Holding up the Sky was curated and advised by:

Lisa Brooks (Abenaki) Professor of English and American Studies, Amherst College, Massachusetts; James Eric Francis Sr. (Penobscot) Director of Cultural and Historic Preservation, Penobscot Nation; Suzanne Greenlaw (Maliseet) Ph.D student, University of Maine, Orono; Tilly Laskey, Curator, Maine Historical Society; Micah Pawling, Professor of History and Native American Studies, University of Maine, Orono; Darren Ranco (Penobscot), Professor of Anthropology and Coordinator of Native American Research, University of Maine, Orono; Theresa Secord (Penobscot), Artist and Maine Historical Society Trustee; Ashley Smith (Wabanaki descent), Assistant Professor of Native American Studies and Environmental Justice, Hampshire College, Massachusetts; Donald Soctomah (Passamaquoddy) Director, Passamaquoddy Cultural Heritage Center and Passamaquoddy Tribal Historic Preservation Officer.

On display at Maine Historical Society, 489 Congress Street, Portland, Maine from April 12, 2019-February 1, 2020

Please visit State of Mind: Becoming Maine, a companion exhibition examining Maine's Bicentennial.

What does it mean to be in one place for over 13,000 years?

Katahdin by James Eric Francis Sr. (Penobscot)

According to Penobscot oral histories, Glooscap, the first man, keeps his lodge at Katahdin, called ktàtən in the Penobscot language. The mountain is an important and sacred place. At 5,270 feet above sea level, Katahdin is the highest point in Maine. James Eric Francis took this image on November 15, 2014 during an aurora borealis and meteor shower event. Courtesy of the artist.

Wabanaki means People of the Dawnland. As the first people to greet the sunrise, they are responsible for “holding up the sky.”

Wabanaki people, including the Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Abenaki Nations, have inhabited what is now northern New England, the Canadian Maritimes, and Quebec, since time immemorial according to oral histories, and for at least 13,000 years according to the archaeological record.

Wabanakis are constantly adapting in response to dramatic changes in the environment. Their cultures also have changed over time, with the development of sophisticated political networks, evolving philosophies, and a deep understanding of the landscape.

For generations, Wabanaki people traveled seasonally, planting corn on the riverbanks in the spring, harvesting fish on the coast and gathering berries during the summer, and hunting game in the woods during wintertime. Their mobile lifestyle was prosperous, but radically changed with the coming of European settlers around 400 years ago, and later with the splitting of ancestral territory through the establishment of arbitrary international and state borders.

Archaeology

Glaciers covered Maine 15,000 years ago. As the climate warmed a tundra landscape and large game evolved, including wooly mammoths, mastodons, and saber-toothed cats. Between 9,000 and as many as 13,000 years ago, Paleo Indians—ancestors of the Wabanaki— followed the big game, hunting and living in what is now Maine.

Rivers developed from melting glaciers and forests grew as the environment stabilized. The Wabanaki adapted to the changing ecosystem, becoming expert stone and toolmakers, weaving baskets and snowshoes, and creating other cultural items that enabled successful hunting and fishing. Lifestyles were mobile, and people traveled and traded over long distances.

Kineo Rhyolite

Mount Kineo is located on Moosehead Lake. The mountain contains one of the largest formations of rhyolite (igneous rock that is the volcanic equivalent of granite) in the world. The Kineo Rhyolite is prized for being an extremely strong and durable stone, yet easily carved. For this reason, it was ideal for making projectile points and other tools.

Wabanaki oral histories re-count stories of Gluscabe, who created Mount Kineo by making an arrowhead out of a nearby stone and shooting it at a cow moose. The moose fell, and turned into that specific stone—Kineo Rhyolite—that is quarried at Mount Kineo and is the perfect tool for making projectile points.

When the inland sea covering Maine receded, it left a thick layer of marine clay—the Presumpscot Formation—perfect for forming pottery vessels. As populations grew, so did technology. Pottery making in Wabanaki communities began around 3000 years ago, making storing and cooking food much easier. This pot dates to about 2700 years ago and was found at Harlow's Point along the shoreline of Lake Auburn in 1881.

Wabanaki Diplomacy

About 500 years ago, Wabanakis first received Basque fishermen, Italian explorer Verrazano in 1524 though he noted they weren’t very friendly, French fur traders, and later, English colonists to their homeland.

For me, understanding and reading 17th and 18th century colonial documents through Wabanaki political and cultural frameworks is part of a process of ôjmowôgan, the Abenaki word for history. The language tells us that “history” is a collective process of telling and re-telling, an ongoing activity in which we are all engaged.

Penobscot author Joseph Nicolar recorded a tribal prophecy noting that elders, “decided, that when the strange people came, to receive them as friends, and if possible make brothers of them.” When English people arrived in Wabanaki territory, including the land now known as Maine, Wabanaki leaders worked to incorporate settlers into their social and ecological networks, to create responsible relationships, and to “make kin” and alliances with their guests.

English guests all too often misinterpreted such hospitality, misunderstanding the obligations that accompanied the privilege of sharing space. The written language of the English as compared with wampum protocols and verbal agreements of the Wabanaki led to confusion and to deliberate dispossession. Even as Wabanaki people strove to incorporate settlers into their Indigenous cultural and economic systems, the settlers sought their signatures and consent of land ownership on finite political documents.”

Lisa Brooks, Abenaki (Missisquoi and Pemigewasset)

Amherst College

Treaties

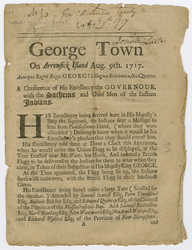

Conference at George Town and Arrowsick Island August 9, 1717

Collections of Maine Historical Society, Coll. 60 B13 F3

The Arrowsic Treaty (Conference at Georgetown) documents Wabanaki understandings of the ecological capacity and limits of their homeland, and Wabanaki leaders’ insistence on maintaining sovereignty in order to sustain that homeland. Wabanaki leaders, including Wiwurna, met with Governor Samuel Shute of Massachusetts Colony in August 1717 at Menaskek (Georgetown) on Arrowsic Island. The Wabanaki confronted the English about encroaching settlements and trading posts. Wiwurna insisted that English claims to lands on the Kennebec River and east of it were unfounded. He said the Wabanaki territory did not have the resources to adequately host the stream of settlers who were increasingly impacting their homeland.

• Wiwurna: “This Place was formerly Settled and is now Settling at our request: And we now return Thanks that the English are come to Settle here, and will Imbrace them in our Bosoms that come to Settle on our Lands.”

• Shute, interrupting: “They must not call it their Land, for the English have bought it of them and their Ancestors.”

• Wiwurna: “We Pray leave to proceed in our Answer, and talk that matter afterward. We desire there may be no further Settlements made. We shan't be able to hold them all in our Bosoms, and to take care to shelter them, if it be likely to be bad weather, and Mischief be Threatened."

The Wabanakis were willing to consent to existing English settlements if a proper boundary was delineated. Shute responded, "We desire only what is our own, and that we will have."

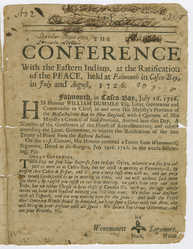

The Conference with the Eastern Indians, at the Ratification of the Peace in Falmouth, 1726

Collections of Maine Historical Society, Coll. 60 B13 F3

In 1727, the Penobscot speaker diplomat Loron (also known as Lolon Saguarrab) contested the authority of the printed words of this 1726 treaty, The Conference with the Eastern Indians, at the Ratification of the Peace in Falmouth, claiming it did not reflect the verbal exchange in council. Specifically, he objected to the assertion of English sovereignty over Wabanaki people and lands.

"We desire Brothers as we have so good an Understanding together that there be no other Houses built there, unless it be by purchase or Agreement, The Neighbouring Tribes have already told us that we should go on with the Treaty with good Understanding and Courage, and settle every thing, That if a Line should happen to be Run, the English may hereafter be apt to step over it, so that every thing they desire may be Settled Strong."

Loron pointed to the misrepresentation of his words in English print and the validity of his own language, insisting that,

"What I tell you now is the truth. If, then, anyone should produce any writing that makes me speak otherwise, pay no attention to it, for I know not what I am made to say in another language, but I know well what I say in my own. And in testimony that I say things as they are, I have signed the present minute which I wish to be authentic and to remain for ever."

Later, Loron asserted collective sovereignty and the Wabanaki practice of holding lands in common as he refuted the King of England’s authority over Wabanaki territory,

"He again said to me – But do you recognize the King of England as King of all his states? To which I answered – Yes, I recognize him King of all his lands; but I rejoined, do not hence infer that I acknowledge thy King as my King, and King of my lands. Here lies my distinction – my Indian distinction. God hath willed that I have no King, and that I be master of my lands in common."

English is the foreign language

Wabanaki languages are the first language of Maine. The original words of this land—Casco, Katahdin, Kennebec, Androscoggin, Pemaquid, moose—surround us.

Abenaki, Micmac, Maliseet/Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot languages are part of the Algonkian language group, and each Tribe has a distinct language that expresses worldview. The names they use to describe themselves are evocative of their place in Maine:

Mi’gmaw (Micmac) – my kin-friends

Panawahpskewtəkʷ (Penobscot) – river of white rocks opening or spreading out

Peskotomuhkatiyik (Passamaquoddy) – people who spear pollock

Wolastoqewi (Maliseet) – people of the beautiful river

As settlers colonized Maine with a dominant English language system, they named towns after their founding fathers or English homelands, resulting in a situation where Wabanaki people are now living in a deeply familiar place, populated with foreign words.

Wabanaki children were at times forcibly removed from their homes, and were not allowed to speak their languages. Tribal members left the reservations for educational and employment opportunities to cities like Portland and Boston, where they raised families. As a result, generations of Wabanaki people grew up not knowing their language. Language revitalization and school programs in Wabanaki communities have brought languages back from the brink of loss.

Sovereign Nations

The Wabanaki have maintained a nation-to-nation relationship with the United States since the inception of the country. Wabanaki people fought alongside colonists in the American Revolutionary War, but the US Congress never ratified agreements between the colonies and the Wabanaki. As Wabanaki people lost their legal appeals, state and federal agencies attempted to assimilate Wabanaki people—and their large land holdings—into the dominant white culture.

Micmac, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy communities were split by the establishment of Maine’s international border between the US and Canada. Countries claiming Wabanaki territory fluctuated, along with the border line, for about 60 years— starting roughly with the Treaty of Ghent in 1783 and ending with the Webster-Ashburton Treaty that resolved the Aroostook War in 1842.

Today, like all 573 federally recognized tribes in the United States, the Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Tribes are sovereign nations. They manage large tracts of tribal forest lands, operate governments, support educational and environmental initiatives, speak distinct languages, and administer cultural centers that work to foster language preservation and cultural traditions like basketmaking in Maine.

Self Governance

Wabanaki people have dual citizenships in their Tribal nation and the United States. Indigenous citizens are the only people in America that do not have to relinquish their national citizenship to also be a US citizen. While most Tribes in America have requirements for enrollment, the Tribes are not all recognized by the federal government.

Gina Brooks "Indian" jacket, Fredericton, New Brunswick, 2018

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

The four federally-recognized Tribal Nations in Maine have always had a form of internal government. They maintain Tribal governments, community schools, cultural centers, and manage Tribal lands and natural resources. Tribal councils govern the Nations, with an elected Chief (also called a governor) as the head of the executive arm of government. In the past, the post of Chief was hereditary.

The Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians is comprised of 1700 members as of 2019, and led by elected Tribal Chief Clarissa Sabattis. They received federal recognition in 1980. Since then, they have built a tribal center on their lands along the Meduxnekeag River near Houlton. Many Maliseets refer to themselves as Wolastoqiyik, "people of the Saint John River."

The Aroostook Band of Micmac Indians has 1240 members, and is led by Chief Edward Peter-Paul as of 2019. They received federal recognition in 1991 after a long process of research and petitions to the US government.

The Passamaquoddy Tribe has two reservations in Washington County and 3369 Tribal members. Motahkokmikuk is located 50 miles inland at Indian Township and as of 2019 is led by Chief William J. Nicholas Sr., and Sipayik is on the ocean at Pleasant Point led by Chief Marla Dana. The Passamaquoddy continue to inhabit their ancestral homeland 400 years after European contact. They received federal recognition during the 1970s after the Passamaquoddy v. Morton case was affirmed on appeal in 1975.

Penobscot Indian Nation is one of the oldest continuously operating governments in the world. There are 2398 Penobscot Nation members, with tribal headquarters at Indian Island, in the Penobscot River near Old Town. As of 2019, they are led by Chief Kirk Francis, and received federal recognition during the 1970s after the Passamaquoddy v. Morton case was affirmed on appeal in 1975.

There are many Wabanaki people living throughout Maine, as well as non-federally recognized Abenaki people.

Indigenous philosophy and resource management

The culture hero Gluscabe’s (also Glooscap, Gluskabe, Klooscap) teachings are passed down from generation to generation through oral histories, language, and songs, ensuring mutual responsibility and obligation between human and non-human beings.

Gluscabe histories are part of a melding of culture and science called Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) or Indigenous Knowledge (IK), where place-based understandings adapted over millennia inform decisions about sustainable practices. TEK/IK is supported by Indigenous spiritual traditions, ethics, and ceremonies.

Forced assimilation and diminishment and extraction of natural resources dramatically changed the ways Wabanaki people accessed and used the environment they had depended upon for thousands of years. The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980 restored a portion of the traditional land base. Since then and today, Wabanaki are once again supervising decisions about ecological stewardship based on TEK/IK.

Gluscabe’s oral histories teach the reciprocal relationship between people, animals, and the environment. Wabanaki people recounted their oral histories about the origin of animals (including humans), landmarks, and the way people live the region now known as Maine to author Charles Leland, who published them in 1884.

Passamaquoddy artist Tomah Joseph illustrated Leland’s book, Algonquin Legends of New England or Myths and Folk Lore of the Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Tribes. Many stories recount the consequences of over harvesting or hoarding resources,

Tomah Joseph was a respected artist, culture bearer, and an ambassador for Passamaquoddy people. He worked as a guide on Campobello Island where he met and befriended a young Franklin Delano Roosevelt, future president of the United States.

The River To Which I Belong

Wabanaki leader Polin travelled from Maine to Boston in 1739 to protest the damming of the Presumpscot River, on which his people depended on for sustenance. Meeting Governor Jonathan Belcher, Polin said he desired “only that a place may be left open in the dams so that the fish may come up in the proper seasons of the year.” In return, he offered to continue to share space with settlers, with certain restrictions.

Polin was protesting the great dam that Colonel Thomas Westbrook, a military leader and the King’s Mast Agent, was building to support a growing colonial logging industry. Polin observed that the dam blocked the vital fish runs on the “river to which I belong.” Governor Belcher ordered that Westbrook “leave open a sufficient passage for the fish…in the proper season.” But Westbrook defied the order. In order to protect the fish and the river, Wabanaki people targeted dams, mills, and upriver settlements for the next 17 years.

The Friends of the Presumpscot River have successfully promoted river and salmon restoration since 1992, pushing for fish passageways and dam removals in Falmouth and at Saccarappa Falls in Westbrook. They created a memorial in Westbrook in 2018 noting Polin as, “the first advocate” of the Presumpscot.

Phips Proclamation and scalping bounties

CAUTION: contains graphic and disturbing language

To secure land for English settlement, Massachusetts offered bounties on Native people in the early 1700s—specifically on their scalps. In June 1755, a Declaration of War against all Eastern Indians—except the Penobscots— was released. When the Penobscot diplomacy failed and they refused to fight alongside settlers, Massachusetts governor Phips issued this proclamation in November, expanding the war to include the Penobscot Nation.

The proclamation is genocidal, providing settlers freedom in “pursuing, captivating, killing, and destroying all and every” of the Eastern Indians. Bounties for scalps ranged from 20 to 50 English pounds for men, women, and children of any age. By June 1756, the Massachusetts assembly voted to raise the bounty to 300 pounds per person—equal to about $60,000 today.

Originally used as a tool for sanctioned violence, today, by making the Phips proclamation visible to the public, Wabanaki people are reaffirming their rights.

Fishing on the Androscoggin

English settlers in Brunswick noted the Androscoggin's abundant fish runs. In 1673, a commercial fishing operation at Pejepscot Falls took 40 barrels of salmon and more than 90 kegs of sturgeon in three weeks' time.

James E. Francis kapahse (sturgeon) drum, Indian Island, 2019

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

For the Wabanaki, the fishery was hoarding, and caused an imbalance with the fish populations. In 1737 residents of Brunswick petitioned Massachusetts to maintain Fort George, since they claimed the Wabanaki, “look upon us as unjust usurpers and intruders upon their rights and privileges, and spoilers of their idle way of living. They claim not only the wild beasts of the forest, and fowls of the air, but also fishes of sea and rivers, and so with an ill eye looks upon our Salmon fishery, and no doubt would disturb our fishers were it not under the Immediate protection of the fort.”

By the early 1800s, mill dams in Brunswick, Topsham and Lisbon Falls had destroyed the Androscoggin River's fish runs. In 1816 the last Atlantic salmon was seen at Great Falls in Lewiston.

19th and 20th century mill operations dumped waste into the Androscoggin, and extensive dams further degraded the water. The Clean Water Act of 1972 regulated pollution levels. Today, the Androscoggin River is clean enough to support several fish and wildlife species, but not subsistence consumption of them.

Pere Pole

Pere Pole was an Abenaki who lived with his family and community on the Ameskonti (Sandy) River—current day Farmington—when English settlers arrived in 1780. Pere Pole had served in the American Revolution and owned 100 acres in Strong.

Pere Pole was deposed as part of a land dispute against the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. After having his honesty and character vouched for by English settlers, Pere Pole was allowed to testify.

Pere Pole identified the fishing activities and names of the different sections of the of the Ammoscongon (Androscoggin) River. He shared the Wabanaki names of Quabacook (Merrymeeting Bay), Amitgonpontook (the falls at Lewiston), Rockamecook (the corn planting grounds at Canton and Jay Points), and that Atlantic salmon ascended the river in great numbers as far as Rumford Falls. His signature is a moose.

Leadership through basketmaking

Wabanaki people have been making baskets for thousands of years, continually innovating while simultaneously fostering traditions. Basketmaking today is about making art, stewardship of the environment, preserving cultural heritage, commitment to family, pride in identity, and honoring spiritual connections.

By the mid-1800s, colonialism changed Wabanaki lifestyles. Paired with loss of access to traditional lands, the Wabanaki were left with few resources. Enterprising Native people began making and selling baskets in order to survive, modifying utilitarian forms to fit Victorian tastes, and the rise of a new genre of basketmaking—fancy baskets—evolved.

From the 1870s to the 1930s, basketmaking boomed as Wabanaki people connected with tourists in resort areas like Bar Harbor, Poland Springs, and on the reservations. By 1900, basketmaking was the primary source of income for many Wabanaki families, supporting an independent way of life that mirrored traditional mobility of traveling to the coast in the summers to sell baskets, and inland in the winters.

As Native and non-Native cultures interacted, Wabanaki artists created new and exciting designs to meet the tourist market, including glove boxes, sewing accessories, powder dispensers, and wall pockets—sometimes in fanciful shapes like acorns and strawberries.

Brown ash is integrally tied to Wabanaki creation histories and the tradition of weaving baskets. With the Emerald Ash Borer beetle and climate change threatening ash trees in Wabanaki territory, questions about sustaining culture without a plentiful supply of ash arise. Wabanaki artists are exploring, and creating traditional basket forms with alternative materials, like cedar, metal, wool, and plastic.

Until around 1990, artists didn't sign their baskets, and the collectors usually didn’t record the names of the artists. Historically, tourists didn’t view the baskets as artwork, but rather as a memento of a nostalgic encounter with another culture, to recall trips to places like Bar Harbor or Indian Island, or as décor and useful objects in the large summer “cottages” on the coast.

Weaving knowledge, techniques, and tools are handed down through families. Within the Tribes, specific basket forms and designs are designated as familial heritage. By the mid-1880s, new technologies improved the manufacturing of tools like wood splitters, gauges, and blocks for holding a basket’s shape, which helped Wabanaki basketmakers create smaller and fancier baskets. The introduction of commercial aniline dyes in the 1860s allowed for a brighter and more varied basket color palette.

The Business of Baskets

Making baskets is a communal and intergenerational activity. The weaving of a basket is the end product of months of gathering and preparing materials.

Lucy Nicolar (1882-1969) was a nationally-known performer and businesswoman. A member of the Penobscot Nation, she grew up on Indian Island.

Nicolar, a mezzo-soprano, performed as “Princess Watahwaso” and recorded with Victor Records. Lucy Nicolar met and married Bruce Poolaw, from the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, while they were traveling across the country performing on the theater circuit. In this photograph, they are dressed in Plains-style regalia from Bruce Poolaw’s Kiowa tribe.

Nicolar returned home to Indian Island with Poolaw after the 1929 stock market crash. Together, they opened Chief Poolaw's TeePee in 1947, a tourist destination store that featured Penobscot artwork. In 2019, the TeePee is a small museum dedicated to the Nicolar family, run by their descendant, Charles Shay.

Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance

The Depression, World War II, changing demographics, and the shifting tourist market contributed to a decline of basket making in the mid-twentieth century. Dedicated basket makers continued weaving despite the economic challenges, and were instrumental in forming the Maine Indian Basketmaker’s Alliance (MIBA).

In 1993, a group of 55 basket makers from the Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes formed the Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance to save their own endangered art of ash and sweet grass basketry. By working together, MIBA lowered the average age of basket makers from 63 to 40, and increased numbers of artists to more than 150 through a series of inter-tribal workshops, apprenticeships, and markets. Pairing cultural and economic practices in their programing has continued to be central to their success.

Medicine and Health

Beadwork designs, especially those with three leaf floral motifs, often represent medicinal plants. People kept small pouches close to their body—in a pocket or worn as a necklace, and sometimes filled with herbs—to promote healing. While some designs are obvious, like a curled-up fiddlehead or a blueberry, others are more abstract.

Jennifer Sapiel Neptune, Penobscot beadworker noted, “When I look at the floral designs, I see plants that ease childbirth, break fevers, soothe coughs and colds, take away pain, heal cuts, burns and bruises, and maintain general health. For thousands of years these plants were used for healing by the Tribes in this area.”

Molly Molasses

Mary Pelagie Nicola (1775-1867), also known as Molly Molasses, was a member of the Penobscot Nation. She was a businesswoman, selling animal skins, baskets, and other artwork, and was known as a healer.

Later in life she sold photographs of herself in various poses, wearing her traditional Penobscot peaked cap, trade silver, wampum collar, beaver fur top hat, and checkered coat. A poem written for her by David Barker accompanied the photographs, including the stanza:

I write these rhymes, poor Moll, for you to sell

Go sell them quick to any saint or sinner

Not to save one soul from heaven or hell

But just to buy your weary form a dinner.

Molly Molasses was a lifelong partner to John Neptune, Lt. Governor of the Penobscot Nation from 1816-1865. He was the father of Molly’s four children.

Wabanaki Fashion

Wabanaki people have always designed and decorated their clothing in beautiful and innovative ways.

Access to manufactured trade materials around 400 years ago, like woven cloth and glass beads saved time from processing skins, stones, and shells, traditionally used for adornment. The introduction of brightly colored silk ribbons and standard sized glass beads from Europe led to a flourishing of innovation in Wabanaki adornment and fashion.

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/exhibits/holdingupthesky