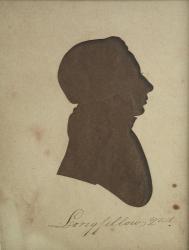

Eighteen-year-old Henry Longfellow graduated in 1825 from Bowdoin College at Brunswick, Maine, only forty miles from his hometown, Portland. The civilizing, if frugal and simple, "country college" (so called by Henry James) recorded graduates' profiles for a "group picture" of a class famed for high-achievers including Nathaniel Hawthorne and Franklin Pierce along with Longfellow. A silhouette artist would cut a portrait in the center of stiff white card paper. India ink brushed over the profile-shaped stencil produced individual small black-on-white copies for friends as well as a large sheet "class portrait." The Bowdoin College Library retains originals of Longfellow's silhouette stencil, ink copies, and the class silhouette record.

See slide 14

Scherenschnitte/Silhouette Lesson Plan

Stephen and Zilpah Longfellow recognized their second son's literary gifts, so they invested both confidence and money in a post-graduate European grand tour for him.

He did not disappoint them, acquiring fluency in French, Spanish, Italian, and German in preparation for an academic career during over three years abroad.

He whimsically verified his hard work when he drew himself in German student garb, studiously reading a book while smoking a pipe with his next door neighbor and traveling companion, Edward Preble, seated at his left with a newspaper.

Now-and-Then Portrait Lesson Plan

Longfellow began his first professorship at his alma mater in 1829, essentially inventing his own curriculum and texts to teach modern languages and comparative literature until Harvard tapped him as Smith Professor of Modern Languages in 1834.

Portrait/miniature artist Thomas Badger established Brunswick ties, too, when he traveled from his Boston home base in 1826 to copy paintings in James Bowdoin III's unusually fine collection, housed as the college's art museum.

Badger profitably rendered some faculty portraits as well, possibly including the 18-year-old post-graduate Longfellow, but more likely returning in 1829 to depict the 22-year-old professor's first sitting for a professional oil portrait.

The painter, a grandson of noted colonial portraitist, Joseph Badger, was born in Reading, Massachusetts, and apprenticed to Alvan Fisher and John Ritto Penniman in Boston. He traveled northern New England regularly to ply his trade, as was the common practice for painters of the time.

Engravers and lithographers worked from paintings or drawings to produce and circulate multiple copies of an image before photography became a viable process around 1839.

Painters in turn often copied from prints for many reasons, not least to learn new fashions, improve their craft, or simply make a living.

Typically, the hard lines of Wilcox's engraving clarify the young professor's academic robes and features, but they also generalize, reducing idiosyncrasies that attest to an artist's first-hand observation of the subject. Notably, too, the printmaker fails to credit Badger as the original source.

Commercial Illustrations Lesson Plan

Portrait of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, ca. 1835

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

In his recently published biography, Longfellow, a Rediscovered Life, Charles Calhoun quotes Elijah Kellogg's remembrance of his childhood friend: "He was a very handsome boy, retiring, without being reserved, there was a frankness about him that won you at once. He looked you square in the face. His eyes were full of expression, and it seemed as though you could look down into them as into a clear spring" (page 22). Maria Röhl's drawing might easily be mistaken for a portrait of Longfellow as the boy Kellogg described, but the popular lady artist rendered the youthful visage of the 28-year-old professor when he visited Europe for a second time as a married man preparing to teach at Harvard. Six weeks after their visit to Röhl's studio, Mary Storer Potter Longfellow suffered a miscarriage, attended at midnight only by her young husband. She never recovered and died quietly in a Rotterdam hotel on November 28, 1835, after only four years of marriage. Traveling the Alps seven months later, her grieving widower met Frances Appleton the nineteen-year-old Bostonian who would eventually become his second wife.

"My acquaintance with our great poet Longfellow began many years ago, and I never went to Cambridge without calling on him in his delightful mansion. My first portrait of Longfellow, painted when he was still young, belongs to his publishers, Messrs. Ticknor and Fields." So wrote George Healy in his 1894 memoir, Reminiscences of a Portrait Painter (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., p. 218), and he seems to have been one of the poet's favorite painters.

'Little Healy' was the eldest son of an Irish seaman, born in Boston and nudged toward portraiture during adolescence by his maternal grandmother, by master artist, Thomas Sully, and by social lioness, Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis.

See Slide 30

1966 copy print of a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow portrait, 1839

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Longfellow settled into an eighteen-year career as Smith Professor of Modern Languages and Belles Lettres at Harvard in the fall of 1836, with a widely read book of prose, Outre-Mer (1831), to his credit and all his books of poetry before him.

Voices of the Night (1839) presented his first major collection of poems, half of them written in rooms rented from an eccentric widow, Elizabeth Craigie, at 105 Brattle Street, Cambridge.

He sat that year for a Wilhelm Franquinet drawing and wrote to his father on November 10, 1839, "Franquinet has great skill. He took my face for friendship's sake, in crayon: exceedingly like. He has since used it as a duck-decoy in Boston, and has his hands full so striking do they find my likeness."

The sketch generated numerous reproductions and linked a face to the poetry that cultivated new celebrity, undoubtedly to the surprise of both artist and writer.

(Quote is from archive record 4432, Longfellow National Historic Site/Craigie House)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow by Franquinet, 1839

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Franquinet drew two more rather less flattering sketches of Longfellow, working either from the image drawn from life or from memory.

Printers redrew variations of the three to publicize the up-and-coming American poet in magazines, newspaper clippings, and books.

The Craigie House archive owns Franquinet's not-from-life pair of portraits; Bowdoin Library, Maine Historical Society, and Craigie House own several copies of the derived prints.

A lithograph signed 'Franquinet' and dated 1842 extended the original bust-length view of Longfellow to more-or-less full figure, inventing arms, legs, and a chair.

The signature suggests that Wilhelm Hendrik Franquinet himself drew this widely distributed print for the May 1843, issue of Graham's Magazine."

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1843

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Yet another derivative was worked up from the Graham print, omitting the full figure and chair and using softer edges and powdery shading, like an etching, although the text indicates that it's another lithograph.

Accuracy of likeness and proportions suffer obviously with each removal from the live sitter, not unlike modern photocopy clones, and so does the work's bearings with the original artist.

See slide 4

It is reasonable to speculate that Ann Hall painted her 1845 miniature of Longfellow while looking at a Franquinet print, not the poet.

The awkward image implies an overextension of her tendency to idealize: working from a print and not a live subject, she rendered the middle-age poet as a pudgy boy.

Hall was nonetheless an important New England miniaturist, born in Pomfret, Connecticut, trained in Newport and New York City.

Her little ivory in conjunction with the extensive series of Franquinet-based prints indicate two cultural phenomena. One, Longfellow's popularity grew quickly, and, two, print technology nursed a new demand for celebrity pictures.

Portrait of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1840

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

The popularity of the widowed professor's poetry increased with each new publication, some of which expressed his grief not only for his deceased wife, but also for Fanny Appleton's dismissals of his affection for--and proposals to-- her.

A distant cousin related through the Wadsworths, C. G. Thompson captured the handsome bachelor's loneliness in an intense, romantic oil portrait.

Fanny Appleton may have been immune, but Schoff's widely disseminated print of Thompson's pensive image may well have caused a flutter in many feminine hearts and increased book sales accordingly.

Schoff created a number of print images of the poet.

See Slides 25 and 31

French silhouette artist M. August Edouart came to the United States in 1839 and stayed for ten years, cutting and collecting over 9,000 "double papers" of "distinguished Americans, statesmen, journalists, men of letters, and heads of families," keeping one for himself, giving the other to the sitter.

His profile shows a dapper Longfellow. (Quoted from unidentified journal clipping HWL Col., M112.5.1, b.4, f6)

See slide 1

See Scherenschnitte/Silhouette Lesson Plan

World Wide Art Resources: Augustin Edouart

Frances Appleton's fortune and social position far exceeded her scholarly suitor's, but after seven years of rejection, she summoned Mr. Longfellow to her Beacon Street home on May 10, 1843, to accept his marriage proposal. She handled the social differences of her Portland in-laws tactfully and paired ideally with her literary husband. Possibly during a wedding-related trip to Maine that nuptial year, local master Charles Octavius Cole took Longfellow's portrait. Cole came to Portland to study with the town's first settled professional painter, Charles Codman. He stayed, and his "buttery" style became the favorite of the town’s leading citizens in the 1830s. He helped establish Portland's early reputation as an art community.

Sketch of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1844

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Seth Cheney's small, delicate portrait takes ten years off his subject’s true age of thirty-six, though a happy marriage may well have been the real clock-stopper. Fanny Longfellow's father purchased the Craigie mansion for the couple, children increased the family quickly, and then poet’s career flourished beyond expectations. Cheney's sketch was drawn for commercial purposes, to be used specifically as a template for a print. Interestingly, it was drawn on a scrap paper; the portrait of an unidentified dark-haired girl already marked the back side of the sheet.

Cheney's print presented the poet as America's dignified, youthful rising star of poetry, as indeed he was. Another variation of the image omits the "halo" of shadow behind the head.

Matthew Brady's portrait of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1859

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

Between 1844 and 1855, six children were born to the Longfellows, and five survived to adulthood. The professor and his young family had their photographs taken often, starting in the early days when the medium’s artistic and commercial viability was in question. Appearing less romantic than in the Thompson painting and more obviously marked by time than in the Cheney prints, photos from the period present Longfellow as a prosperous and contented family man.

Portrait of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow by Eastman Johnson, 1846

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Patronizing a promising fellow Mainer, Longfellow invited artist Eastman Johnson to portray eleven of his family members and best friends in Cambridge during the fall of 1846.

Drawings made included himself, his two sons, his sisters, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph W. Emerson, and Charles Sumner. Several of the drawings still hang in the study and parlor of the Craigie House.

Johnson studied art in Düsseldorf in 1849 and learned an attention to 'detail, accurate drawing, elaborate finish, and easily understood subject matter' that transformed him a virtuoso genre painter. (Quote from Matthew Baigell, A Concise History of American Painting and Sculpture, (USA: Icon Editions, 1996), p. 80; see also p. 132.)

S. W. Smith's print turned Johnson's Longfellow drawing into the epitome of a Brahmin, and more-- a middle-aged man in thoughtful control of his faculties and prosperity, a fit leader of national culture.

Like many women of her class, Fanny Longfellow tried her hand at drawing. Unlike professionals' vaunted interpretations of her husband, she produced a gentle, personal contour drawing with a mood of contented domesticity, a peep at a bemused husband posing patiently for his wife's sketch.

Portrait of Papa, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, ca. 1852

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

The poet posed just as patiently for his children's sketches and, except for the muttonchops and frock coat, this Longfellow child's drawing of Papa would fit right into any third-grade art class today.

Portrait of Papa, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1852

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

The second Longfellow son, Ernest, grew up to become an unremarkable professional artist, considered rather stuffy and unconventional.

Three large oil portraits of his aged father executed in the 1870s comprise his best-remembered work, but Papa was already a subject for his pencil at age seven.

See slides 33 and 34

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow by Francis Alexander, 1852

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Oliver Wendell Holmes claimed that "he trembled every time he drove past the Craigie House, for those who lived there had their happiness so perfect that no change, of all the changes that must come to them, could fail to be for the worse" (quoted by Charles Calhoun in Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life, Boston: Beacon Press, 2004, p. 198).

Francis Alexander's portrait captures the rich depths that colored his sitter's life in the 1850s, possibly as his own star was sinking.

The Connecticut-born artist studied with Gilbert Stuart, traveled to Italy more than once, and won mention in William Dunlap's first American art history book, yet is not well known today.

Portrait of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1852

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Steven Alonso Schoff was a premier engraver and etcher of his time, creating bank notes as well as portraits. He trained in New England, New York, and Paris.

Schoff expertly transformed many soft-edged paintings and drawings of Longfellow into the hard lines of commercial prints without losing the spirit of the original work.

He produced, for example, an etching that maintained the loose style of pastel and captured Alexander's sense of the rumpled intellectual. Though unsigned, the frontispiece to Samuel Longfellow's 1891 Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, vol. II, is probably Schoff's work.

Compare it to his signed 1862 engraving of a somber Longfellow after C.P.A. Healy's oil portrait.

See slide 31

150 Years of Print Collecting at the Smithsonian

Portrait of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Cambridge, 1854

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

London publisher George Routledge sent his illustrator, Samuel Laurence, overseas to make a drawing for an engraving of Longfellow in 1854.

It took a week to complete the assignment, and the poet's family considered the lively picture the closest likeness ever taken.

Now-and-Then Portraits lesson plan

Fine as it is, Wilcox's engraving does not reproduce the vigor of Laurence's drawing, an energy which the poet doubtless emanated in one of his headiest years.

By 1854, Longfellow's fame rivaled that of other international celebrities, many of whom he counted as friends, such as Charles Dickens, Jenny Lind, and Fanny Kimble.

Earnings from his books were sufficient to prompt a decision to retire from his Harvard professorship. He devoted his powers completely to writing and translating and gracefully meeting the regular troupe of devotees who showed up at his door.

Commericial Illustrations Lesson Plan

Professor William C. Watterson of Bowdoin's current English Department tells the story of a rare surprise. In late fall, 1985, he sauntered up a staircase at Childs Gallery in Boston and "stumbled across what I think is a very fine small painting of Longfellow."

His November 5 letter to College President A. LeRoy Greason (from which the quote comes) resulted ultimately in the Bowdoin College Museum of Art acquiring the portrait, bringing to three their collection of Longfellow paintings.

See slides 30 and 34

Bowdoin also acquired an engraving of Thomas Read's 1859 Longfellow portrait with a plain, flat background, labeled "ON STEEL BY JOHN SARTAIN--AFTER THE OBJECT BY J B READ--THE ORIGINAL IN THE POSSESSION OF FRED T DRIER ESQ."

Read was a roaming Pennsylvanian who studied painting in Ohio, the Northeast, and Europe before settling down in Philadelphia.

Starting in 1845 as a Longfellow "protégé," he painted the poet on several occasions. Perhaps most significantly, he produced the famous group portrait of the three sweet little blonde Longfellow daughters that became a sentimental print icon of childhood before the Civil War. It still hangs in the Craigie House.

Bowdoin College received the fine, austere portrait that G. P. A. Healy created for Longfellow's publisher, James T. Fields, as a bequest from Mrs. Annie Louise Cary Raymond after her own patient thirty-year wait to acquire it.

George Healy knew the poet for many years, painting him at least three times and portraying Mrs. Longfellow and her sister as well.

The vigorous but stoic image of a rapidly aging gray-beard was dated May 19, 1862, only nine months after his wife's tragic death.

A match onto Fanny Longfellow's gauzy, hoop-skirted summer dress severely burned her torso and lower body, though not her face. She died calmly in own bed the next morning, July 10, 1861, leaving five children aged five to seventeen in the care of their famous father.

See slide 6

Now-and-Then Portrait Lesson Plan

Portrait of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1862

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Schoff's engraving of the 1862 Healy painting present Longfellow as a sober, less approachable celebrity.

Healy painted the poet once more in 1870, depicting the "splendid-looking man, with perfectly white hair and beard---eyes bright and expressive--with one of his daughters, a very young girl with golden hair."

Recounting his exchanges with the Longfellows on their Roman holiday, the artist does not mention that he worked from a photo, placing the pair in front of the well-known classical arch without seeing them there.

Their visit produced a rather more interesting work from Healy after he introduced the poet to the musician, Franz Liszt: "The characteristic head, with the long iron-gray hair, the sharp-cut features and piercing dark eyes, the tall, lank body draped in the priestly garb, formed so striking a picture that Mr. Longfellow exclaimed under his breath: "Mr Healy, you must paint that for me!" So he did. (Quotes are from Healy's memoir, pp. 219, 220; double portrait reproduced on p. 218)

See slide 25

Longfellow's physical appearance changed rapidly after his wife’s death, with first with growing a beard, then with his hair turning white almost overnight. At sixty-one, just seven years after Fanny's tragedy, the eccentric London photographer Julia Cameron dramatically presented the American writer with the aging majesty of a Shakespearean character. Various artists tried to recreate the noble endurance of her image in paint and print. William Merritt Chase, for example, copied Cameron for an etching at Ernest Longfellow's request and possibly for a painting. The dramatic pose appealed to many unidentified printmakers, including an engraver who published a mundane version in McGee's Illustrated Weekly, vol. III, No. 26, May 18, 1878. (Bowdoin College Library’s Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Collection contains clippings of the two prints and photos of the painting in M112.5.1 Box 4, Folder 26.)

Now-and-Then Portrait Lesson Plan

Commercial Illustrations Lesson Plan

Painting of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1876

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Ernest Longfellow pursued an undistinguished art career in adulthood, but he painted three portraits of his father toward the end of his life.

"Erny" recalls in his 1922 autobiography, that "In that spring (1876), before leaving for Europe, I painted a portrait of my father which the family thinks the best portrait of him ever taken. I am not very pleased with it myself, and think the one I painted on a commission for Bowdoin College after studying with Couture better."

Erny was 31 that year, and his papa was 69. (Quoted from Museum Catalog Record 4629, Craigie House/Longfellow National Historic Site.)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow died March 24, 1882, after months of struggling with a stomach sickness, possibly cancer, and he was buried next to both his wives in beautiful Mt. Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge.

Charles Calhoun points out the irony of the speedy evaporation of the poet's "substantial reputation" following such a celebrated life and posthumous tributes that included the installment of a bronze portrait bust by Thomas Brock in Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey. Longfellow was only American poet so honored.

The public irony may obscure a private one, as the great man sat for a final portrait from life by his own son.

Ernest was able to compare the merits of the completed 1881 Bowdoin commission relative to his 1876 painting despite his loss, doubtless because he needed to pursue his own course as an artist, just as his father had, whether or not he reached the same peaks.

Three regional museums collect and display portraits of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

-The Wadsworth-Longfellow House, 489 Congress Street, Portland, Maine 04101, operated by Maine Historical Society. Their collection includes three paintings as well as photos, prints, and sculptures.

Maine Memory Network

-The Craigie House/Longfellow National Historic Site, 105 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, operated by the National Park Service. The house museum displays eight original drawings and paintings of the poet, as well as photographs and four marble busts. The archive stores another painted portrait, several drawings, including Longfellow children's drawings of their papa, approximately sixty prints based on original portraits, and hundreds of photographs.

Longfellow National Historic Site website

-The Bowdoin College Library and Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine 04011. The library displays an oil portrait of their illustrious 1825 graduate and professor, and the museum displays two more. The library's Special Collections conserves the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow collection with more than fifty-five prints, photos, silhouettes, and clippings of the poet's image.

Bowdoin College Library

Longfellow Collection at Bowdoin College Library

This slide show samples from these institutions' extensive collections with regard to a primary theme:

-Contrast original 2-D images (paintings, drawings, photos, cut silhouettes) with their commercially replicated print versions (engravings, lithographs, inked silhouettes), with special attention to artists' interpretations of the poet's personality

The show suggests three additional themes for contemplation or discussion as well:

-Examine the famous man's aging process and biography through his changing appearance

-Observe changes in the technology of producing nineteenth century portraits demonstrated in commercial printmaking and photography, and link them to changing cultural mores

-Identify some of the more or less obscure artists trying to earn a living through portraiture in New England during Longfellow's lifetime

Sources:

Bowdoin College Library, George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Collection, M112.5.1, Box 4

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Maine Memory Network, www.mainememory.net

The Maine Historical Society and Wadsworth/Longfellow House

National Park Service, Longfellow National Historic Site/Craigie House and archives

Baigell, Matthew. A Concise History of American Painting and Sculpture. rev. ed. New York: Icon Editions, 1996.

Brommer, Gerald F. Discovering Art History. 2nd ed. Worcester: Davis Publications, 1988.

Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004.

Strickler, Susan E. <span class= "book_title">American Portrait Miniatures: The Worcester Art Museum Collection. Worcester: Worcester Art Museum, 1989.</span>

----------

Sydney Smith's quote was published in The Edinburgh Review vol. 3, January, 1820, completely as:

"In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book, or goes to an American play, or looks at an American picture or sculpture?"