A story by Ted Heselton from 1967-1968

I was raised in Skowhegan and went to high school there from 1962-66. My Dad was an Army sergeant in World War II and spent a couple of years building roads and airfields in Okinawa and Saipan. By the mid-1950s, I was going with him to Civil Defense meetings as he was instrumental in that organization. As a boy of seven or eight, I heard about the threat of Communism in the basement of the Somerset County Courthouse from those veterans of World War II.

I joined the Army in September of 1967 “to avoid the draft” as the saying went at that time. I wanted to get trained as a heavy equipment operator to be able to get a job after discharge. After basic training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina and eight weeks of school in Missouri, I flew to Vietnam in February of 1968. When we landed at Ton Son Nut Air Base there were prop-driven planes, Sky Raiders, dropping bombs about 200 yards away to suppress rocket fire on the airport. The drive through Bien Hoa was like a WWII scene with sections of town bombed almost flat.

My first job was working on the defense perimeter at Long Binh, a big and quite safe base north of Saigon. Every fourth night, I was on guard duty there and it was pretty boring. Within a couple of months, we were traveling west to a First Infantry base called Dian to work on roads and the defensive perimeter there. Two men in my company were killed when they drove over a mine intended for a tank or armored personnel carrier. I started to get concerned as I was driving those same roads. The Viet Cong (V.C.) had blown up a bridge outside of Dian during the Tet offensive, so we went to see what was involved in rebuilding it. Our guys at the bridge site had no security, so four other guys and I got our chance to play “real soldier.” I walked point toward the Saigon River. I had been told the V.C. would hide sampans (think small canoes) in holes in the riverbank and run weapons and explosives up and down the river at night. When I got to the top of the riverbank, a couple of AK-47s opened up on me. I couldn’t see a muzzle flash, much less a V.C. to shoot back at, so I dove behind a paddy dike. Rounds hitting the top of the dike kept me right there. My friends were lying in a ditch and on one was shooting at them. The firing stopped and I ran to a strip of jungle to work my way back to where they were. We took sniper fire the rest of the days were were out there, but it got routine because it wasn’t accurate.

Seven or eight months into my 12-month tour, I was sent to BearCat—a base at Tri-Corners northeast of Saigon—where I spent the rest of my tour. I drove a Cat D7E bulldozer to push the jungle back from the base, as well as a low bed tractor-trailer to haul the dozer other places. The defensive perimeter at BearCat consisted of three coils of razor wire (one stacked on two) with another three coils about 30 yards out. Days were spent driving “engr. stakes” (think metal signpost uprights) through the razor wire and then short stakes to hold the “Tangle foot” barbed wire run about a foot off the ground, randomly. These short stakes would have trip flared tied to them and we’d run monofilament line from trip flares to the stakes. The idea was if the V.C. got through the outer ring of wire, they would trip a flare running to the inner perimeter wire. Those of us who slept “behind the wire” (on the base) at night felt, at times “less than” Army infantry and Marines. That was a common feeling among support troops.

We were attacked two times at BearCat, one daytime ambush on the road just outside the perimeter and one nighttime attack about 3:00 in the morning. Another soldier and I drove through the ambush just before it was sprung. In the nighttime attack, I shot someone for the first and only time. I’ve often wondered if that guy made it—I’ll never know because there were no bodies there in the morning. Another time we woke up with rounds coming through our tent at 2:00 or 3:00 a.m., just a foot or so above our heads. I had assumed the V.C. had gotten into our camp, but it was a guy from our company, drunk with an AK-47. Our captain talked him down and got the gun. I got one more chance to walk point at the end of my tour. Along with three other guys, I took a security patrol out through a rubber plantation just outside BearCat to protect other engineers working on the perimeter.

I have thought about Vietnam almost every day for 48 years. I spent a couple of months back there in 1990, but that is another story. When I see an old gray haired veteran with a Vietnam Vet hat on, I always say “welcome home”, knowing that man or woman may have waited almost 50 years to hear that.

To sum it all up, Vietnam broke my heart. The war killed my friend, Bill Breece, wounded my friend Pete Jewell. It killed Alan Ward, Terry Corson and Dave Bosworth, with whom I went to high school. I still see the sign outside an orphanage near BearCat which warned, “Don’t Shoot Toward the Orphanage”. It was full of bullet holes.

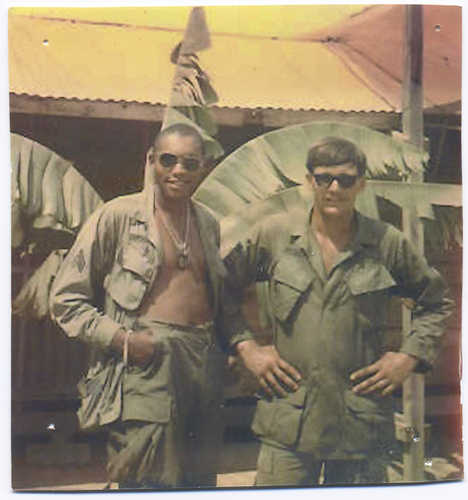

Ted Heselton (right) with two fellow soldiers in Vietnam, 1968. The man in the back holds a peace sign and the African American man is giving the "power sign" with a clenched fist. To me both represent that the guys that went to Vietnam were a reflection of the society in 1968: Civil Rights and the Peace Movement.