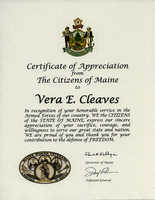

A story by Vera Cleaves from 1940s

Vera Cleaves (1914-2017) was one of the first to join the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) during World War II in 1943, saying, “Everybody was joining up and doing their bit and I wanted to do mine. I thought maybe I could do something, and wanted to help.

“I had a mechanical background, I’d watch my dad repair his machines, and that background helped a lot in the Army. I had been with American Red Cross Boston chapter as an ambulance driver and I had worked for John Hancock in the actuary department for 6.5 years before enlisting.

“At basic training in Florida, I taught drills and marching to 6500 girls. Tough way to live, but I enjoyed it. I was an outdoor person and athletic. I spent my life doing physical education, camping, I was in the campfire girls and scouting, and worked as a camp counselor. My family camped down to Westport, in New Hampshire, and climbed Mt. Washington when we were growing up. The Army wasn’t so much an adjustment for me, but for some of those girls it sure was.

“I was picked with another girl out of basic to go to the Point, they weren’t crazy about having girls--women. I wanted to stay in Florida, and the girls wanted me there, but the powers that be in West Point, when they say they want something they get it.

“The Army sent us beautiful uniforms because we were going to the Point, but I thought that was dumb. Whether I thought that or not, they did. We went up by train, and had our own private car and sleeping car, which I wasn’t used to but nevertheless adjusted to!”

Recognized for her teaching aptitude and mechanical skills, Vera was one of 124 WACS stationed at Stewart Field in Newburgh, New York, the Wings of West Point. “The Point was fussy having women there. Really, I don’t think they wanted us there, but after a while we all adjusted.”

“They put me in women’s drill and I taught gym to the women at West Point. I wasn’t sure of it, but I was trained in Phys Ed, having finished two years through a scholarship at Boston College.

“The female officers wanted to have gym by themselves, they didn’t want to be with the enlisted girls. That made me sick, but I couldn’t do anything about it. They were nice officers, however, and they were good to me. This is mean, but I loved making them squawk. I thought they’d made the kids squawk, so I’d make them squawk!

“There’s nothing good about the weather up there. I had the girls fall out whether there was snow on the ground or 10 degrees below zero, no difference. One morning I had them lined up and it was snowing, and there was a car out front, and I knew it was one of the chiefs, so I had the girls fall out, high on the hill, it was snowing, and cold! And of course, the girls wore shorts and knee socks for uniforms, and there was about a foot of snow on the ground and I thought, I’m going to have them out there to show the officers how tough we are. So, they fell out and the officer car came driving up and it was black, the field officer. There must have been four officers in there, and they slowly drove by us, as slow as can be, and looked, and I was so mad, and the minute they got past us I didn’t give any more exercises, I shipped the girls inside. We had some nice officers at the Point, but nice in so far as you obeyed their command.

“I learned to fly; I had a tough time getting away from teaching gym, they didn’t have anybody else to do it, but an officer down the link said he needed a flight instructor, so I got to pull strings. Nine of us women learned to fly. We had to have 90 hours of flying time in a month, the officers did too, so if they weren’t busy or we weren’t busy we’d take off in a plane. One time we stopped in Hartford for supper, and when we came home the moon was out so we flew down to Georgia.

"The WACs taught instrument flying on the ground to the male West Point cadets. They came to us for 6 months or so, they came as youngsters, students. We’d put the cadets into AT-6 trainers and give them a pattern to fly. We’d give them commands like, fly up 50 feet and go down and land—we had regular lesson plans. Later, when the training lessons were finished, an officer upstairs would take the cadets and they’d do the same thing in an airplane. They were gems, let me tell you. The cream of our society.

“I met Ike (Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower), his brother was made president of West Point, so I attended the inauguration and I shook Ike’s hand quite a bit. He was a nice guy, and very calm. During graduation, the war was on, and West Point was short on officers to participate. They asked me, and I got to stand up on the stage and give out degrees to the cadets. That was quite a sight, when they throw those hats up, that was something to see!

“We were pretty much stuck on the Point all the time. I told the girls if we found an old car, I’d repair it, go over it and all, and we could go away weekends. We were tied down night and day, but after a long search, we found a car--full of junk and the windows knocked out, it was a ‘29 Ford. The man wanted $100 or $150 for it, six of us girls chipped in to buy it. In fact, he didn’t want to sell it because he thought it was too bad. I took it up behind the dormitory where the girls were staying on the Point—which you weren’t supposed to do--When we got 5 minutes off, which wasn’t very often, we’d repair it. I talked with one of the mechanics where they repaired the planes. He was a father and had a son in the service, he was a nice man and he agreed to help us if we had any problem with the Ford. The fellows knew what we were doing, and they named the car, the Hornet, and we had it painted Kelly green, with black sateen seat covers. We used it for weekends when we had any time off to go up to New Hampshire and stayed in a farm house. We did that half a dozen times, anything to get away from that pressure, because we were under terrific pressure.

"I left the Point and I went to college in Pennsylvania. The war was over, I was 28 or 29 and all the students were young fellas, and I was with all fellows because of my background. They accepted me because I was older. I was a mama hen, and they were wild! A lot of the men were straight off the battlefield. I went into teaching, became a principal, and an assistant college professor.

“I’d do it again, if they asked and if I was young enough, of course.”

Vera Cleaves with her grandfather, Westport Island, 1922

Item Contributed by

Westport Island History Committee

Vera Cleaves, Women's Army Corps, West Point, New York, 1943

Item Contributed by

Westport Island History Committee

Friendly URL: https://www.mainememory.net/mymainestory/veracleaves