(Page 1 of 8) Print Version

State of Mind: Becoming Maine explores Maine's Bicentennial. Installed March 13, 2020 through January 31, 2021 at Maine Historical Society in Portland. This online component expands content with Maine Memory Network items, and differs slightly from the physical installation.

Please visit Holding up the Sky: Wabanaki People, Culture, History & Art, a companion exhibition examining 13,000 years of Maine history.

Curated by Tilly Laskey, Maine Historical Society. Advised by Anne Chamberland, Archives Acadiennes, University of Maine, Fort Kent; Brittany Cook, Bicentennial Education Fellow, Maine Historical Society; Deborah Cummings Khadraoui, Abyssinian Meeting House; James E. Francis Sr. (Penobscot) Director of Cultural and Historic Preservation, Penobscot Nation; Bob Greene, Author, Portland, Maine; John Johnson, Portland, Maine; Daniel Minter, Indigo Arts Alliance; Kathleen Neumann, Manager of Education, Maine Historical Society; Lise Pelletier, Director, Archives Acadiennes, University of Maine, Fort Kent; Darren Ranco (Penobscot), Professor of Anthropology and Coordinator of Native American Programs, University of Maine; Jamie Rice, Director of Collections & Research, Maine Historical Society; Donald Soctomah (Passamaquoddy) Director, Passamaquoddy Cultural Heritage Center and Passamaquoddy Tribal Historic Preservation Officer; Elaine Tselikis, Communications & Grants Manager, Maine Historical Society.

Exhibition Contents and Navigation

Page 1 Wabanaki Homeland; Page 2 Explorations, English-speaking settlements, and border disputes; Page 3 The Northeast Boundary and Aroostook War; Page 4 French settlements and Acadien communities; Page 5 Black communities in Maine and Slavery; Page 6 Statehood; Page 7 Maine in 1820; Page 8 Becoming Maine.

The history of how Maine became a state is rooted in the stories of people. The separation from Massachusetts in 1820 had different meanings and implications for residents grounded in geography, culture, race, and economic standing.

This exhibition focuses on four distinct communities—Wabanaki, Acadien French, Black, and English-speaking people—all who have deep ties to the land now known as Maine. The Wabanaki have lived and cared for this land for millennia, and the French, Black, and English-speaking people have resided here since the early 1600s.

While multitudes of distinct cultural communities have, and continue to call Maine home, the Wabanaki, Acadien French, Black, and English-speaking communities were particularly impacted by the effects of statehood on existing treaties, sovereignty, land ownership, borders, slavery, citizenship, and colonialism.

When Maine entered the United States in 1820, the northern border wasn’t fixed, and most citizens had little knowledge about the far reaches of the state. Maine has been continually evolving over the past 13,000 years, into a state of "becoming" the place we know in 2020.

Maine is Wabanaki Homeland

Ancestral canoe journey, Motahkomikuk (Indian Township), 2019

Courtesy of Donald Soctomah, an individual partner

Wabanaki means People of the Dawnland, which includes the Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Abenaki Nations. They have inhabited what is now Northern New England, the Canadian Maritimes, and Quebec since time immemorial, according to oral histories, and for at least 13,000 years according to the archaeological record.

Wabanaki people are constantly adapting in response to changes in the environment, both small and dramatic. Their cultures have changed over time, with the development of unique political networks, philosophies, and a deep understanding of the landscape through Indigenous science.

Wabanaki ways of life radically changed with the coming of European explorers and settlers around 500 years ago. Epidemics, wars, genocidal bounties, treaties, land theft, and the splitting of ancestral territory through the establishment of arbitrary international and state borders all tried to erase Wabanaki culture and communities. In 2020, Wabanaki communities in what is now known as Maine govern themselves by Self-Determination and are recognized as distinct nations by the US Federal government.

The importance of Ash

Baskets are one of the oldest artforms in Maine. Often made of ash and sweetgrass, they are integrally tied to Wabanaki creation histories. Gluscabe (also spelled Glooscap, Gluskabe, Koluskap, Klooscap) is the main figure in Wabanaki oral history. When he shot an arrow into an ash tree, the Wabanaki people emerged—singing and dancing. Gluscabe taught Wabanaki people how to make tools, how to live, and showed them ways to understand and respect the land, the water, and all living things.

Root clubs and Sovereignty

The Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Tribes are sovereign nations, and have maintained a nation-to-nation relationship with the United States since the inception of the country.

Wabanaki people have always had a form of government. They maintain Tribal governments, community schools, cultural centers, and manage Tribal lands and natural resources.

Root clubs are usually made from the stem and roots of immature gray birch trees and are used as a weapon of war. They are also carried during special events, and sometimes a dancer will re-enact a war battle or hunting adventure using a root club.

Commemoration of the Bicentennial

Sovereignty is absolute. We are unique to this land. And with that uniqueness comes special powers of sovereignty. We’re still here today asserting our sovereignty. We’re not going to go away.

Reuben 'Butch' Phillips (Penobscot) 2001

The history of Maine did not begin at statehood in 1820. On the 200th anniversary of Maine separating from Massachusetts, it’s important to acknowledge that this land now known as Maine has been Wabanaki Homeland for at least 13,000 years.

The colonization of Wabanaki nations by Europeans and Maine’s path to statehood has been fraught with injustice, dislocation, and genocide enacted upon Wabanaki people.

Through listening to Wabanaki people, conversations around statehood at Maine Historical Society have been reframed to view the Bicentennial as a commemoration, rather than a celebratory event, and uphold Wabanaki experiences, authority, and sovereignty.

Where did Maine get its name?

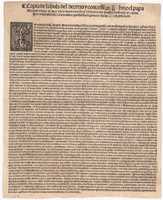

Ramusio's "Delle Navigationi et Viaggi," from 1565 referenced the mythical land of Norumbega

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

Maine has been called many names. Wabanaki—or Waponahkik—is the name the first people of Maine call their Homeland. It is traced to a Passamaquoddy place name, Ckuwaponahkik. The root wapon means both "light" and "things that are white in color"—ckuwapon refers to the rising sun. The ending, ahkik, represents a physical location. Ckuwaponahkik is interpreted to mean "the land of the dawn" more commonly known as Dawnland.

Europeans called the region by several names, including: Norumbega, Arcadia, Lygonia, New Somerset, and Acadie. In 1622, the land between the Merrimack and Kennebec rivers was called the Province of Maine for the first time, in a written land patent granted to Englishmen Ferdinando Gorges and John Mason.

The origin of the name Maine is unclear. One theory claims it’s named after the French province of Maine, or perhaps small village on the coast of England where Ferdinando Gorges’s family came from called "Broadmayne”, also known as Maine or Meine.

Some suggest the name comes from a practical nautical term for the mainland, distinguishing it from over 3,000 islands along the coastline.

Consequences of contact

About 500 years ago, Wabanaki people first received European visitors to their Homeland. Basque fishermen, European explorers, and French and English traders ventured into Wabanaki territories prior to attempts at settlement.

Trade was always important between Native people in the region, and later they incorporated Europeans into the trading system. Furs of all kinds—but especially beaver—were exchanged for metal tools, guns, household items, clothing, alcohol and other items.

These casual interactions proved catastrophic for Wabanaki people. Along with the trade goods came diseases such as measles, chicken pox, and smallpox, from which Native people had no immunity. The arrival of European settlers from 1616-1619 coincided with devastating epidemics that killed up to 75% of the Native population in Maine, known by Indigenous people as the "Great Dying."

Doctrine of Christian Discovery and Domination

The Indians are tractable. The Lord sent his avenging Angel and swept the most part away.

Thomas Gorges, Deputy Governor of Maine, 1642

Starting in 1452, European monarchies used Doctrines of Discovery to legitimize colonization and genocide of people outside of Europe. The Doctrine provided a framework for explorers, in the name of their sovereign, to claim territories uninhabited by Christians.

The Doctrine of Christian Discovery issued by Pope Alexander VI in 1493 continues to adversely impact Indigenous Peoples throughout the world today. It gave Spain and Portugal exclusive rights to the lands "discovered" by Columbus the previous year, and suggested Spain owned,

…from the Arctic pole, namely the north, to the Antarctic pole, namely the south, no matter whether the said mainlands and islands are found and to be found in the direction of India or towards any other quarter, the said line to be distant one hundred leagues towards the west and south from any of the islands commonly known as the Azores and Cape Verde .

Indigenous Peoples, because they were non-Christians were viewed by Europeans as sub-human, and therefore their Homeland was considered vacant—justifying their dispossession and erasure. If the inhabitants could be converted, they might be spared. If not, violent acts were authorized, and Europeans readily enslaved or killed those who resisted. European leaders parceled out Native lands in charters and patents, eventually turning it into private property for settlers.

"We Walk On; Eternally" by James Eric Francis Sr., Indian Island, 2020

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

In 1755, in an attempt to clear the region for English-speaking settlements, Massachusetts lieutenant governor Spencer Phips issued proclamations that offered bounties for killing Native people. This proclamation required “his Majesty’s subjects of the province to embrace all opportunities of pursuing, captivating, killing, and destroying all and every” Penobscot citizens. Scalps were used as proof of the genocidal killings, with bounties ranging from £20 to £50 for men, women, and children of any age. By June 1756, the Massachusetts assembly voted to raise the bounty to £300 per person—equal to about $60,000 in 2020.

James Eric Francis Sr. (Penobscot) is a multi-media artist, a historian, and the Director of Cultural and Historic Preservation for the Penobscot Nation as of 2020. His deep knowledge of Maine history, Penobscot culture, and Indigenous landscapes informs much of his creative output. Describing the painting, Francis noted that,

The artwork urges the citizens of Maine to join hands with the Indigenous population of Maine and walk eternally into the future and move beyond the deadly acts of the past. The use of language, color, and symbolism helps to affirm our resilience as Penobscot people historically, presently, and into the future.

Francis meticulously painted a recreation the 1755 Phips Proclamation for the background of this monumental five by four foot work, with the Penobscot word for "We Walk On; Eternally" painted over the proclamation in red.

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/exhibits/stateofmind