The area that came to be known as Acadia generally encompassed the parts of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Northeastern Maine on the Bay of Fundy.

This map, Nouvelle Ecossee ou Partie oriental du canada, was printed in 1756 by Georhe-Louis Le Rouge of Paris.

What is going on in this image?

What do you see that makes you say that?

What more can you find?

This portrait shows Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ca. 1846. Born in Portland in 1807 to Zilpah (Wadsworth) and Stephen (IV) Longfellow, he was the second of eight children. Longfellow published his first poem, "The Battle of Lovell's Pond" at age 13 in the Portland Gazette, without his last name attached. He was accepted to Bowdoin College in Brunswick the following year and graduated in 1825, along with his older brother, Stephen.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) and Trap (dog) portrait, 1865

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Longfellow today is more commonly recognized by portraits taken later in his life. This photograph was taken ca. 1864, and features the beloved family dog, Trap.

Longfellow became Bowdoin's professor of modern language in 1826, and began teaching after three years abroad in Europe.

Longfellow married his first wife, Mary Storer Potter, in 1834. Mary died the following year during a trip to Europe due to complications from a miscarriage.

Frances Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow, 1834

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Longfellow married his second wife, Frances Elizabeth (Fanny) Appleton of Boston, in 1843 after a long courtship.

Henry, Frances, Charles and Ernest Longfellow, 1849

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Henry and Fanny Longfellow had six children, five of whom survived infancy.

Fanny died tragically in 1861 after her dress caught fire in a household accident. Longfellow's signature beard, seen in photos from the 1860s to the end of his life, was likely grown in to hide burn scars he sustained while attempting to put out the fire.

Longfellow spent a significant amount of time in Maine, writing some of his poems in his childhood home in Portland.

Longfellow National Historic Site, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1990

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Longfellow's primary residence with his wife and children was Craigie House in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Most of Longfellow's poems were published out of Boston.

Silhouettes of the Famous Class of 1825, Bowdoin College, ca. 1825

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

One of Longfellow's contemporaries, and fellow 1825 Bowdoin graduate, was author Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Hawthorne was the author of historical novels such as "The House of the Seven Gables" (1851) and "The Scarlet Letter" (1850), both of which were dark romances set in Puritan New England.

Why were nineteenth-century American authors interested in writing about events in America's short history?

Hawthorne's friend, the Reverend Horace Connelly, was invited to a dinner with Hawthorne and Longfellow in 1840, where he told the story of two Acadian lovers separated by the deportation ordered by the British in 1755.

Reverend Connelly optioned the story to Hawthorne first, for a novel. When Hawthorne declined, Longfellow asked his permission to turn the idea into an epic poem instead, which Hawthorne permitted.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Cambridge, ca. 1872

Item Contributed by

NPS, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

Why epic poetry?

"Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie" is written in dactylic hexameter, the style of classical European epics such as Homer's "Illiad."

Longfellow was familiar with the style as well as European languages, literature, and poetry. He would later publish (in 1867) the first English translation of Dante Alighieri's "Inferno" (Italian, 1314) in blank verse.

Longfellow's contribution to American poetry and literature was the development of mythopoetic figures into the cultural consciousness, and thus the creation of new American mythology.

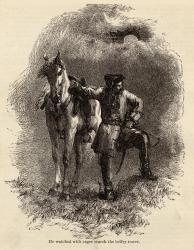

Illustration to accompany the poem The Courtship of Miles Standish, ca. 1880

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

Longfellow's epic poem "The Courtship of Miles Standish" (1855) followed "Evangeline" as a work based on New England history. Priscilla Mullins and John Alden, Mayflower pilgrims featured in the poem, were maternal ancestors of Longfellow's.

One of Longfellow's best-known epic poems is "The Tale of Hiawatha" (1858). "Hiawatha" is not based on Wabanaki oral tradition, but Longfellow wrote about Native subjects with some frequency. While "Hiawatha" is a Romantic poem for a primarily white Anglo audience, the story brought a Native hero into the Victorian public consciousness.

Longfellow's poems collected in "Tales of a Wayside Inn" were written between 1853-1863. This image comes from "The Saga of King Olaf," which draws its subject matter from the Eddas of Norse mythology.

Another of Longfellow's most recognized poems is "Paul Revere's Ride," from "Tales of a Wayside Inn," which gave rise to Revere's legacy as a mythopoetic figure.

Transcription

Paul Revere Bell Commissioned for Thomaston Meeting House, 1797

Item Contributed by

The General Henry Knox Museum

The real Paul Revere was a silversmith - General Henry Knox commissioned this bell from him for the Thomaston (ME) Meeting House, 1797. Revere is arguably more recognizable today from Longfellow's poem than from his silver work.

What do we think we know about Paul Revere from Longfellow's poem?

Why do we remember Longfellow's version of him?

Figure de la Terre Neuve, grande riviere de Canada, et cotes de l'ocean en la Nouvelle France, 1618

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

The historic Acadia, or Acadie, was a region in the Bay of Fundy settled by immigrants from west-central France in the early 1600s. Most of the Acadians were peasant farmers (laboreurs), who may likely have left France due to any combination of Protestant-Catholic religions tensions and violence, disease, and famine.

This map, Figure de la Terre Neuve, grande riviere de Canada, et cotes de l'ocean en la Nouvelle France, was created by Marc Lescarbot during a 1607 expedition, and printed in 1618. Note that the European settlements are marked with a cross.

The Acadians brought to their new settlements the same style of wetland agriculture they had developed in west-central France. This type of agriculture translated well into the marshland regions of New Brunswick and Northern Maine.

These wooden shoes, or sabots, show the type of Acadian footwear worn when working outside and particularly when people were harvesting salt hay from the high marsh grassland region of the intertidal zones along the Maine coast.

Salt hay, when mixed with upland hay, provided cattle with salt and other necessary nutrients to produce healthier livestock.

Many of the people who became Acadians fled France due to anti-Catholic animosity. England was a primarily Protestant power, and parts of France were becoming Protestant as well. The majority of the French people held onto their Catholic heritage and religious identity.

This Acadian baptism certificate was printed in Paris and depicts Catholic imagery in honor of the baptism of Marie-Anne Berebe in 1913. Today, Acadian descendants continue to hold onto their Catholic heritage.

Samuel de Champlain is credited as the founder of Acadia in 1604. He was not the only explorer to "discover" the land at that time, however - Pierre Dugua, Sieur du Monts, was the leader of the first expedition to the region.

Dugua, however, was Protestant, while Champlain was Catholic.

Why was it important to the Acadians that their region's founder be Catholic?

The religious aspects of "Evangeline" were later embraced by people in the Acadian diaspora.

Take another look at this image from earlier - it depicts a scene of the exile, or "le Grand Derangement," of 1755, specifically showing the character of Evangeline leaving her home. It comes from an illustrated edition of the epic poem by J.P. Davis & Speer, 1880.

What are some important Acadian elements you notice in the illustration?

Le Grand Derangement is only one example of English and French conflict in North America. The Northeast border between Maine, Quebec, and New Brunswick was contested for decades. This map was originally produced in 1755, the year of le Grand Derangement, but was reprinted nearly a century later when American and Canadian interests were trying to agree upon a continental border.

This March 2, 1760 article of submission professes Acadian allegiance to the British.

England assumed rule over Acadia following the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), which ended the War of Spanish Succession. English and French powers alike feared the Spanish rising as the dominant European power, and the English also feared France rising to that same status.

As a result of the Treaty of Utrecht, Acadians became subjects of the English crown. The Acadians, however, tried to remain neutral, not wanting to be caught between either French or English interests. Some individual Acadians allied with one side or the other, but the group as a whole attempted neutrality. Acadie/Acadia had been its own country for more than a century; allegiance to France had faded as Acadians developed their own culture.

Transcription

For decades after le Grand Derangement and the dividing of English and French territories in Canada, the Northeastern border was contested. After the American Revolution, territories were being contested by three dominant Western powers: America, England, and France.

This map shows the potential boundary line between Maine and New Brunswick in 1817. Maine would become the 23rd state, separating from Massachusetts, in 1820.

Champlain map copy, Saint Croix or Bone Island, ca. 1799

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

This map is a ca. 1799 copy of one created by Samuel de Champlain in 1613. Historic maps were often used by later cartographers to determine borders. This map also served as a significant source of information with regard to Jay's Treaty in 1794. Note the information Champlain includes about the Wabanaki homes.

Plan of the British and American positions, Aroostook War, 1843

Item Contributed by

Maine State Museum

The "Aroostook War," during which there were no casualties, was the boiling point for Northeastern boundary disputes. This map shows British and American positions in the early 1840s.

British Foreign Secretary Alexander Baring, Lord Ashburton, was the British designee for signing the treaty that ended the Aroostook war and determined the Northeastern boundary.

Daniel Webster, Secretary of State to President John Tyler, was the American signor of the treaty determining the Northeastern border. Known as the Treaty of Washington or the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, this document was the final determination of the border between Maine and New Brunswick, but also helped to define the American-Canadian border at the Provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

New Brunswick Treaty of Washington anniversary proclamation, 1992

Item Contributed by

Fort Kent Historical Society

This 1992 Proclamation was printed to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the treaty of Washington/Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

The border between Maine and New Brunswick is generally identified by the St. John River. This 1843 map by prolific cartographer Moses Greenleaf shows the State of Maine (with 12 counties) and the Province of New Brunswick. Today, Maine has 16 counties in total, with Aroostook County, which shares the border with New Brunswick, being the largest.

An international bridge over the St. John River between Madawaska, Maine, and Edmunston, New Brunswick, was constructed between 1920-1921, with updates planned to begin in 2021.

The displacement of the Acadians was only one expulsion that has affected the course of Maine history. Displacements in Maine and New England history have often gone hand-in-hand with xenophobia and racism. One such displacement was the expulsion of residents from Malaga Island, off of Phippsburg and Harpswell, in 1912.

Malaga Island was first settled by non-Natives in 1794 by African American mariner Benjamin Darling and his (likely white) wife. It then grew over the 19th century as a small community of white, black, and mixed-race households. Many of the men worked as fishermen in the area.

As tourism increased in Maine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Malaga Island was seen as an eyesore that no town wanted to claim. Its residents were made to leave in 1912 following an order from Governor Plaisted, who curiously had, earlier that same year, promised that the residents would not have to move.

Prior to the expulsion, the cemetery had been exhumed and the bodies reburied at the Maine School for the Feeble-Minded, where several islanders were also institutionalized and sterilized. The motives for clearing the island and displacing residents was not only fueled by the tourism industry, but by public belief in eugenics: the belief that some genetic traits were superior to others, and that "dangers" to the status quo should be sterilized or eliminated; such a belief often targeted people who were poor, mentally ill or neurodivergent, and/or not white.

Maine Governor Baldacci offered an apology in 2010. He was the first Maine Governor to visit the island after Plaisted.

St Peter's School, Lewiston, Class of 1910

Item Contributed by

Franco-American Collection, University of Southern Maine Libraries

Xenophobia fueled other issues throughout the 20th century, particularly against immigrants. French-Canadians hailing from Quebec, though not Acadian, were also victims of Anglo-American Francophobia.

This image shows St. Peter's School in Lewiston, part of the Little Canada community, which taught its students primarily in French. However, as the flag in the background shows, there was pressure for newcomers to be "Americanized."

French was later forbidden from being spoken in Maine schools, except as a foreign language - only the French spoken in France was taught, and not the regional French spoken by Quebecois or the French spoken by Acadians. Some Franco-American families stopped teaching French to their children.

French, and Franco-American identities, were later reclaimed during movements in the latter half of the 20th century.

Americanization class, Boys Club, Portland, 1923

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society/MaineToday Media

Americanization spread across all communities in the early 20th century, particularly in the wake of World War I, when anti-immigrant sentiment was high throughout the United States.

This photo shows an Americanization class from 1923 in Portland, providing immersion classes for students of various backgrounds.

Some people choose not to discuss "difficult" events in Maine history. Should we continue to talk about them? What can we learn from them? Why are these events important not just to the descendants of the communities that were displaced, but to everyone?

How have Acadians shown resilience and kept their traditions alive?

Acadians today live throughout the world, though the primary communities in North America can be found in New Brunswick, northern Maine, Louisiana, and Texas.

The popularity of "Evangeline" helped many Acadians connect with their heritage, and the character of Evangeline became a cultural heroine, with dedicated historic sites in her honor in Grand Pre, New Brunswick, and St Martinsville, Louisiana. Acadian cultural sites are dedicated throughout Northern Maine; the University of Maine at Fort Kent is home to the Acadian Archives.

This engraving of Evangeline, by James Faed, was created ca. 1854, and was purportedly Longfellow's favorite illustration of the heroine. The engraving sits in the Wadsworth-Longfellow House in Portland.

Longfellow was not an Acadian himself, and he made up much of the landscape of Grand Pre, Evangeline's home, basing it more on the landscape he recognized as "Maine" from living in Portland. However, his poem has had an enormous effect on the public in terms of telling the Acadians' story, as well as on the Acadian community over time.

"Evangeline" has been adapted into multiple formats and inspired additional books since its original publication in 1847. The general public was captivated by the love story at the center of the poem, while the Acadian community appreciated the newfound public interest in their cultural history. The first printing of "Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie" sold out quickly, as did the 5 additional printings that followed in its first year of publication.

This image shows a theatre program for a 1902 stage production of "Evangeline." The story was also adapted into two major feature silent films, in 1922 and 1929. The 1929 film starred popular actress Dolores Del Rio as the titular heroine.

An adaptation of the "Evangeline" story entitled "Acadian Reminiscences: The True Story of Evangeline" was published by Louisiana Judge Felix Vorhees in 1907, with several of its elements taken for some time as fact in Louisiana, and particularly St. Martinville, the location of the "Evangeline Oak," where supposedly separated lovers Evangeline and Gabriel met again, only for Evangeline to discover, in the Voorhees version, that Gabriel has found a new love.

Transcription

The popularity of "Evangeline" sparked a wave of consumer goods and collectibles, as well. In addition to illustrated editions of the epic poem, items such as this calendar were printed for public consumption.

The front image for this 1904 calendar shows an early scene from the poem, in which Evangeline prepares for her wedding.

This mid-20th century Evangeline doll shows the enduring interest in Longfellow's poem more than a century after its publication. Note the similarities in the doll's traditional Acadian dress to the 19th century illustrations of the heroine and other Acadian women, as described in the poem.

Why might it be important for an Acadian child to know the story of Evangeline?

The Acadian community enjoyed a cultural revitalization in the latter half of the 19th century as more of the public became interested in the history of le Grand Derangement following the popularity of "Evangeline." It was not Longfellow's intention to spark interest in the event itself; his primary focus was on the story of enduring love, and he had not foreseen the additional outcomes of the work that truly launched his career as a poet.

The Acadian flag, shown here, was adopted by the Acadian community in 1884, following its 1883 design by Father Marcel-Francois Richard and sewn by Marie Babineau. The Acadian flag shows homage to France, while the star represents the Acadian patron saint, the Virgin Mary (Notre Dame de l'Assomption), who guided the Acadians through their suffering. A version with a Fleur-de-lis instead of the star is often seen in Louisiana to represent the Acadian/Cajun community. Maine Acadians did not accept the flag for some time, but it now flies on buildings throughout the state.

Grand Pre remains a pilgrimage site for hundreds of Acadians today.