(Page 5 of 8) Print Version

Black communities in Maine

by Bob Greene

For a state known as one of the whitest in the nation, Maine has had a remarkably long and strong Black presence. Centuries before Maine broke away from Massachusetts to become a state in 1820, people of color have fished and farmed, sailed and labored on the rocky shores of the most northeastern part of the United States.

The first recorded Black person in what is now Maine was Mathieu da Costa, an interpreter for French explorers Pierre Du Gua Sieur de Monts and Samuel de Champlain. They were part of an exploring party that set up camp on St. Croix Island and Port Royal, New Brunswick 16 years before the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock. Da Costa is believed to have been fluent in Dutch, English, French, Portuguese, Mi'kmaq and pidgin Basque, and both the English and the Dutch hired him to connect with Indigenous peoples in North America.

A 1672 court document describes "Anthony, a Black man." Anthony was Dr. Antonius Lamy and may have been Maine's first doctor. In 1753, there were 21 slaves in the area of Portland, Maine's largest city. By 1764, the Black population in Portland had increased to 44, while there were 322 Black people living in the territory of Maine.

Reuben Ruby participated at the birth of the Maine

By Bob Greene

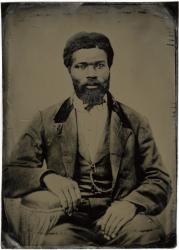

Reuben Ruby was a national leader in the abolitionist movement, demanding equal rights in the North as well as the South. And, following in his footsteps, three of his sons were active in politics. Yet Reuben Ruby is relatively unknown today.

In 1819, Reuben Ruby was 21 years old. Because the Maine Constitution allowed male residents, including Black men to vote, Ruby participated in Maine's first elections.

In 1827, he became the agent in Portland for Freedom's Journal, the first Black-owned newspaper published in New York City. The Freedom's Journal editorials attacked slavery and also encouraged free Black people to push for equal treatment in their communities.

Ruby became the first hack (horse-drawn taxi) driver in Maine in 1829. The next year, he transported William Lloyd Garrison around Portland and entertained the Boston abolitionist at his home with a dinner that included 20 members of Portland's Black community. Garrison described the men at the dinner as "gentlemen of good intelligence and reputable character."

It was on October 15, 1834, that Maine's anti-slavery organization was formed. Ruby was at the convention along with three White Portland citizens—Samuel Fessenden, William Coe and Isaac Winslow—and was one of the signers of the organization's constitution.

Ruby became involved with the American Association of the Free Persons of Colour in 1835, and that connected him to the Negro Convention Movement, several conventions held by Black people that aimed at a variety of reforms, including abolition and the fight for equal rights. A meeting at Portland's Abyssinian Church on May 18, 1835, selected Ruby and George Black to represent Portland at the meeting in Philadelphia. Ruby was elected president of the convention by the delegates. The convention created the American Moral Reform Society, of which Ruby was chosen as a vice president.

Ruby and his family moved to New York City around 1838. There, he worked as a cook and a waiter and even owned a restaurant briefly. He joined the California gold rush, earning as much as $3,000 during his short time in California before returning to Maine. In his later years, he worked for the Custom House in Portland, a job he obtained through his political connections.

The Abyssinian Meeting House

By Deborah Cummings Khadraoui

Creation of the Abyssinian Congregational Church, Portland, 1835

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

Six African American men founded the Abyssinian Religious Society in 1828. In 1831, church founder Reuben Ruby sold his plot of land on Newbury Street to build the Abyssinian Meeting House. It is the earliest meetinghouse associated with the African American population in Maine and the third oldest standing African American meetinghouse in the United States.

Ministers, community leaders and members of the Abyssinian Church actively participated in concealing, supplying, and transporting refugees from slavery, before and during the Civil War, as recounted in slave narratives and oral traditions.

Because of its easy access by rail and sea, Portland developed as one of the northernmost hubs of the Underground Railroad, the last stop before legal freedom outside the United States. When the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, it allowed slave owners and their agents to track down freedom seekers in the North and return them to slavery. Portland's activists reacted, providing escaped enslaved people safe houses and helping to organize escape routes to England and Canada.

The Abyssinian was a place for worship and so much more. It was a cultural center for the African American community during the 19th century, hosting abolition and temperance meetings, the Portland Anti-Slavery Society, and Negro Conventions. The Meeting House served as a school for African American children—one of only five in the United States at the time.

The Abyssinian Meeting House, as of 2020, is undergoing an extensive renovation to preserve the original character and intention of the building. A committed community group led by the Cummings Family has spearheaded the restoration.

The Maine Historical Society caretakes two bound volumes relating to the Abyssinian Church, including the Church record book and Society record book. Both volumes include extensive meeting minutes. Church records included member listings, vital records and baptisms, and a chronicle of liturgical occasions. The Society's book recorded financial transactions in addition to the organization's meeting minutes. The links below provide page level viewing of the record books.

View the completely digitized pages of the Abyssinian Church records from 1835 to 1876

View the completely digitized pages of the Abyssinian Religious Society records from 1839-1876

Watch "Anchor of the Soul" from 1994, co-produced by Shoshana Hoose and Karine Odlin. This documentary tracks African American history in northern New England through the story of the Abyssinian Meeting House in Portland. Courtesy of Northeast Historic Film

The impact of Black people on Maine

By Bob Greene

While a small number, Black people had an impact on the areas they called home. Richard Earle of Machias was Maine's first recorded Black patriot and hero. Earle was either the servant or slave of Captain Jeremiah O'Brien, who led the capture of the British ship Margaretta off Machias in 1775. Unfortunately for Earle, the Machias Union newspaper gave Earle's spot in history for running a supply vessel through the British blockage to London Atus, a Black man who was one of the first settlers of Machias.

A native of Cape Verde, Narcissus Matheas arrived in Bangor in 1834. At one time, he had seven wagons delivering baggage and express packages in Bangor, the FedEx or UPS of his day. He also owned and drove the first coach–a nine-seater bus–owned by a private individual in the Queen City of Bangor. A member of the Bangor Fire Department, Matheas was the first man in Bangor to deliver ice to individual customers.

Robert Benjamin Lewis was born in Pittston in 1802. He held three United States patents, including one machine to caulk the seams of wooden ships in order to make them watertight. The "hair picker" became a mainstay of Maine shipyards for years. Lewis also wrote the first world history book from a viewpoint of Black and Indigenous peoples, Light and Truth.

Macon Bolling Allen became the first African American lawyer in the United States when he passed the bar exam in Portland in 1844. He later moved to Boston where he became the first Black to become a Justice of the Peace.

James Augustine Healy was the oldest of 10 children born to Irishman Michael Healy and his enslaved wife, Mary Eliza. James was valedictorian of the first graduating class at Holy Cross College in 1849, and in 1875 he became the first Black Catholic bishop in the United States when Pope Pius IX named him to that post in Portland. Under Healy's administration, membership in the Catholic Church in his jurisdiction doubled to about 100,000 people, and he went on to manage the diocese of Maine and New Hampshire.

The Black work force in Maine

By Bob Greene

Jobs. It's a small four-letter word, but "jobs" is the key component of mass migrations, including Black people to Maine.

In the day of sail, Maine was a maritime power with tall, straight pine trees that were perfect for masts and sheltered harbors that were free of ice in the winter. In those days, when wind powered ocean-going ships, Portland was a day closer to Europe than Boston.

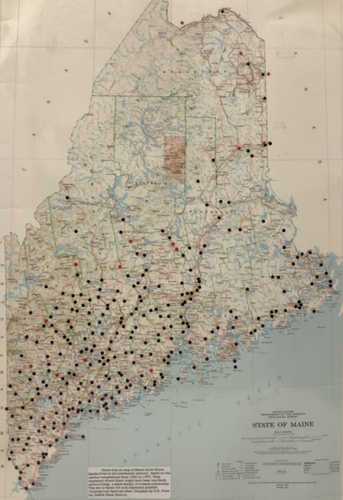

When Maine became a state in 1820, Black labor was prominent on the docks along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico ports. And that included Maine. Of the 359 Black men listed in the 1850 census of Maine, 194 worked on or at the water. The vast majority –157– were employed as mariners, sailors, seaman, fisherman, boatman, river boatman and lobsterman.

Other major seaports in Maine included Bangor-Brewer on the Penobscot River and Augusta-Hallowell on the Kennebec River. Today, the cities appear to be land-locked, but they were busy ports with sea-going vessels. The book The Story of Bangor tells how "in 1860 Bangor shipped 250 million board feet of lumber on the more than 200 ships a day that sailed downriver."

It wasn't until the Irish Potato Famine decimated Ireland during 1845-1849 and triggered a mass exodus to the United States where Irishmen replaced Black laborers on the waterfront. Portland's Black population declined until World War II, when two shipyards in South Portland needed workers. Again, Black people flocked to Maine for work, mostly in the Portland area. When the war ended and the shipyards closed, many of the newcomers left, looking for work in Boston or elsewhere.

The latest surge in people of color comes not so much for jobs but for safety. Many African refugees, fleeing war in their home countries, have settled in Maine where they feel secure. The newest Mainers have helped to revitalize the state, especially in Lewiston, the second-largest city in Maine, where many Somalians have decided to live and flourish.

The passenger steamer Portland was built in Bath in 1889, and was one of the premier side-wheelers of the Eastern Steamship Company. On a stormy November night during the ship's normal run from Boston to Portland in 1898, the Portland disappeared with all aboard, in what was later coined the "Portland Gale," a blizzard recorded as one of the worst storms of the 19th century.

The exact number of passengers and crew lost to the shipwreck is undetermined, since the only known passenger list went down with the ship. As a result of this tragedy, ships began leaving a passenger manifest ashore. It is estimated the loss was about 190 persons, including 17 Black crew members from the Portland community, who worked as seamen and in food service onboard the Portland.

In 2002, remains of the shipwrecked Portland were found upright and intact in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of Massachusetts.

The Black community in Maine, while small in numbers, is a microcosm of Maine history

Black communities are closely tied to the success of the Maine economy, initially as unwilling subjects through the institution of slavery and the triangular trade, and later as active participants and leaders in vital industries like maritime, shipbuilding, and service sector businesses. Most recently, the influx of New Mainers has boosted Maine's 21st century economy, with immigrant businesses generating $48 million in annual revenue in 2017.

The connection between Maine and the abolitionist movement—specifically the debates surrounding the Missouri Crisis that bound Maine statehood directly to slavery—provided a platform for the rights of Black people in Maine, demonstrated by Maine's Constitution that permitted Black men to vote in 1820.

Slavery in Maine and the Abolitionist movement

Slavery existed in Maine starting with the first English-speaking settlements, and while considered an institution of the American South, the profits from enslaving people helped build many of Maine's businesses and coastal communities. Wabanaki and Wampanoag people in New England were captured by English-speaking people and sold as slaves in Europe and the Caribbean. Scottish soldiers defeated by Oliver Cromwell were sold into slavery to labor in Massachusetts mills in the 1650s, eventually settling in York, Maine. Later, Maine shipbuilders and merchants participated in the slave economy through the triangular trading of lumber, molasses, and rum.

The Atlantic slave trade in the early 1600s brought African people as cargo to sugar plantations in the Caribbean, where New England merchants bought them in exchange for fish and lumber. Thomas Gorges, cousin to Ferdinando Gorges, advised against African slavery in Maine in 1642, noting that even if they could survive Maine's climate,

I could frame an argument against the lawfulness of taking them from theyr own country and soe have them and theirs.

Although enslaved people represented less than one percent of the population in Northern New England towns before 1700, their work as house servants and laborers greatly benefitted their owners and the region's economy.

One of the earliest documented African people in Maine was Susannah, an African woman who was about 20 years old when she was brought to Maine in 1686 as an enslaved person. Alexander Woodrup of Pemaquid purchased her, and she lived with him until 1689, when Wabanaki warriors struck Pemaquid. We know about Susannah's life because of a 1736 deposition she gave, recorded in York Deeds.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts outlawed the slave trade in 1787 in both Massachusetts and Maine. In time Mainers led the way in abolishing the institution of slavery in America.

Maine's Anti-Slavery Efforts

Organized anti-slavery efforts began after Maine Statehood in 1833, with the formation of the first Maine Anti-Slavery Society. The Portland group was integrated with Black and White members, and included both men and women, unusual for the time period.

Members acknowledged states' rights in slavery legislation, but remained committed to non-violence, and to convincing slaveholders that slavery was a crime against humanity and a sin against God. Their moral position on abolition alienated proslavery and antislavery supporters alike, since Maine's economy relied on shipping—especially along the East coast and into the West Indies. Ships from Maine did business with those that relied on slave labor, and cotton mills in Biddeford and Saco, Lewiston, and Waterville bought cotton grown by slaves on Southern plantations.

Because Connecticut, Massachusetts—and by extension, Maine—New Hampshire, and Rhode Island had outlawed slavery by 1787, Congress was concerned that Northern free states would become safe havens for runaway slaves, and created the "Fugitive Slave Clause" in 1793. Formally added to the US Constitution, it states that "no person held to service or labor" would be released from bondage in the event they escaped to a free state. The law also imposed a $500 penalty on any person who helped harbor or conceal escaped slaves.

Congress fortified the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, appealing to all citizens to assist in the capture of runaway slaves. Concurrently, the Underground Railroad reached its peak in the 1850s, with many slaves fleeing to Canada to escape US jurisdiction. It wasn't until June 28, 1864, that Congress repealed both of the Fugitive Slave Acts.

The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of people, Black as well as White, who offered shelter and aid to escaped slaves from the South. The Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850 made capturing escaped slaves a lucrative business. Fugitive slaves were typically on their own until they reached certain points, like Maryland, farther north.

Most Underground Railroad conductors were ordinary people, farmers and business owners, as well as ministers. Hiding places included private homes, churches and schoolhouses. For an escaped enslaved person, the Northern states were still considered a risk because they could be captured and returned at any time, so many made their way to Canada, which offered Black people freedom.

The Underground Railroad ceased operations about 1863, during the Civil War.

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/exhibits/stateofmind