Maine was chained to an economic structure that saw its heyday in the 19th century.

Trends in farming helped shape the economic geography of the "Two Maines."

By the early 1980s Maine stood in the forefront of the nation's water pollution control effort, ready to pioneer other forms of environmental legislation.

In a 1945 address to the legislature, newly elected Governor Horace Hildreth vowed that postwar Maine would not return to a New-Deal "boondoggle." Nor would Maine seek "outside capital" as a means of resuming prewar production, since "the measuring stick ... for ... absentee ownership [is] ... not only how much money is put into Maine, but also ... how much money is taken out of Maine."

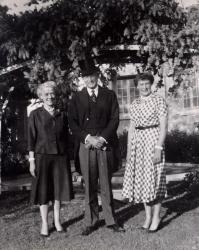

Senator Smith meets with Ambassador Horace Hildreth, 1955

Margaret Chase Smith Library

The typical Mainer, in his vision, would tend his own farm and work in a nearby mill, foundry, or factory. He would cultivate his independence, save his money, and perhaps start his own small business. This was the door to opportunity in Maine, and neither big government nor big corporations would be "allowed to close it."

Like many in this war-torn decade, Hildreth harked back to a simpler time when small-town, face-to-face relations insulated citizens from the nightmare of mass society and totalitarianism that darkened the previous years.

Insular in his thinking, Hildreth reflected a general nostalgia for things as they were, but for Maine, the past was more a burden than a sanctuary. America emerged from World War II with a booming economy, a new consumer-based society, and a future that promised unbounded prosperity.

Maine, on the other hand, was chained to an economic structure that saw its heyday in the 19th century. Its schools, hospitals, prisons, and insane asylums were antiquated; its tax system inequitable, and its roads out of repair. Forty years after the automobile revolution farmers still struggled through rivers of mud to reach their markets in springtime.

The years after Hildreth's speech brought mill closings, rising levels of water pollution, continued out-migration, and an "attitudinal slump" that reinforced the distressing cycles that made the transition to a modern economy all the more difficult. Nostalgia was no refuge for Maine; its future lay in closing the gap with the rest of the nation, hell-bent for the future.

Dairy trucks on parade in Portland, 1949

Maine Historical Society

Rural Maine at a Crossroads

Agricultural trends mirrored the gap between Maine and the nation. Wartime labor shortages and high commodity prices triggered a revolution in American agriculture, bringing new labor-saving machines; a new array of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides; and increased production through hybrid seeds, artificial insemination, hormone growth stimulants, and antibiotics.

Rural electrification modernized farm work and domestic life across the nation, while mechanization released farms from the constraints of labor supply and led to dramatic increases in size.

Farms in the more remote sections of Maine were too poor to make this transition. Burdened by poor roads, limited social services, and declining off-farm job prospects, families withdrew from the farm economy, often through a series of decisions: "I sold the cows when the barn floor collapsed, loaned out one horse when its mate died, sold the sheep when the fences got too weak, and now I rent the tillage land and have a town job."

For many, this train of events ended in out-migration, which compounded the poverty problem for those who stayed behind.

Cornfields, Fryeburg, ca. 1950

Maine Historical Society

In Aroostook County and in the central river valleys, farmers joined the agricultural revolution but found the postwar world a far more competitive place. Earlier, the federal government had launched a series of massive irrigation projects on the Columbia, Snake, Sacramento, Rio Grande, and Colorado river systems, bringing millions of acres of formerly arid lands into farm production, and the 1956 National Interstate and Defense Highways Act produced a highway system that allowed these new western growers to compete in eastern markets with minimal extra transport costs.

Maine farms followed national trends, albeit more modestly, in mechanization, specialization, and farm consolidation. The number of farms in Maine had peaked in 1880 at 64,000. By 1940 Maine had only 39,000 farms, and the figure dropped to 6,800 in 1975, while average farm size increased from 105 acres to 221 acres. These larger farms specialized in potatoes, dairy products, broiler chickens, and eggs, which together accounted for over 70 percent of Maine's total farm output.

Threshing peas, ca. 1955

Oakfield Historical Society

The Maine poultry industry exemplifies the uncertainties in these new trends. Since autos and trucks were replacing horses by the 1930s, Maine farmers no longer grew large amounts of hay, and they began using their barns to raise poultry.

During the war, chicken was one of the few meats not rationed, and in the postwar years demand for chicken continued upward. New York processors entered in the business, and by the 1950s these middlemen were supplying chicks, feed, litter, and medicine, and Maine farmers providing space and labor.

The number of facilities in Maine increased more than 1000 percent between 1945 and 1950, but in the early 1980s the broiler industry collapsed when producers south of New York entered the market with cheaper feed, energy, and transport costs and a vigorous advertising campaign. In Maine, revenue dropped from $93 million in 1979 to $53 million just two years later.