(Page 7 of 9) Print Version

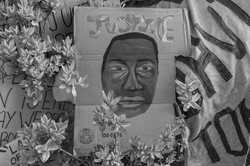

All Men are Created Equal

Why is Maine so White?

Within a few days of moving to Portland in 2014, I first heard the phrase "from away." To me, a new Black Mainer, the use of the phrase seemed alienating and designed to reinforce the demographic profile that keeps Maine listed as one of the Whitest states in the Union.

When a Maine Public Radio listener posed the question, Why is Maine so White? in 2019 the initial response pointed to the lack of plantation farming inferring that Maine's reliance on "forestry, shipbuilding and textile and mill industries" made it immune to slavery.

Black people have been in Maine since the first settler colonialists arrived. Even though Maine was established as a free state under the Missouri Compromise in 1820, slavery was present since the 1600s in Maine and Mainers continued to benefit from slavery elsewhere in the U.S. and around the world after statehood.

Despite being home to prominent abolitionists such as General Oliver Howard or Samuel Fessenden, in general, White Mainers were not immune to the lure of slavery or to the narratives that dehumanized the enslaved. This response raises its own set of complexities and exposes Maine's dual identities that exist today.

Maine is where Macon Bolling Allen, the first Black attorney in the United States, was admitted into practice on July 3, 1844. Maine is also the place where the multi-racial community of Malaga Island residents was forcibly removed by the governor's edict in 1912.

Maine is the home of the 20th Maine Infantry Regiment which, despite impossible odds (and no ammunition), refused to retreat in the face of Confederate soldiers. Their courage and heroism played a decisive role in the Battle of Gettysburg and the Union victory in the Civil War. And, Maine is the place where, just a few miles outside of its major cities like Portland, Lewiston-Auburn, or Bangor the Confederate flag is prominently displayed.

Maine is a state with two conflicting identities—which Maine will win? The Maine that will be remembered by future generations is the Maine that we choose to nurture now.

—Krystal Williams

Restrictive covenants and race

From the Doctrines of Discovery to 2021, the systematic dispossession of land and exclusion from land ownership has been a primary way in which wealth has inured to White America. At the turn of the 20th century, ordinances across U.S. cities and towns used racially-explicit zoning laws to segregate the races.

When this practice was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1917, private developers created racially restrictive covenants. Such covenants were agreements entered into by groups of property owners or subdivision developers that kept them from selling their property to specified groups because of race, creed or color for a definite period unless all other property owners in that subdivision or community approved of the transaction. Restrictive covenants became the dominant mechanism to keep non-Whites (and, in many cases, Jewish Americans) out of communities throughout the 1920s through the 1940s. Restrictive covenants "ran with the land," meaning that the restriction became inherent to the property itself. Restrictive covenants were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1948.

The practice of redlining, in which lines were drawn on city maps to define ideal geographies for bank investments and mortgages, co-existed with restrictive covenants. Unsurprisingly, the most favorable areas for bank investment were also areas where restrictive covenants ensured all-White communities. Although the practice of redlining was made illegal with the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the damage had already been done – communities were already established, the seeds of wealth were already planted, and generations of Americans were used to segregated living. As homeownership and wealth data show, the vestiges of these practices are still with us.

Redlining and the Jewish Community

In the 1930s, Portland's bankers and real estate agents systematically discriminated against Catholics and Jews through the practice of "redlining." They defined neighborhoods with a significant "foreign-born, negro, or lower grade population" as "hazardous" and, in so doing, rendered homeowners in those neighborhoods ineligible for mortgages or other property-based loans.

During the same period, Portland's political elites also revised the city's charter to dilute the political power of residents in these neighborhoods. An insurance map, annotated in 1935, draws particular attention to the large number of Irish, Italian, Jewish, and Polish residents in the Bayside, East End, and Munjoy Hill neighborhoods.

Portland was home to over 600 Jewish households in 1930, 87 percent of which had immigrant heads of household. These Jews, however, were more likely to own homes than other Portlanders, an indication of their relative affluence. In part due to the discrimination they experienced downtown, many Jewish families were prompted to move to other neighborhoods, particularly the rapidly growing Woodfords area.

Some wealthy Jews sought to move to high-status towns like Cape Elizabeth, but real estate agents consistently prevented them from doing so. Jews built new synagogues in Woodfords in the 1940s and '50s, abandoning properties in their old neighborhoods like Anshe Sfard.

—David Freidenreich

Pulver Family Associate Professor of Jewish Studies, Colby College

Civil War soldiers assisted formerly enlsaved people to settle in Maine

After the Civil War, as Commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau, General Oliver Otis Howard was responsible for integrating the newly freed Black people into a way of life that was alien and often hostile.

General Howard was also responsible for relocating George Washington Kemp and his family in 1865. Kemp had served with Charles Howard and his older brother, General Oliver Howard after escaping his enslavement in Virginia. Kemp told the story of his journey, saying that he and,

Seventeen other slaves slyly abandoned their master's plantation and enlisted in the army under command of Gen. O.O. Howard. Mr. Kemp, after remaining in service three years, gained the admiration of the General and was persuaded by him to come North to Maine and live, and take care of his farm, on which resided his mother.

General Howard also brought Julia McDermott, a former enslaved person to Maine with her two children at the end of January 1864, when he returned briefly on furlough.

Julia served as cook for Lizzie Howard and her four children in Augusta. At the end of November 1865, Julia married Frederick Brown at the Howard home. Brown, also a former enslaved person, had come to Maine with an officer of the 15th Maine Infantry in 1864.

We can only experience Julia's wedding through the beneficence of Lizzie Howard. I wonder, if Julia were able to tell her own story, on what small particulars of that day would she choose to focus? Would she share her joy at starting her own home with her children and Frederick, her new husband? Would she express feelings of relief, knowing that she, a former slave, could love her husband and children without reservation because there was no danger that they would be ripped apart at a master's whim? To love and be loved is the simplest and most profound of all human emotions, and it is made all the more so by the freedom with which it could now be expressed.

—Krystal Williams

Slavery and Anti-Slavery in Maine

Susannah, an African woman who was about 20 years old when she was brought to Maine in 1686 as an enslaved person, is the first recorded African slave in Maine. Although owning enslaved people was outlawed in Maine in 1783, broader American slavery faced little opposition in Maine until the formation of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. The Anti-Slavery Society's Portland group was integrated with Black and White members, and included both men and women, unusual for the time period.

The Anti-Slavery Society believed slavery was a crime against humanity and a sin against God. Their moral position on abolition alienated those whose livelihoods hinged on the Atlantic slave trade, including merchants, shipping, distilleries, and mills.

Before the Underground Railroad, some abolitionists worked to free enslaved people travelling in the north, by assisting their escape when the enslaved people were visiting places like Maine with their masters.

Reflections on the Last will of Charles Frost of Kittery and Berwick, 1724

One silver-headed loading staff, a plate-hilted sword, and one Negro man (Hector);

One tobacco box, one seal ring, one plate hatband, and one Negro man (Peince);

One riding horse (the best), furniture, pistols, and one Negro man (John); and

All the gold rings (except the seal ring), a steel-hilted sword, and one Negro boy (Cesar).

The riches (and sins) of the father passed to the sons.

Krystal Williams, 2021

Dancing through the race barrier

My name is Garrett Stewart, I am a third-generation Mainer. My grandparents, R. Allen Stewart, Sr. and Mattie Stewart came to Maine during World War II when my grandfather took a job at the South Portland Shipyard. Carrying on the family tradition, I was also a shipfitter at Bath Iron Works. I retired in 2020 due to a work-related injury. I am a member of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAMAW) Local S6 and I am the acting president of the A. Philip Randolph Maine chapter of the Maine AFL-CIO. I also serve on the Permanent Commission for the status on Racial, Indigenous and Tribal Populations in Maine. I feel it is very important to use my voice in today's social climate.

My father, Willie Stewart, was born on November 22, 1945, in Portland. He graduated from high school in 1964 and was considered one of the best athletes to attend Deering High School. In addition to football and track he was also a professional boxer with a 9-1 record fighting at the Portland Expo. My father was a hard worker and for most of his early life worked for my grandfather at Stewart Paving Company.

During the 1960s when he was a teenager, my father was a weekly guest dancing with White teens on the Dave Astor show—Maine's version of American Bandstand that was broadcast throughout the state on Saturday nights. Although this was a common sight for people in this area, Jim Crow was still segregating the South. I don't believe my father truly knew what a big deal that was at the time. He had been here all his life and had wonderful lifelong friends of all backgrounds.

—Garrett Stewart

Portland, Maine

My family and Malaga Island

When I look at the photos of my family on Malaga Island I have mixed emotions. In one way it's exciting because these images provide a connection to my grandfather and extended family that I hadn't had. It helps connect the dots of who we are. I love seeing the cozy home and relationships. I imagine what they did for fun and the ways that joy showed up in their lives. I wonder who in our family has what traits passed down and wonder what they'd think of us after all that has happened.

In other ways it's saddening, I only met my grandfather once as a child and had heard that he was troubled. I feel like what we now know about his life offers some insight into why he may have been that way. So much trauma and loss. Processing that could not have been easy. Feeling displaced and disregarded had to be infuriating.

I can't help but focus on their eyes in the images. I wonder what they felt in these moments. If they wanted to take the photo. If the person on the other end of the camera was a friend or foe. I wonder about their concerns, fears, and agency. I wonder how they found so much strength after being deemed worthless.

In other ways, the images are motivating. The Tripp family are the only remaining descendants of Malaga Island residents who identify as Black/African American. Despite the treatment, the Tripps are still here. We are thriving and living in ways that they may have only imagined. I look at these images and feel pride and am honored to carry on their legacy.

—Charmagne Tripp

Grammy Award-winning singer and songwriter

Indentured Servitude as a model for child labor and inequity

Societies have always grappled with how to support their poorest members, and Maine is no exception. In 1821, the year after Maine became a state, the legislature passed a law providing for the "Relief and Support, Employment and Removal of the Poor." Residents were assigned to towns, who were charged with supporting the poor and indigent through the work of special boards, the "Overseers of the Poor." At taxpayer expense towns created poor farms and tenements to house the poor, where they could work in exchange for food and shelter. This indentured servitude created classism based on inequity that opposed the Framer's sentiments that "all men are created equal."

Not surprisingly, towns sought ways to minimize their costs, and one of the most expedient strategies was a system known as "vendue," in which the poor were auctioned off to the lowest bidder, the town then paying the winning bidder for the care provided. These auctions often took place in a public venue such as the town square, in ways reminiscent of a slave auction.

When families fell on hard times the Overseers could bind out their children into apprenticeships with local farms and businesses. Boys could be indentured until they reached the age of 21, and girls until they turned 18 or were married, whichever came first. Masters receiving these children were supposed to feed, clothe, and educate them, in addition to teaching them a trade that would allow them to support themselves after their indentureship. Child labor through servitude served as a model for children's work in factories and mills.

Equal Rights Amendment of 1972

In 1923 the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was first introduced into Congress. Drafted by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman, it came soon after women won the right to vote through the 19th Amendment. Paul always understood that the vote would not solve all of women's problems. "We shall not be safe until the principle of equal rights is written into the framework of our government," she said.

Yet most women's organizations opposed the ERA over the worry it would be used to strike down laws protecting working women. Many believed the shorter workdays, minimum wage laws, age of consent and other protections women had fought so hard for were at risk. They argued that America wasn't ready. There were too few women in positions of power—such as legislators, lawyers, judges, employers and union leaders—to make good on the promises of the ERA.

Congress finally passed the ERA in 1972. Supporters were given seven years to get it ratified, later receiving a three-year extension. But by 1982, they were still three states short.

In the last few years, the three final states ratified the ERA; Nevada (2017), Illinois (2018), and Virginia (2020). Congress must decide whether to eliminate the original deadlines.

Section 1 of the ERA reads: "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." In 2021 it is astounding that, under our nation's—and our state's—founding documents, women are still not considered equal.

—Anne Gass

Voting, Suffrage and the Electoral College

Who is a citizen? Who can vote? These issues have been debated throughout our nation's history. The U.S. Constitution's framers recognized the importance of voting rights, who decided them, and how elections were conducted. This resulted in the system still in place today, where states generally manage elections, but Congress can also pass voting laws or regulations.

The Constitution first granted citizenship and voting rights only to White men who owned property—such as land or slaves—but eventually the property ownership requirement was dropped. This gave White men the power to fashion a system of laws that privileged their interests above those of others.

Extending the vote to groups other than White men would prove far more difficult. It took the Civil War to enfranchise Black men, through the combined power of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. It was another half-century of struggle until, in 1920, the 19th Amendment was ratified through which most—though not all—women won the right to vote.

Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, which finally recognized Native Americans as citizens, but they couldn't vote until 1962. In Maine, Native Americans weren't allowed to vote in state elections until 1967.

Today, the tug of war over voting rights continues. The U.S. Supreme Court's 2013 decision for Shelby County vs. Holder eviscerated many of the protections of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In the 2020 election, states loosened voting restrictions to keep people safe during a dangerous pandemic, but in 2021 many states are seeking to roll those back and take further steps to restrict voting access.

There is also serious debate over eliminating the electoral college and instead using the national popular vote to elect the U.S. President. The electoral college was a compromise by the Constitution's Framers. Further, it gave Southern states an outsize share of power by allowing them to count three-fifths of their slaves in apportioning votes (even as they were denied voting rights). The system has been criticized because it is currently possible for candidates to win the popular vote, but lose the electoral college, as happened in 2000 and 2016.

Clearly, we are still striving to achieve the "more perfect union" envisioned by the preamble to the United States Constitution, that "secures the Blessings of Liberty" to all Americans.

—Anne Gass

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/exhibits/beginagain