Cartoon supporting woman suffrage, ca. 1917

Maine Historical Society

A "Call for a meeting to discuss separation from Massachusetts in April 1816 is addressed to "influential gentlemen." Merchants and professionals favored statehood, perhaps with an eye toward the opportunities of power a new governing structure would bring. Despite the seeming importance of the drive for statehood, most Mainers were not interested in this issue with more pressing concerns of day to day living taking precedence.

One hundred years later, the fight for woman suffrage drew supporters and opponents whose differing perspectives on the proper role for women was captured in cartoons, speeches, and pamphlets.

Illustrating the complexity of history, dividing proponents and opponents of the vote strictly along gendered lines would be fruitless. The Men's Equal Suffrage League of Maine staunchly supported women's suffrage; the Maine Association Opposed to Suffrage for Women gained 2,000 new female members between 1913 and 1917. Gender alone cannot explain the breadth of opinions –– perspectives –– embedded in this debate.

Attention to perspective can reveal the tension between cultural ideals and reality. Take, for example, prohibition. Under the guidance of temperance leader Neal Dow, Maine became the first dry state, enacting prohibition in 1851.

Portland City Hall Rum Room, ca. 1930

Maine Historical Society

This law might suggest that all Mainers eschewed alcoholic beverages but historical evidence suggests otherwise. Photographs of rum rooms document copious quantities of confiscated alcohol.

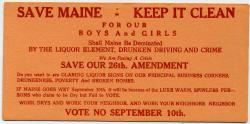

A satirical post card suggests the failure of temperance; an election card from 1911 reveals the fears of social collapse in face of alcohol use – a condemnation of ongoing, albeit illegal, behavior.

Even furniture confirms the business of selling booze, hidden in the secret compartment within a Victrola in one image.

The lesson for historians is to continue to question what would seem to be fact. Were all laws widely adhered to? When were they flaunted? By whom? In what circumstances? Why?

Prohibition election card, 1911

Maine Historical Society

Any proscribed behavior – laws, rules, etiquette – places before the public an ideal. But what was the reality? Historical evidence provides the clues and points the way toward perspective.

Considering diverse perspectives raises yet more questions. When faced with multiple versions of an event, which accounts will the historian trust and which will be discounted? Which point of view gets us closer to our goal of understanding the past?

Historical actors have their own perspective, but so do contemporary historians, like their subjects shaped by gender, class, ideology and other factors. What perspective does the historian bring to a project and how might that shape his or her own view of the past?

Uncovering evidence, placing it in a context and understanding the perspective of those behind the evidence provides the historian with the material to craft a story – the vehicle by which historians communicate history to a wide audience.

Narrative

History is built on stories that we tell each other and we tell ourselves. The stories we share form the core of our collective understanding of the past, our history. In books and magazines, on websites and blogs, on television and in cinema, historical stories engage us and shape our understanding of the world around us.

Parade of elephants in Lewiston, ca. 1900

Lewiston Public Library

Each community has tales to tell of the life and people that make that place home. Stories, both written and oral, form an important part of the historical record, but one that must be examined critically.

Stories shared generation to generation – our community memories – often reflect what we want to believe about the past, rather than what has actually happened in the past. This is narrative, a story critically examined that tells us both about past and present.

Historical stories often take on a life of their own. Stories are passed down generation to generation and like the child's game of "telephone" (itself a reference to an earlier technology where "party lines" made private conversations very public), information is often misheard or misremembered.

Some things are left out, other things are added in, an impulse that shapes a story to fit a particular purpose at a particular point in time. Stories, in other words, have their own dynamic life and the task of the historian is to assess critically any given tale.

A story about an elephant illustrates the point. In the early 19th century, the first elephants were brought to the United States. A curiosity, elephants were walked from town to town and residents were charged a fee for the opportunity to see this unfamiliar beast.

York County Courthouse, 1894

Alfred Historical Committee

One York County story makes the claim that the first elephant ever killed in the U.S. died in Alfred in 1816 – a victim of a farmer's anger over the sin of wasting money on frivolous entertainment. The farmer, so the story goes, followed the animal, named Old Bet, as the procession left town and shot it, killing the poor creature. The elephant, it is said, was buried on the spot (today, Route 4).

A herd of websites feature this story and every few years, a newspaper article recounts the elephant's fate. A local restaurant memorializes Old Bet with elephant knick knacks in its décor. Residents point to a small monument marking the location of the elephant grave.

Comparing multiple versions of Old Bet's story reveals variations in the admission price, the type of gun, and the motivation of the assassin. This story has been told since 1816, an indication that there is a lesson to be learned, something successive narrators have felt was important enough to share in the telling.

Last telephone cordboard, Bath, 1982

Maine Historical Society

So what does this narrative reveal? Is this a story about cruelty to animals? About Yankee frugality? A reflection of pious ancestors? About the need for gun control? Is this a story of civic pride or town shame?

Why, almost two centuries later, do we persist in remembering Old Bet? In telling this story today, how are we thinking about the past? Does this narrative reflect how similar we are today to our elephant-viewing ancestors, or does the story comment on how different we've become? In telling this story, what are we trying to say?

Our stories – in the form of oral history and written narratives – provide historians with dual sources of information: clues to the facts of the past, and, clues to what is important to tellers in the present.

Ida Skinner letter to brother, 1903

Maine Historical Society

Stories capture the passage of time and our reflections up on it. Photographs of the last telephone cordboard and the last hand-cranked phones, both images from 1982, document changes in communication technology in the 20th century.

Both photographs include in their titles recognition that these are the "last" indicating that from this point forward telephone technology and use will differ. Was this awareness greeted with joy or sadness?

Direct dial phones made communication easier, but the loss of cordboards (replaced by electronic technology) led to the loss of jobs. In 1903, Ida Skinner assured a visiting brother that she and a friend both had telephones and found them "very convenient."

From hand cranked, to handheld, to hands free – the changing technology of telephones tells a story of the passage of time and our keen awareness of those fleet years, a recognition that often takes shape as nostalgia. These stories, imbued with emotion, make particularly potent narratives that document, and comment upon, change over time.