed moment for Maine. The mill was one of the most modern papermaking facilities in the country, and was connected to national and global markets with a voracious appetite for paper. For the next century, Maine became an international leader in the manufacture of pulp and paper.

Paper has shaped Maine’s economy, provided livelihoods, molded individual and community identities, and impacted the environment—both positively and negatively— throughout the state.

2017 has brought a time of intense change in Maine’s economy and the paper industry, and the historic transition taking place in Maine’s paper industry. We seek to preserve the stories of the people and communities who have driven it, and to stimulate conversation about what comes next for Maine’s economy, communities and forests.

Trees

The paper and pulp industry thrived in Maine because of its millions of acres of forestland and proximity to markets. Maine's northern climate and geography—including a landscape shaped by cool temperatures, receding glaciers, and the rivers, lakes, and streams they left—created a climate where dense mixed hardwood and conifer trees have flourished.

Since the earliest Wabanaki settlements, trees have been a critical resource for the people who live in what is now known as Maine. Trees are used for fire, shelter, transportation, tools, and trade.

Wabanaki people invented the birch bark canoe, which sped travel and expanded cultural and trading circles. Later, Europeans set their sights on the tall, straight white pines which were coveted for use as ship masts.

During the first half of the 1800s, Maine lumber fed the growth of East Coast cities. 1872 was the peak production year for the lumber industry in Bangor, but by the end of the Civil War and with the country’s development moving west, demand for Maine lumber leveled off. With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad and the opening of the Northwest territories, investors in Maine sought new economic opportunities. These included manufacturing, tourism—and new uses for trees, including making paper.

Paper

Broadside seeking rags for paper making, Westbrook, 1795

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

Fiber is the essential element needed to make paper. For thousands of years, people made paper from fibers extracted from recycled cloth rags.

By the mid-1800s, America's rapid industrialization created an insatiable demand for paper. Soon the supply of rags couldn't keep up, and innovators began looking for alternative sources of fiber, like wood.

See more of Victor Keppler's photographs of Eastern Fine Paper

Victor Keppler was a commercial photographer from New York who produced advertisements for large companies such as General Electric, Corning Glass, and DuPont, and Eastern Fine Paper.

Colonels Thomas Westbrook and Samuel Waldo operated the first paper mill in Maine as early as 1734, located on the Presumpscot River in Westbrook. In 1854, Samuel D. Warren purchased the land tract and mill site, forming the S.D. Warren Company. Warren was one of the first entrepreneurs to add wood fibers to the fabric rags previously used as the base for paper.

Papermaking technology has evolved continually but still follows the same basic steps: 1) Remove the bark from logs or start with chipped wood; 2) Use heat or chemicals to "digest" the wood into a slurry of cellulose fibers, or pulp; 3) Clean the fibers; 4) Spray the fibers onto moving wire mesh where they mat together and become sheets; 5) Feed the sheets through heated rollers where they become paper; 6) Cut and sort paper sheets or rolls.

While demand for certain types of paper, like newsprint, has decreased in the digital age, others like cardboard packaging and tissue have increased. In 2017, paper industry researchers are developing new technologies for pulp and paper.

Economics

Maine mobilized to meet the world's vast demand for paper. Maine businesspeople, supported by investors from Boston and New York, surveyed the state’s geography, identified strategic sites, built state-of-the-art paper mills, connected the mills to rail lines and national markets, and helped establish the paper industry as a dominant force in Maine. Capital flooded into the state.

Paper companies industrialized the Maine woods. They began acquiring millions of acres of forestlands, and employed thousands of loggers who worked the forests owned and managed by the growing paper companies and other major landholders. Rivers provided transportation for logs, and were dammed to generate power to run mills. Water was an essential resource for processing and cleaning wood fibers, and disposing of waste. Entire towns were designed and built to support the massive new mills.

Learn more about the Pioneers in Paper Making from Jay & Livermore Falls

Otis Falls Pulp & Paper Mill, Livermore Falls, circa 1896

Courtesy of Maine's Paper and Heritage Museum

Item Contributed by

Maine's Paper & Heritage Museum

As the pulp and paper industry grew, it emerged as a powerful influence in the state legislature in Augusta and in commercial centers like Bangor and Portland.

Maine became an international leader in technologies related to paper. The industry employed foresters, engineers, scientists, hydrologists, accountants, woods workers, mill workers, boat captains and truckers, who were innovators and experts in each part of the operation. Many received training from the University of Maine.

Paper making at an industrial scale also required substantial infrastructure—including roads throughout Maine’s forests, dams, mills, rail lines, and ports. As recently as 2011, the forest products sector supported 38,789 direct and indirect jobs, or one out of every twenty jobs in Maine.

Community

Communities emerged and thrived around paper mills. The papermaking process was labor intensive and needed thousands of workers to keep up with international demand. Workers came to Maine's paper mill communities from around the world.

The town of Millinocket was designed specifically to support the mill that Great Northern Paper Company opened there in 1900. Millinocket, dubbed the “magic city in Maine’s wilderness” was laid out around the mill and its operations, including housing, support services, schools, and community centers.

The paper industry provided some of the best-paying jobs in Maine. A 1960 graduate of Stearns High School could expect to be hired immediately after graduation, and to earn an excellent salary until retirement. This livelihood provided economic security, pride in one's own role and contribution, and confidence in the future.

The industrialization of the Maine Woods created periodic labor strife and led to social, economic, and ethnic divisions. In many paper communities, the owners or management lived on one side of the river, workers on the other, and strikes in mill towns like Jay and Rumford drove deep divisions between workers and companies.

One of the most distinct features and legacies of Maine’s papermaking culture is “camp” life. Paper companies allowed public access and leased affordable camp lots on company-owned land to workers. Mill employees built cabins and spent free time hunting, fishing, canoeing, hiking, and snowmobiling.

Mill communities thrived throughout rural Maine. People built lives and created a uniquely Maine culture and identity. Dorothy Bowler Laverty, author of the book, Millinocket; Magic City of Maine’s Wilderness, amassed a collection of photographs that provide a glimpse into the routines of life in and around paper mill communities.

Environment

The paper industry’s impact on Maine's environment was transformative. To be competitive in the market, mill owners sought to maximize yields and returns as efficiently as possible.

Forests were cut. Iconic log drives impacted water quality and limited recreational use of portions of the Androscoggin, Kennebec, and Penobscot Rivers. Dams blocked the migration of fish, and paper companies controlled water. Industrial effluent flowed freely into the rivers and air.

The impact of the paper industry helped stimulate Maine's national leadership in the environmental movement. Mainers weren't squeamish about utilizing Maine's natural resources, but diverse constituents recognized that Maine's rivers and woods were among the state's greatest assets.

Private land owners and paper companies—whose livelihoods depended on cutting trees—instituted selective harvesting and other sustainable forest management practices. Federal regulations like the Clean Water Act of 1972 legislated guidelines for environmental protections, and advocates for Maine's recreational fishing industry helped fight to clean up rivers and remove dams.

Going Forward

By the 1970s, the structure of the global economy had shifted, and it became cheaper to make paper in other parts of the world.

Paper remains a capital and technology intensive industry, and sustainability requires decades of foresight, planning, and investment. For much of the industry’s existence, corporate ownership and decision-making happened outside of Maine—a common theme in Maine’s economic history. Aging infrastructure, high energy costs, competition, and a decreased demand for newsprint have all eroded Maine’s former competitive advantages.

Recently, mills have closed in Millinocket and East Millinocket (Great Northern Paper Company), Lincoln (Lincoln Paper & Tissue), Old Town (Old Town Fuel & Fiber), Bucksport (Verso), and Madison (UPM Madison). From 2011-2016, over 2300 jobs were lost in the mills. Related economic impact spreads to loggers, local businesses, and municipal governments.

Six major paper mills remain: in Madawaska (Twin Rivers Paper Company), Baileyville (Woodland Pulp LLC), Rumford (Catalyst Paper), Jay (Verso Paper Company), Skowhegan (SAPPI), and Westbrook (SAPPI).

Even with recent mill closures, the paper industry is far from disappearing in Maine. Maine continues to be one of the top producers of paper in the United States. The industry is transitioning to an era where science, technology, innovation, and investment are more important than ever. The future will require fewer workers and more training. Opportunities and reinvention will vary from community to community. For many individuals and towns, the future will not include papermaking.

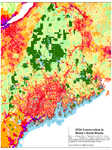

Maine’s North Woods are the largest undeveloped tract of forestlands east of the Rockies. These forestlands remain one of the most special and spectacular natural landscapes in the world, with the capacity to support robust economic activity—ranging from wood products, to recreation, to tourism.

Public lands, paper companies, conservation and innovation

Since the arrival of Europeans in Maine, large tracts of forestland have been held by relatively few entities, including Tribal Nations, state and federal agencies and paper companies.

The Forest Society of Maine, and other conservation organizations, the state, private landowners, industry, and others committed to the long-term vitality of the woods, have conserved more than three million acres of productive forestland in Maine, mostly since paper mills sold their land holdings beginning in 1998.

In January 2017, Our Katahdin, a non-profit organization based in the Katahdin region, acquired the former Great Northern Paper Company assets in Millinocket, including the 1,400-acre former mill site.

We know this purchase comes with enormous responsibility. We can’t promise instant results, but we can guarantee our best effort to help transform this idle industrial site into a productive, innovative bio- industrial park that leverages the comparative advantages of our region. This site is our heritage. We strongly believe in its future.

Sean Dewitt, President of Our Katahdin, January 12, 2017

Millinocket is diversifying its economy, in part, by becoming a gateway to the new Katahdin Woods & Waters National Monument. Other communities are investing in biomass plants, diversified forest products, and tourism.

Since 1995, SAPPI Fine Paper has owned mills in Maine including the former S.D. Warren site in Westbrook where paper has been made since the 1730s. SAPPI specializes in coated "release" paper, used to create products including patterned car interiors, flooring, shoes, and soccer balls.

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/exhibits/paper