(Page 3 of 8) Print Version

The Nature of Collecting

Natural History museums relied on a wide range of people for their collections, including scientists, rare art collectors, and tourists, often bringing together evidence of Indigenous people, their “artifacts”, and fossilized evidence of long extinct animals alongside one another. While this clearly places Indigenous people as part of a “Natural” past, these practices of collection and display had real consequences for Indigenous people.

As Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith points out in her 2012 book Decolonizing Methodologies,

The idea that collectors were actually rescuing artifacts from decay and destruction, and from Indigenous peoples themselves, legitimated practices which also included commercial trade and plain and simple theft.

For Indigenous peoples, including the Wabanaki, these collecting practices also prevented ongoing care-taking roles of these objects—and their removal caused harms to a range of cultural and ceremonial practices. As these “artifacts” make their way back to our Tribal Nations, Indigenous people re-engage them in ways that not only allows for Indigenous understandings of history, but also connects these pasts to the current day and make them a part of the future.

Cabinets of Curiosities

PSNH interior showing Penobscot canoe, taxidermy mounts, and display cases, ca. 1965

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

Museums are the keepers of “real stuff,” connecting us to knowledge that excites and promotes curiosity. The modern museum has roots in the 16th and 17th century practice of creating “cabinets of curiosities,” literal display cases filled with items like minerals, shells, fossils, mammal and plant specimens, and cultural items from Indigenous peoples and diverse cultures, mixed together in glass-door cabinets. The cabinets demonstrated the owner’s knowledge and expertise, and were subjects of conversation.

Sometimes, European collectors created entire “Wonder Rooms,” opening them to the public starting around 1650. However, the cabinets were often arranged for visual interest, without regard for an object’s context, or natural order.

The PSNH operated like a cabinet of curiosity, often lacking consistent protocols for cataloging and displaying donations or scientific collections. LM Eastman recalled the PSNH saying,

Books, shells, birds, plants, and mounted animals all appeared together. The specimens were not inventoried in specific categories, and many times the name of the contributor was not recorded. It seems that as the specimens arrived at the Society’s doors, a partial description was randomly jotted down on an entry sheet. This lack of organization and focus would be the foundation for modern criticism of collections of this kind.

From Moon Rocks to Birchbark Canoes

Cluster Quartz crystals in the Portland Society of Natural History, ca. 1965

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

The PSNH grew out of the Era of Enlightenment where regular people—citizen scientists—created societies and academies. Universities did not offer degrees in many scientific subjects, allowing individuals to self-professionalize through exploration and observation.

The term natural history is based on human domination of nature by naming, labeling, organizing, and creating theories about the environment. Today, we are living with the legacy of many artificial systems set in place by Europeans during the Enlightenment, which can actually distance humans from nature.

Natural history explorers created collections and mixed art, science, and history with biological specimens, taxidermy animals, fossils, and geology. PSNH Curator Edward Norton noted of the Elm Street location, “Nowhere in Maine or elsewhere can there be found such full representations of specimens from the State in so many departments of natural history under one roof.”

Over its 135 years of operation, the PSNH changed displays according to current scientific thought. After 1859, they embraced Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, showing how organisms evolved from single cells into the lifeforms we see today.

Arctic connections and exploration

Jennifer Sapiel Neptune's experiences in Greenland

In June of 2022 I traveled to Greenland as part of a small group of artists exploring cultural resiliency in this time of rapidly changing climate. Why Greenland?

We are connected by water and currents, by migrating Atlantic Salmon, by stories, ice, and climate change. As a traditional Penobscot basketmaker climate change is impacting the sweetgrass I harvest, the ash trees that I need for basketry splints, and access myself and other Indigenous cultural practitioners need to coastlines, rivers, plants, fish, and animals.

20,000 years ago where you stand now was covered in a mile of ice. An enormous ice sheet covered Wabanaki territory, and what we now call Maine. As the ice retreated north massive changes happened to this landscape, the Gulf of Maine, and all who inhabited it. Sea levels rose and fell, rivers were reborn from the ice, islands rose or sank under the sea, and some animals like Mammoths and Mastodons disappeared entirely.

Our people still pass down the stories of this time and how the world changed as we lived with, and beside, the Laurentide Ice Sheet. In Greenland I saw our stories come to life in their landscape. Witnessed shapes and otherworldly faces in the ice that had me constantly replaying in my mind every traditional story I know.

In a traditional story of how the Penobscot River was formed, a giant frog held back all the fresh water causing a water famine. The fish, the animals, and people were dying of thirst until Gluskap comes and smashes the giant, releasing all the water. Some people are so happy and relieved they jump into the flood and are turned into salmon, sturgeon, eels, turtles and whales. Imagine my surprise on day two in Greenland to stand in front of an ice formation shaped like an enormous frog with a smirk in his grin.

In Greenland I felt as if I was traveling with an entourage of ancestors, who shared in my joy and excitement of each experience that felt more like remembering than discovering. In Maine, Caribou were hunted out by unsustainable non-indigenous hunting practices a hundred years ago. In Greenland I cried when I tasted caribou meat for the first time, I felt surrounded by ancestors who had been starving, and my DNA and spirit had been starving too for nourishment that had been lost for so long I didn’t know I missed it.

Flying home, the clouds parted as we flew over the Labrador Sea. Looking down at the chunks of ice floating there, I thought about the endangered Atlantic Salmon who make the journey from their birth places in the Penobscot River watershed to the sea between Labrador and Greenland, to grow and return home to spawn another generation. Unlike Pacific Salmon they live to return to the sea again after spawning. Miracles with fins, too stubborn to die.

Looking out over the vastness of Labrador from my window, I recalled an old story about a woman from the far north who flew as a loon to our territory to warn the people about what was to come, to try to buy us a little more time before everything changed forever. There are things you can never get back. I wondered what she would say now, and would those that needed most to hear her warning most even be able to listen.

We belong to the same river

The salmon and us

pαnawάhpskewtəkʷ (Penobscot)

We were born for each other

Both as stubborn as the rocks

our home is named after.

We refuse to give up

We refuse to die.

In the spring if you are quiet

you might hear young skʷámekʷak (Atlantic Salmon)

Singing their traveling songs

as they swim for the Labrador Sea.

To grow strong and become wise

To meet the ice with the long memory

Where ancestors still dance the dance

of lights in the sky.

We remember

Far back, long ago, stories of the ice

The winters that didn’t end

Until Glooskap stole summer,

the ice retreated, defeated.

wαpskʷ, the white bear followed

those that stayed changed and adapted.

The rivers returned.

For thousands upon thousands of years

the land and waters rose and fell.

Change, adapt, in, out, retreat, advance

like a breath that takes eons.

Tundra retreated, abandoning plants and insects

that still hold their space on the very tops of the oldest,

most sacred mountains.

If I could, I would

Bend the straight linear west

back into a circle, back to the dawn.

Save us all from the pit of grief

which comes with living a dystopian race

of metal, greed, and longing

that moves too fast to adapt and

leaves the plants atop Katahdin weeping

as the summer marches further north.

There is no end to the loneliness

Grief over what can never, ever be returned

And it is not just the fate of fish

Or one small tribe of people

Our fates all tied to the smallest of beings

We are all endangered

We are all in danger .

--Jennifer Sapiel Neptune ~ January 2023

Walrus and Narwhals and Robert E. Peary

By Geneveive LeMoine

Curator/Registrar

The Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and Arctic Studies Center

Bowdoin College

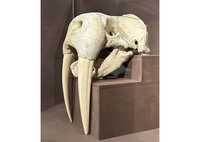

Walrus and narwhal are quintessential Arctic marine mammals, adapted to living on and under sea ice. When PSNH member, Robert E. Peary, collected these walrus and narwhal specimens in northern Greenland in the 1890s there was considerably more sea ice in the Arctic than there is today. At the beginning of the 20th century sea ice began a steady, and now accelerating, decline that continues today, putting these animals at risk as their habitat disappears.

Walrus eat clams and other bottom-dwelling creatures, consuming thousands a day. When not swimming and diving, they use their tusks to haul themselves up on floating ice, called floes, in relatively shallow coastal waters close to abundant sources of food. This is particularly important for mothers and babies, as the calves can stay safely on the ice as their mothers forage on the bottom. Due to climate change, ice is no longer in the Bering Sea’s shallow coastal waters, forcing females to swim great distances to feed.

Narwhals eat mostly fish, often diving to great depths in search of halibut, polar cod, and squid. The males’ dramatic tusks remain something of a mystery to humans, although recent research has revealed that they may be able to sense changes in temperature, salinity, and water pressure.

Narwhals spend summers in ice-free bays and fjords. In winter these places develop solid ice that narwhals cannot break through, so they migrate to deeper water where they swim under dense pack ice, surfacing through cracks to breathe. Recent studies have shown that narwhals are staying longer in their summer feeding areas, as ice is forming later in the fall. This puts them at risk of entrapment if ice forms too quickly, as it can do, and also exposes them to more shipping traffic, which they find very stressful.

We are all Connected

We are living during a rare time of geological change, moving out of the Holocene, that began after the last ice age about 12,000 years ago, into the Anthropocene, named because of the outsized human domination of the earth.

The world’s biodiversity is vulnerable to collapse during the Anthropocene era because of human activities that have compromised habitats and warmed the climate. According to 234 scientists from 66 countries who prepared the United Nation’s Code Red for Humanity report, the earth’s surface temperature has increased faster since 1970 than in any other 50-year period over the last 2,000 years and global mean sea levels have risen faster since 1900 than over any prior century in the last 3,000 years. Climate change, species extinction and biodiversity are linked. In 2019, United Nations scientists reported that one million species are threatened with extinction, the highest number in human history. The World Wildlife Fund observed in 2022 an average of 68% decline in the global population of mammals, fish, birds, reptiles and amphibians since 1970. Freshwater populations declined by an average of 83% since 1970, more than any other species group.

Modern human activities over the past 200,000 years have unintentionally brought the earth to this critical place. Biodiversity loss both contributes to climate change and is a result of climate change, showing our interconnectedness. Scientists suggest that we must treat climate change and biodiversity loss simultaneously, or neither will be solved.

Beavers and Top hats

At the PSNH’s Elm Street location, curator Edward Norton noted that in 1881, visitors saw two mounted Beavers and a Prairie Dog donated by Colonel Henry Inman (1837-1899). Inman was a soldier who participated in the US westward expansion and served under George Custer. Inman married Eunice Churchill Dyer (1842–1922), the daughter of a shipbuilder in Portland, Maine in 1862, explaining the connection of Kansas-based Inman to the PSNH.

Beavers are the largest rodents in North America, and although their populations are stable in 2023, people hunted them to near extinction in colonial Maine up to the late 1800s, when Beaver pelts were the most valuable trading item in North America. The loss of Beaver populations meant that their dams no longer maintained ecological balance and growth of plants by controlling runoff, erosion, and floods, causing an imbalance in the rivers.

Beaver fur top hats were popular because they are durable and water resistant. Manufacturers shaved off the animal’s hide, and pounded the inner beaver hair into felt, then steamed, shaped, rolled, pressed, and blocked it into the shape of a hat.

Top hats are a status fashion accessory, associated with wealthy White men wearing tuxedo bow ties and tails. But some Wabanaki people, mostly women, also embraced the fashion. Like other European objects introduced into Indigenous societies, Wabanaki people transformed top hats by adding silver adornment and other elements, making them their own.

Sixth Mass Extinction?

Earth has experienced five mass extinction events, periods of geological time ranging from a few thousand to millions of years, where a high percentage of biodiversity dies out. The last extinction was 65 million years ago, when an asteroid changed the earth’s climate and wiped out Dinosaurs, along with three-quarters of earth’s plant and animal species.

Some scientists say we are in a sixth mass extinction because human activity has altered 75% of the earth’s land surface, degrading water, land, and air. Scientists estimate the current species extinction rate is up to 10,000 times higher than natural extinction rates because of human activity. The World Wildlife Fund calculates between 200 and 2,000 species extinctions occur every year. These rates of population declines and extinctions are high enough to threaten the ecosystems that support human life on earth.

Climate breakdown is happening faster than predicted. The United Nations calls for a 45% cut in emissions by 2030 to avert catastrophic warming. If not, irreversible impacts like melting ice caps, frequent and intense weather events, and massive biodiversity and ecosystem loss will displace almost 3.3 billion people living in vulnerable areas. Humans have caused the critical situation, but we can create potential solutions

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), whose territory once extended into Maine, was once so common people said the sky darkened for days when flocks passed overhead during migrations. Dexter, Maine, was the location where the last reported Passenger Pigeon was shot in 1896. Mainly due to overhunting, Passenger Pigeons became extinct in 1914 when a solitary female bird named “Martha” died at the Cincinnati Zoo.

The Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) was one of four parakeet species in the US, ranging across eastern North America from the Gulf of Mexico to southern Ontario. European colonization cleared Carolina Parakeet old growth forest habitat for agriculture, and farmers shot the birds to stop them from eating crop seed. The fashion industry was responsible for killing thousands of Carolina Parakeets, their bright feathers used on clothing and hats. The last captive Carolina Parakeet died at the Cincinnati Zoo on February 21, 1918, coincidentally in the same cage as Martha, four years earlier. A small population of the birds lived in Florida, after their decline the Carolina Parakeet was declared extinct in 1939.

The Northern Curlew (Numenius borealis) was one of the most common shorebirds in North America, with migration flights to Argentina. Without a confirmed sighting since 1963, the Northern Curlew is considered Critically Endangered or possibly extinct due to overhunting.

Large herds of Woodland Caribou used to roam the old growth forests of Maine, feeding on ground and tree lichen. European settlement, industries like paper making which reduced forests, and over-hunting by non-Indigenous game hunters led to the extinction of Caribou in the state around 1914.

Maine worked to reintroduce Caribou twice in 1963 and 1993, but Maine’s landscape no longer supports Caribou. The young trees don’t produce the correct lichen, versus old growth, and White Tail Deer populations, who carry a brain worm deadly to Caribou, have increased. Listed as an endangered species by the United States in 1984, the Woodland Caribou is one of the most critically endangered mammals in North America. This is a significant loss to Wabanaki people, as stories and ceremonies tied to Caribou have been impacted. One example is the Penobscot 10th moon or month, usually associated with the second half of September and first half of October, is mačewatohkí-kisohs, “moon of rutting moose and caribou.”

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) was the largest Woodpecker in North America with a total length of 19 to 21 inches and a typical wingspan of 30 inches. It got the nickname the Lord God Bird because people would exclaim “Lord God” when they saw it because it was such a stunning bird, visually. The bird only lives in cypress swamps and needs very large tracts of this habitat. As we have changed the landscape through logging and development so there aren’t massive tracts of swamplands in the southern US, the species has (likely) gone extinct.

Pileated Woodpeckers can thrive in smaller areas and can still be found; they are often misidentified as Ivory-billed Woodpeckers.

The US Fish and Wildlife reports the last confirmed sighting as being in 1944 but is reviewing its 2021 decision to declare the bird officially extinct.

Dioramas in bell jar cases became popular in the Victorian era as home decor. Taxidermied animals, which would never exist together in the same ecosystem, put in “fantasy” habitats show how design fads, in addition to fashion, affected bird populations.

The popularity of learning about the natural world, and owning home dioramas were spurred by natural history societies like the PSNH. The PSNH was filled with biological specimens and taxidermy animals. Taxidermy mounts are human reconstructions of formerly living animals, their skin draped over a metal form, stuffed with straw and dusted with pesticides to repel insects, or a flattened flower faded and dried on a herbarium sheet of paper.

Starting in the late 1600s, taxidermists experimented with methods for preserving natural history items. Using wine, gin, rum, brandy or other “spirits” helped to stop mold and insects from damaging the skins, but often removed much of the color. Preservatives became increasingly toxic, with chemicals like arsenic widely used. For these reasons, many collections are sealed in boxes or under glass domes to keep people safe.

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/exhibits/CODERED