Memory

Our most treasured stories form a collective memory, an agreed upon corpus of tales that define and describe us as a people, a community, a state or a nation. We need look no further than our early schooling to identify our shared national identity built from stories of the Mayflower and first Thanksgiving, of George Washington's bravery, of Benjamin Franklin's ingenuity, and of Lincoln's moral courage.

Americanization class, Boys Club, Portland, 1923

Maine Historical Society/MaineToday Media

Becoming American is in part learning the national memories, as this photograph of young immigrant children depicts. Traditional celebrations express these same commonly held beliefs as participants remember whatever is defined as "our" history in parades, festivals and community gatherings.

Old Home Days across Maine emphasize the connection between the community of "old" and the community of the present by way of shared memories.

Yet memory is not static and each generation selects the incidents and stories that best define their community at that moment. In 1850, for example, the death of a mill girl made newspaper headlines and spurred the publication of two short novels on the victim's life and tragic death.

Hundreds attended the trial for her murder and eager visitors flocked to visit the site where her body was discovered. Editorials bemoaned the loss of a poor, friendless young woman, a consequence, in part, of the rapid growth and industrialization of Saco.

Such essays voiced the nostalgia-tinged recognition that the small, familiar farm-based community of the past was no more.

Cover, 'Mary Bean or the Mysterious Murder,' 1851

New Hampshire Historical Society

Sixty years later, in 1913, Saco historian John Haley included a brief recounting of this same event in his town history but offered a version filled with erroneous additions and factual omissions. From Haley's less sympathetic perspective, the unseemly story he believed to be true should be "consigned to dust and d---d oblivion," a tale no longer worth telling for the poor light it shed on mid-19th-century Saco.

By the end of the 20th century, the event that at one time captivated a community and beyond, had disappeared from Saco history. What was shocking, unfortunate, or unsavory to past generations – and worthy of memory – had become commonplace and familiar and not worthy of remark.

Memory helps individuals and communities negotiate between the past and the present in a continual process of building a history. What we choose to remember and what we choose to forget is part of the continual construction of our collected memories.

Memories are not so much reproduced verbatim generation to generation as they are constructed; selected and agreed upon by a community, small or large, for the lessons they impart and the values they illustrate.

In crafting their stories, historians grapple with the dynamic interplay between nostalgia and evidence and narrative and perspective as they translate memory into history.

Historians Over Time

Examining change over time is an important facet of historical research. It is important to recognize that historians' concerns, methods, approaches and styles of telling history also change over time. Because historical writing often reflects the times in which it was created – politically, socially and culturally – histories written a century apart about the same event are often strikingly different.

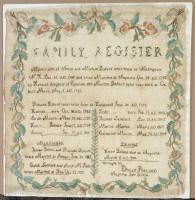

Family Register stitched by Dolly Pollard, 1820

Maine Historical Society

The history of Hallowell presents an example. Historians in the early 20th century had access to the diary of 18th-century mid-wife Martha Ballard but saw in its brief entries only minutiae of daily life and concluded there was little in there worth including in a town history.

Decades later, historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich read that same diary and, with considerable painstaking research, teased out of ordinary entries an extraordinary life. Ulrich's insights and new approach to an already examined document reflected historians' new interest in women's lives, stimulated by the late 20th-century women's movement.

In turn, Ulrich's study, the Pulitzer Prize-winning book A Mid-wife's Tale, inspired other historians to examine more closely, instead of dismissing, the diaries of those leading quieter lives.