An Industrial Alternative

Maine's cultural identity was shaped by rural pursuits like lumbering, quarrying, and fishing, but in the first half of the century another landscape was shaping up in cities like Saco, Portland, and Lewiston. Maine experienced the Industrial Revolution in a variety of ways, from home and backyard shops producing tinware, cloth, candlesticks, spoons, chairs, and other items to some of the largest textile factories in New England.

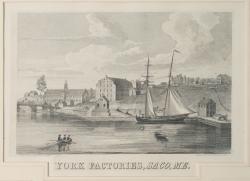

York Factories, Saco, 1830, 1830

Dyer Library/Saco Museum

As in other industrializing parts of the Northeast, when textile mills began turning out spun thread, women wove it into cloth in their homes, and when the mills began producing finished cloth, homebound women sewed it into ready-made clothing. From these amazingly productive homes, sheds, and dooryards came barrel and box staves, wheels and wagons, shoes, straw hats, boots, and myriad other "industrial" products.

Maine's advantage was its huge waterpower potential and its nearby port facilities. Boston supplied the capital and Maine the industrial energy. In 1826, two years after it built the large textile mills at Lowell, Massachusetts, the Boston Manufacturing Company completed a mill twice the size of Lowell at Saco Falls.

The Saco Manufacturing Company, by far the largest single cotton mill in country, burned in 1830 and was rebuilt on a much smaller scale, but from these beginnings the industry spread into central Maine. The power of the Saco River was matched by that of the Androscoggin.

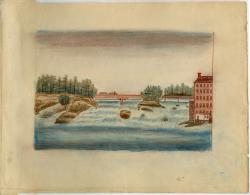

Sketch of Androscoggin River, ca. 1830

Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library

Situated at the Falls of the Androscoggin, Lewiston was destined to become Maine's largest textile center. In 1845 several local investors incorporated the Lewiston Falls Cotton Mill Company, dammed the river, dug canals, and two years later sold their investment to Benjamin E. Bates, a member of the Boston Associates.

Bates opened a new mill in 1850 and added another in 1854. During the Civil War he expanded again, sending agents out into the countryside to recruit women. The company's boarding houses along Canal Street were pleasant, inexpensive, and strictly monitored, and, as in Lowell and other textile centers, Yankee women lived and labored until Irish immigrants replaced them.

Families from Ireland had been settling in Maine since colonial times, but the potato famine of 1845-1851 triggered a dramatic increase in migration. Impoverished and debilitated, immigrants arrived in the state's expanding industrial cities from the Maritimes and Quebec. French-Canadians faced a similar, although less drastic agricultural crisis after mid-century, and began moving to Maine in large numbers in the 1870s, eager to trade the uncertainties of marginal farming for the security of a weekly paycheck.

Liverpool to Boston ship passage receipt, 1847

Maine Historical Society

In both cases entire families worked – the men as day laborers digging canals and foundations and railroad grades, and the women and children in the mills. Both groups lived in segregated neighborhoods, often on cheap land near the factories or warehouses, where crowding and sanitation problems brought outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. And, both groups were subject to nativist hostility.

In addition to these new textile cities, Portland expanded its industrial output in the first half of the century, based on its rapid population growth and profits from the West India trade. Ships carrying fish, produce, livestock, and box shooks to the Caribbean returned with sugar and molasses. Portland capitalized on this trade by building sugar refineries and rum distilleries.

The city's infrastructure was geared to the West India trade, but in the 1840s Portland lawyer John A. Poor helped the city diversify by promoting a rail link to Montreal, which became landlocked when the St. Lawrence froze over each winter.

Because Portland was 100 miles closer to Liverpool than was Boston, Portland enjoyed advantages in the transatlantic trade in Canadian timber, agricultural, and mining products. The Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railway was completed in 1854. The rising tide of Canadian staples stimulated development of wharves, piers, stockyards, grain elevators, coal facilities, warehouses, and shipyards, transforming Portland into a major western Atlantic shipping point.

Steel Co. of Canada Railroad locomotive #1, ca. 1876

Maine Historical Society

Beginning with these profitable enterprises, business leaders diversified into other forms of manufacturing, including, at one point, railroad locomotives. While no single enterprise was as spectacular as Lewiston's huge textile mills, Portland's smaller and more diversified industries made it the largest manufacturing center in the state.

John A. Poor's audacious railroad schemes – the Atlantic and St. Lawrence and later the European & North American Railway from Bangor to St. John – convinced many that Maine's development hinged on a mix of local resources, outside capital, and good transportation. At mid-century Maine's rail system was consolidated as the Maine Central Railroad, and in the 1890s the Bangor and Aroostook stretched this system into the productive potato and lumber region of eastern Aroostook County and the St. John Valley.

Transportation, capital, waterpower, and natural resources held great promise for Maine's Industrial Revolution, but there were also constraints: a labor force scattered through the upland farm towns and coastal villages or looking for new opportunities beyond the state's borders, and an economic and political system locked in the embrace of the old staple industries.

Still, Maine's prestige as the nation's supplier of fish, textiles, and construction materials gave its political representatives prominent standing in Washington as America approached a critical test of nationhood in 1861.