A Convenient Soldier: The Black Guards of Maine was guest curated by Asata Radcliffe, a writer and multi-media artist, and installed at Maine Historical Society's Showcase Gallery on September 23, 2020. Images courtesy of Maine Historical Society and Monson Historical Society.

The Black Guards were African American Army soldiers sent to guard the railways of Maine during World War II, from 1941 to 1945. The purpose of their deployment was to prevent terrorist attacks along the railways, and to keep Maine citizens safe during the war.

This exhibition examines the day-to-day lives of the soldiers in three locations in Maine who stood watch during a time of racial segregation in the country and the military—a watch that embodied the incongruity of loyal citizen-soldiers who straddled the complex transitions of racism—a citizenship that was exercised as a matter of convenience during war-time.

I felt moved to merge art and history into an archive containing a presence that lives within this art installation. I want these men to be felt, not appropriated. Because I am not from Maine, I’ve been processing my place within this historical work. I’m not from here. I’m not from New England; thus my voice as an artist is that of a secondary witness.

I am drawn to the history of these soldiers as a person "from away" who is of Black and Indigenous heritage. The isolation that I felt moving to a predominantly White state and going through my first winter in Maine was intense. I started to think, "what was it like for them–the Black Guards? How did they survive harsh winters?" These Black men had to be very cautious when they needed to go into town. These are the realities I currently experience as a resident of Maine in 2020. I can imagine the isolation must have been even worse for them in the 1940s as they served in a military that was segregated until 1948.

In Maine, the Black Guards slept in boxcars—and then what did they return to at home? Segregation. The KKK. Lynching was a common practice then, especially in the south. It is possible that some of these men joined the military to escape those conditions of white supremacy only to find themselves ostracized and isolated, but still obligated to be of service to this country.

White supremacy is the reality in Maine that I experience today, thus a personal connection was made to their experience. This is exhibit is an artistic expression of that connection.

Asata Radcliffe, Guest Curator

September 2020

Royal River Grand Trunk Railroad, North Yarmouth

During World War II, fears of terrorist attacks along Maine’s borders prompted the deployment of Black Army soldiers to guard the railways and bridges. According to the research of Dr. James Pratt, whose father was stationed as a Black Guard at Vanceboro, this battalion of men belonged to the segregated 366th Infantry Regiment that was organized at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, ten months prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

I feel compelled to tell the story of these men from a place of authenticity, rather than as a researcher. As I look at these men who were deployed to guard the railways of Maine, they lived in a boxcar. We know how severe Maine winters are. This is another example of how the United States treated soldiers. The Black Guards' presence here, like mine, was transitory.

The soldiers arrived in North Yarmouth in January 1941. According to members of the Arthur and Edith Atkins family who owned a farm near the bridge, the soldiers were regarded as "polite young men who stood guarding the bridge through the bitter windy cold of winter and the heat of summer." The Atkins family embraced the soldiers, though it was cited that, "the soldiers had a white major who wasn’t as decent to the young soldiers as some of the local residents were."

—Asata Radcliffe

Photos of Black Guard soldiers in North Yarmouth

Onawa Trestle Bridge, Morkill

Starting in 1942, soldiers from the 366th Infantry Regiment lived in boxcars at Morkill and began guarding the Onawa Trestle.

According to veteran railway worker and now deceased Bob Roberts, there were about 16 guards who were stationed at the Morkill trestle. One of the boxcars functioned as their kitchen. The soldiers served their watch on the bridge 24/7, rotating out every 12 hours. On one occasion, the men performed for the community in the Onawa Memorial Hall.

Mr. Roberts told me stories of the Black Guards in Morkill, including that their time there wasn’t without incident. In their due diligence, the soldiers discovered dynamite below the Onawa Trestle. It was unclear to the soldiers and residents how and why the dynamite was there, and the assumed conclusion was that the responsible culprits were local loggers who may have inadvertently left the dynamite. On another occasion, one unidentified soldier did not hear a train coming one night and was hit, his leg severed, and he bled to death.

—Asata Radcliffe

Photos of Black Guard soldiers in Morkill

Passadumkeag Railroad Bridge, Old Town

The Black Guards' post at Passadumkeag Bridge near Old Town is one of the most contentious that has been discovered in the archives. John Coghill, owner and editor of the Penobscot Times newspaper, wrote racist and inflammatory editorials to gather support to have the soldiers from the 366th removed from town.

Newspaper clippings indicate that the first group of soldiers, 50 in number, arrived in Old Town in 1942. A deeper search to find newspaper articles that may have recorded more events and editorials during this time are missing from the digital archive. Any accounts of the soldiers' time in Old Town were recorded from the point of view of the Penobscot Times.

These newspaper clippings shed light on the fact that the soldiers faced racism in Maine during their service to guard the railways and bridges.

—Asata Radcliffe

Penobscot Times Newspaper Articles

Black Guards face racism in Old Town

Penobscot Times, March 20, 1942

Sportswriter Otis LaBree wrote a favorable welcome when the Black Guard soldiers first arrived in 1942.

Though the soldiers were there to protect the bridges near Old Town during WWII, shortly after this article was written, the soldiers faced a war of their own waged against them by the editor and owner of the Penobscot Times, John “Jimmy” Coghill.

The Arrest

Penobscot Times, June 5, 1942

Two of the Black Guard soldiers, Pvt. Edgar Collins and Pvt. Oscar White were accused of allegedly inciting an attack on a local man. The soldiers were immediately arrested and jailed.

During the months prior to this arrest, there had been many articles written by the editor of the Penobscot Times, John Coghill, along with a petition he had circulated throughout Old Town calling for the removal of the soldiers. Coghill even sent a request to Maine's U.S. Senator and former governor, Ralph O. Brewster asking for White soldiers to replace the Black Guards.

Brewster, a former governor of Maine, was associated with the Ku Klux Klan. He was the only Maine politician openly associated with the Klan to be elected in Maine.

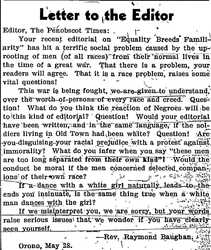

Editorial by Rev. Raymond J. Baughan

Penobscot Times, June 5, 1942

Though many of the 1942 Penobscot Times articles that document Coghill’s mission to remove the Black Guard soldiers are missing from the archives, this letter to the Editor offers evidence to showcase Coghill’s racism as Rev. Raymond Baughan of the Universalist Church in Orono referenced a previous editorial written by Coghill entitled Equality Breeds Familiarity. The issue containing Coghill’s editorial is missing from the newspaper’s archive.

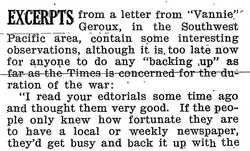

Support for Editor Coghill

Penobscot Times, March 24, 1944

This letter to the editor, written by former Marine Evan C. Geroux, is evidence of racism by the townsfolk of Old Town, who openly expressed their congratulations to Coghill for leveraging his power as editor of the Penobscot Times to undermine the service of the Black Guard soldiers.

Racism continues in Maine

In January of 2017, the KKK left fliers in Freeport, announcing their presence just days after the presidential inauguration. The guest curator lived in Freeport during this horrific incident. The impact was devastating.

Though this was a shock to many Freeport residents, others were aware of the Klan’s presence and political power in the state of Maine, dating back to the 1920s. Over 40,000 members of the KKK in Maine helped to elect Ralph Brewster to the office of Governor of Maine in 1924 and 1926. Though Brewster denied being a member of the Klan, one does not have to don a white robe and hood to activate white supremacy within the legislative realm.

Brewster's friendship with John Coghill was proof of that as Brewster utilized his power to oust the Black troops that were stationed near Old Town.

Many of the Black Guards originated from the south where the KKK had been active since the organizations' inception in 1865. As we confront the reality of racism in Maine, it is vital to highlight the very real threat the Black Guards faced while on their watch in Maine during the early 1940s. It is not enough to simply celebrate the Guards' heroic service in Maine. It is just as important to acknowledge the reality America delivered to these men, whether at home, or on duty. These men were courageous enough to show up to serve a country in which the oppressive forces of white supremacy dictated every aspect of their life, including serving in a segregated military. Though there are a few instances where the soldiers were embraced, the reality in which they lived was not of a full, humanized citizenship.

If America is to fully acknowledge and reconcile its hypocrisies that are rooted in and perform as systemic white supremacy, what is demanded in this moment is a full reckoning of the impact white supremacy has had on the experience Black people in America. These soldiers need to be honored for the totality of their experience in Maine.

—Asata Radcliffe

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/exhibits/convenientsoldier