St. Leon merchant ship, Castine, 1835

Maine Historical Society

Maine Goes Global

In the middle of the 1800s, Maine stood at the juncture of two great streams of commerce: the transatlantic trade with Europe, and the long-shore links between northern and southern states and the West Indies. Maine built the ships that carried this trade and provided the crews that made America the world's premier trading nation. At its peak, Maine shipyards produced more than one-third of the nation's shipping, including some of the finest square-rigged vessels ever built.

Maine's shipyards were well positioned to benefit from America's burgeoning seaborne trade. Numerous sheltered harbors offered sloping beaches suited to sliding finished ships off the ways, rivers carried ocean-going vessels deep into the interior, and forests supplied a diverse array of timber to meet all ship-building needs. No less important, Maine's maritime skills were honed by a seafaring tradition going back to colonial times. These advantages gave Maine's seacoast towns a cosmopolitan air; villagers made friends around the world and knew intimately the goings-on in exotic places like Singapore and Sao Paulo.

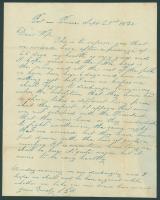

Capt. John Dillingham letter from Port au Prince, Haiti, 1845

Maine Historical Society

Responding to the rise of cotton textile mills in England and New England, Maine shipyards produced deep-hulled square-rigged ships to transport cotton from the South. Expansion of the China trade in the 1840s created a market for clipper ships, capable of quick passage over vast expanses of open ocean.

Sacrificing cargo space and seaworthiness, these sharp-bowed, narrow-beam vessels emphasized speed to carry low-bulk, high-value items and outrun pirates in the South Pacific. They traded opium for Chinese jade, silks, porcelain, brocades, and tea and brought coffee, spices, and other exotics from the South Pacific.

During the gold rush, clippers transported prospectors and equipment to San Francisco and carried mail and passengers in the transatlantic packet service. These maritime activities shaped the culture of the coast. Sea shanties enlivened Maine lore with stories of lost vessels and rapid crossings, and seaborne superstitions made their way landward.

Small-boat building flourished along the coast, each locale producing its own distinctive design. With men away on voyages, women sustained these coastal communities, building networks of support to compensate for the difficulties families faced in this dangerous occupation. Marriage links forged shipbuilding and sailing dynasties that pooled capital and shared risks; sons-in-law became mates and masters in family ships, and daughters inherited vessel shares and combined them with those of their husbands.

Signals at the Portland Observatory, 1846

Maine Historical Society

In Searsport, a major seafaring center, about half the wives went to sea with their captain-husbands, sometimes bearing, raising, and educating their children at sea. Maria Whall Waterhouse took command of the S.F. Hersey in Melbourne when her husband died, and according to legend faced down a mutiny with the aid of her late husband's two pistols and the ship's cook.

Maine's long, indented coast also gave rise to a vigorous fishing industry. The Gulf of Maine was among the world's most productive fisheries, benefitting from a rich mix of nutrients from the Labrador Current and Gulf Stream and from extensive breeding grounds in the bays and estuaries along the coast.

Baiting and hauling lines and cleaning and curing the catch was a round-the-clock business, but by law, crews were awarded equal shares in the profits, because the U.S. Treasury provided subsidies in order to foster seafaring skills for the Navy. Because crews were often members of an extended family, fishing was more democratic than seafaring industries like shipping and whaling.

Maine, close to the great cod fisheries on the Grand and Georges banks focused on cod exports. Salted cod was marketed among urban immigrants and slaves on sugar, rice, and cotton plantations. At its peak, Maine provided one-fifth of the fish product produced in America, a vital source of protein for the nation.

Herring weir at Sandy Island, Eastport, ca. 1887

Maine Historical Society

When competition from larger ports made cod fishing less profitable, Maine fishermen turned to mackerel and menhaden, which arrived in huge schools each spring and were rendered as oil or fertilizer in small factories along the coast. Those markets declined in the 1880s, replaced largely by herring, which was caught in brush weirs along the coast.

Herring were smoked, pickled, used as bait, and, in the 1870s, canned in large processing factories as sardines. Capital investments were low, requiring only a few dories to dip herring out of the weirs and a small schooner to carry them to the canneries.