(Page 8 of 8) Print Version

Anthropology and Natural History Museums

Anthropology and Sociology, the study of people and societies, were new disciplines in the late 1800s. Their rise dovetailed with the development of natural history museums that displayed non-White peoples, including Indigenous peoples of North and South America, Oceania, Asia, and Africa as frozen in a primitive past and exotic. They placed Indigenous items alongside dinosaur fossils, minerals, and taxidermy wildlife, or miniaturized and minimized them into tiny dioramas.

Anthropologists went into the field on “salvage” collecting trips for museums, presuming that colonialist initiatives, including confining Indigenous peoples to reservations and taking Native children out of the communities and into boarding schools, would result in the acculturation and “extinction” of Indigenous peoples. They removed important cultural items—ancestors—and sometimes the bones and actual Indigenous peoples, without permission.

Museums did further damage by interpreting Indigenous cultures through Euro-American perspectives, silencing Indigenous voices and without engaging descendants, resulting in misrepresentation, othering, and contributing to centuries of societal stereotypes, eugenics policies and sterilization tactics, and governmental programs that continue to harm Indigenous peoples.

PSNH curator Edward S. Morse studied at Harvard with professor of Zoology, Louis Agassiz (1807-1873) starting from 1859 to 1861. Agassiz was a renowned Swiss naturalist who rejected Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Instead, he promoted polygenism, a racist and unfounded theory that proposed different races were separate species. People often used Agassiz’s teachings to justify enslaving Black people. Morse, an ardent supporter of evolutionary theory, broke with Agassiz over this issue.

Arthur Norton spent 35 years as curator for the Portland Society of Natural History. He wrote Mammals of Portland, Maine describing each species in alphabetical order.

Norton included a section about Primates, including a historical sketch of the Wabanaki peoples living in the region, as described by Europeans. The entry is followed, unfortunately, by the next species, Rodentia, and the New England Woodchuck. All humans are mammals and primates. Humans are listed under Great Apes, with a subgroup of Hominins. Norton’s inclusion only of Wabanaki peoples and incorrectly as a separate race (Homo sapiens Americanus) in his chapter on Primates, instead of all humans living in the vicinity of Portland, denies their humanity and makes them a subject of study.

Norton mentions Frank Speck, an anthropologist with the University of Pennsylvania who studied Wabanaki peoples, and collected items through salvage anthropology methods, wrongly thinking their culture was disappearing.

Minik Wallace and the American Museum of Natural History

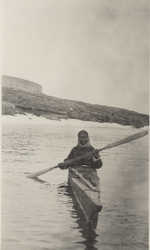

In the summer of 1897, Robert E. Peary sailed to northwestern Greenland to bring an iron meteorite back to the United States. Franz Boas, anthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York asked Peary to invite an Inuit hunter to travel to New York and spend the winter at the museum so Boas could learn about life in the region.

Peary was happy to oblige, but when he returned to New York in the fall he had with him not one man, but three, along with one woman and two children. Tragically, many of the Inuit soon fell ill, and by winter all but one man, Uisaakassak, and one child, Minik, had died of tuberculosis. Uisaakassak returned to Greenland in the spring, but a museum staff member adopted eight-year-old Minik and raised him with their children.

As a teenager, Minik learned that his father’s body had not been buried as he had been told, but had instead been processed, and his bones stored at the museum. Minik embarked on an unsuccessful battle to have his father’s remains returned to him for burial, and then pleaded with Peary to give him passage back to Greenland. Peary refused, but in 1909 Josephine Peary arranged for Minik to go north on a vessel being sent to meet her husband.

Minik struggled at first, having forgotten much of the language and having missed the crucial years of training that other young hunters had. Still, he was able to relearn and become a competent hunter. He did not forget his years in New York and in 1917 arranged to sail south once more. He took a job in a lumber camp in northern New Hampshire, and died there in the fall of 1918, a victim of the influenza pandemic.

Cultural Collections at the Portland Society of Natural History

The PSNH cultural collections included over 500 archaeological items like pre-Columbian pottery and hundreds of cultural materials like Wabanaki baskets. The worldwide cultural items were displayed mixed together, alongside biological and mineral collections.

The Portland Society of Natural History had vast global cultural collections, including Wabanaki items like a Penobscot birch bark canoe and Penobscot root club. Starting in the 1970s, Indigenous peoples in the United States demanded accountability from museums and crafted decolonizing strategies and federal laws as pathways for repatriation of ancestors and sacred items, deep collaborations, and accurate representation.

PSNH staff donated most of the cultural collections to the University of Maine’s Hudson Museum upon closing in 1970. When the PSNH burned in 1866, museums across the nation sent donations to help rebuild the collections. The Smithsonian contributed a cultural “Smithsonian Starter Kit” that included eight items from the Arctic and others from the Pacific, amassed by the US Exploring Expedition from 1838 to the 1850s that mapped and explored the Pacific, Antarctica, and the American Northwest Coast. Individuals added to the PSNH collections from 1866 to 1970.

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/exhibits/CODERED